DARING DUELS OF THE WALL RIDERS

J. L. BEARDSLEY

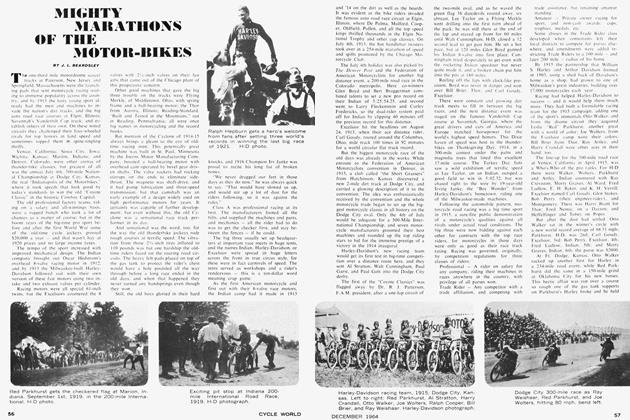

ANYBODY LOOKING for real speed thrills in the years before World War I automatically had to be a motorcycle fan. The motor bikes were going faster than their four-wheeled rivals in motorsport by then, and it took the 45-degree banks of motordrome board bowls to hold them between the fences.

While the autos ran at long intervals in dusty road races, the two-wheel speed addicts in dozens of cities could always hop a trolley to a motordrome in the suburbs and see a weekend afternoon of split-second finishes at 90 miles an hour as the daredevils rode the walls wheel-to-wheel. It only cost fifty cents to see the thunderbikes go with celebrated speed stars in the saddle — never did so much cost so little.

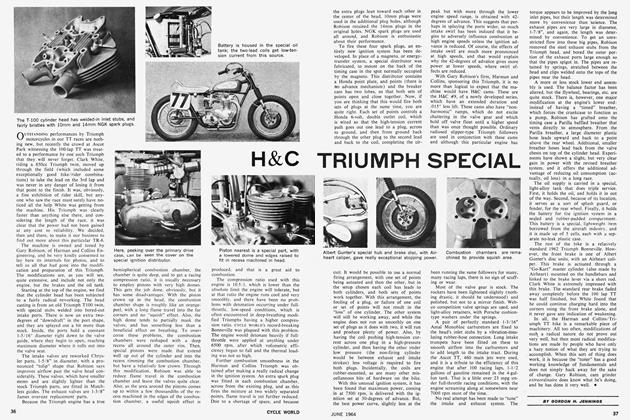

The architect of the quarter and onethird mile motordromes was Jack Prince, a New Jersey engineer who eventually built a chain of them from coast to coast, where the Indians, Flying Merkels, Thors, Excelsiors, Cyclones, and a lot of other bikes that could really go, blasted spectators' eardrums with their open-port motors in that long gone day when a new sport was born. The first of the Prince promotions was the Velodrome, a one-sixth mile saucer banked 48 degrees, built at Paterson, New Jersey. It opened in July 1908, and was an instant success with match events and record attempts. Here the great Indian speedster, Jake De Rosier, began to build a reputation for the red machines from Springfield with sensational speed on the Velodrome banks. His first record was a 56 second mile, four seconds under the then existing mark.

From this day on, the bikes had a big time sport going on their own special tracks. It was great publicity for the manufacturers, and great sport for the fans while it lasted. In a little over two years the motordrome circuit spanned the country. The swiftest sport on wheels drew upwards of 10,000 weekly in the larger cities, where hometown stars were pitted against nationally known riders. Rivalries developed, and newspaper publicity helped build followings for some riders as partisan as any fans of pro sport heroes today.

Jake De Rosier, ace of the Indian race team and motorcycling's first National Champ, went west in 1909 to defend his records made on the Velodrome, boards on a new one-third mile drome, the Los Angeles Coliseum's, completed early that year by Jack Prince. Here he tangled with the coast champ, Paul Derkum, on a ReadingStandard machine; Art Mitchell, on an N.S.U.; Will Samuelson, Indian; Fred Huyck, Indian; and Ligenfelder, on a Thor.

But the torrid Frenchman was too hot for the boys who had been thrilling the crowds at the 63rd and Main bike speed palace, and De Rosier lowered the world mark to 47-1/5 seconds, and all others up to 20 miles. Even with the small tanks of his strictly sprint machine, he set a 100-mile record of 97 minutes with several fueling stops. De Rosier returned home to appear at the opening of the new Springfield Stadium track in which the Indian company had an interest and the California handlebar experts lost no time in chopping away his records. Morty Graves, one of the real pros, on a Flying Merkel, starred in a 6 hour enduro at the Coliseum run in 2 hour heats on successive days in July 1909. Changing machines each day he completed 100 miles on the last leg in 87 minutes for a new record.

