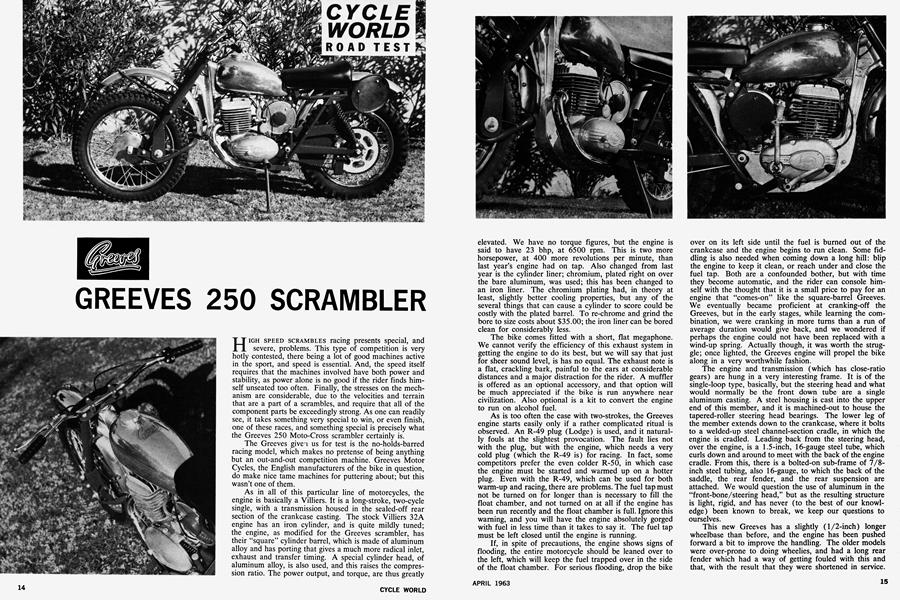

GREEVES 250 SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