The record attempts were added attractions to regular race cards, and in one, Ray Seymour, a rising drome jockey, lowered the mile to 47 seconds flat on a Reading-Standard; while Ligenfelder's Thor ¡ was good for a 15 and 25 mile mark. Back in Springfield, Mass., though, Jake De Rosier sent his Indian three times around the Stadium's 48-degree banks in what newsmen called "a blur of red," for a new mile in 42-2/5 seconds, and was king of the boards once more. The Indians were born on the board dromes and had grabbed the limelight through Jake De Rosier's sensational riding — but there were other good reasons. Oscar Hedstrom's new carburetor, and his steady engineering improvements gave them an edge over the products of the 44 companies that sprang up in the motorcycle game by 1912. Speed on the dirt tracks, road races, and the spectacular dromes, was the magic that sold motorcycles in the pre-World War I years; and the red flyers from Springfield had their troubles holding off the challenges of such well-built and fast machines as: Excelsior, Harley-Davidson, Thor, Reading-Standard, Pope, Flying Merkel, Emblem, and Cyclone, though Harley never supported the drome sport.

In 1910, another great speed arena went up at Venice, California (near Los Angeles), the Playa Del Rey, a pine temple of thrills a full mile around and banked for use by motorcycles and autos, and a dream track for the handlebar pushers. De Rosier was there for the opening with his 61-inch twin to see what he could do on a big circuit where the sky was the limit. In an attempt to regain the 100-mile mark, he reeled off the first 50 in a record 39:13, and had Graves' standard beat by a full five minutes when he completed his 99th lap and then suddenly ran out of gas; but with a game push-in finish he managed to clip the old mark fractionally to 1:26.14.

The dromes were catching on fast in the west. The next to open was the Wandemere in Salt Lake City, in the summer of 1910. This was another three-laps-to-themile track which was about standard, and the banking was 45 to 48 degrees. The best locations were in or near amusement parks. De Rosier showed up for the Wandemere opening, going against such hot handlebar demons as Ray Seymour, Morty Graves, AÍ Ward, and Charley "Fearless" Balke, to some near-photo finishes. F. E. Whittler, a local star, really stole the show on his Flying Merkel by beating De Rosier's records from 17 to 35 miles, when his motor overheated. Another Flying Merkel jockey, Morty Graves, knocked off still more from 2 to 20 miles, including four of Whittler's on the same day, and the Salt Lake bike fans went home with plenty to talk about.

De Rosier, and other star riders, were much in demand as the motordrome circuit expanded, but De Rosier was back on the coast for the winter races and immediately took back all the records he'd lost, from a 42-second mile all the way 35 miles at the Los Angeles Motordrome. Then on the last day of 1910, "Fearless" Balke wound up his Excelsior on this big saucer and ran off with the best times from 2 to 20 miles..

In 1911, the Federation of American Motorcyclists re-classified all the amateur riders as pros to improve competition and simplify regulations. Every rider could now share in the purses and salaries if he was good enough to land on a factorysponsored racing team — or he could have a lot of fun trying. From a competitive standpoint the big news was Indian's new racing engine with 8 overhead, push-rod operated valves per cylinder, that was going to be hard to beat. Belt drive had become obsolete, and the trend was to "freeengine" clutches and two-speed transmission, for the motorcycle was growing up to become a more complete and exciting sports machine by 1912.

This was only part of the fascinating hobby for non-riders who flocked to the motordromes for their share of thrills by the thousands every week, reveling in the roar of open exhausts, burning castor oil fumes, and the daredevils who rode the walls. As a spectator sport the motordromes soared to new heights and a gi-*" gantic drome circuit soon spanned the nation from Atlantic to Pacific, and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf. Two-wheeled thrills were sold on the boards in Milwaukee, Chicago, St. Louis, Omaha and Houston; in Cleveland, Buffalo, Detroit, and Indianapolis; and there were roaring bowls in Philadelphia, Newark, and Atlantic City. In addition to those mentioned there was Denver with two in operation, the Tuileries Park and Lakeside, and Los Angeles now had three going. But the biggest, and probably the fastest of all the regular dromes was the Elmhurst in Oakland, California, a full half-mile saucer where world record speeds were made, and spectacular match races between autos, and even airplanes, were sights never seen before on the bike bowls.

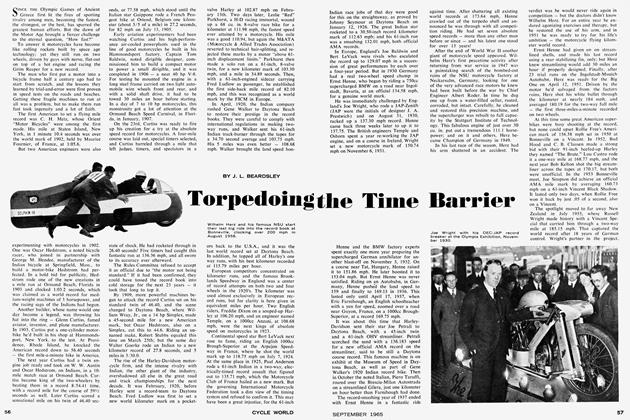

The Chicago-built Excelsiors countered Indian's 8-valve race motor with a big 2-1/4-inch valve package of dynamite of their own. Joe Wolters gunned one of these Big X jobs around the Riverview Exposition track, in Chicago, for a new drome record of 89 mph, on a six-lap track, a feat that packed the Windy City plant for a $60,000 box office take in the next six weeks. The Indian ace, De Rosier, was on a European tour, so the first of the new 8-valve race motors from the Indian factory went to Ray Seymour and Eddie Hasha. Immediately, Hasha rewarded his bosses with a world mile drome record of 39-3/5 seconds, and later boosted it to a 95-mile-an-hour clip on the Playa Del Rey saucer. On May 17, 1912, Ray Seymour topped this one on the same track with 98 mph.

The expanding motorcycle market that saw Indian sales reach 19,500 in 1912, was a prize all manufacturers fought hard to win, and the ever-mounting speed index as riders went all-out to win added to the perils of the sport. The hotter bikes and mounting pace made headlines in the sport pages, but they weren't all good ones.

Glen "Slivers" Boyd won his nickname the hard way when a tire blew and locked his rear wheel, spinning him to the bottom of the Omaha drome. It took the doctors two weeks to find all the slivers in his anatomy, and one in his thigh was 14 inches long. This he carried with him for months afterwards to prove his story when some skeptic questioned it.

In 1912, Excelsior had specially tuned one of their 61-inch, open-ported, bigvalve twins into a real bomb, and they already had the right man to ride it — Lee Humiston. They fired this combination at the mile world record on December 30, 1912, at Playa Del Rey, and Humiston scorched the big saucer for a 36-second mile — the first 100 mph ever done on two wheels on a circular track. He screamed on for an even dozen world marks before his motor overheated.

But let's go back to 1911 for a moment. What kind of sport awaited the motorcycle speed fans in that long ago year? There was none better than the weekly fare dished up at the Elmhurst half-miler in Oakland, California. Three world's records were smashed at the opening program there November 12, 1911, and close to 8000 rabid speed addicts flocked there.

A capacity crowd was on edge for the entire 2-hour opening day speed festival, and pandemonium broke loose as nationally famous star riders mounted on the latest creations of the racing divisions of the big factories thundered around the oval in some hair-raising duels. This date amounted to a re-opening at Oakland, for Jack Prince had built the Elmhurst speedway early in 1911, but constant rainouts prevented his scheduled opening throughout April and May; so Prince moved to Chicago where he set up another tremendously popular drome that was soon packing them in to the tune of 10,000 a week.

"I doubt very much if an afternoon of sport the equal of this third meet has ever been witnessed," wrote J. A. Houlihan, reporting the November 27th card on the Oakland. Tribune sports page. It was opened by the sensational grudge match between Excelsior star, "Fearless" Balke and the Indian camp favorite, Ray Seymour, which was decided only in the last quarter-mile when Seymour shot a few feet ahead at the finish line.

Sports editor Houlihan should have saved his enthusiasm for later weeks, however, for Jack Prince promoted the greatest thrills ever seen on any motordrome anywhere. In 1911, when an airplane in the air was the eighth wonder of the world, Prince contracted with Jay Cooke, a local birdman, to fly over the Oakland drome, and in low circles he sometimes raced the speeding cycles below — a thrill circus unparalleled anywhere at that time. On December 4th, the ultimate in motor thrills was reached when Cooke put on a match race with Earl Cooper, in his famous Stutz race car, on the Elmhurst oval and Cooper was the winner. Novelties of this magnitude could not be presented on the smaller dromes of less than a half-mile and usually located in populous city suburbs, so the Oakland, California fans were the luckiest of all the motordrome followers to have witnessed these unforgettable super-thrills.

The great upheaval of World War I ended forever the motordrome's colorful era. After it was over the big road races, board speedway and dirt track meets, and hillclimbs took over and have developed American motorcycles to a high performance level over the years; but the old Motordromes gave them a good, fast, rolling start, and did improve the breed.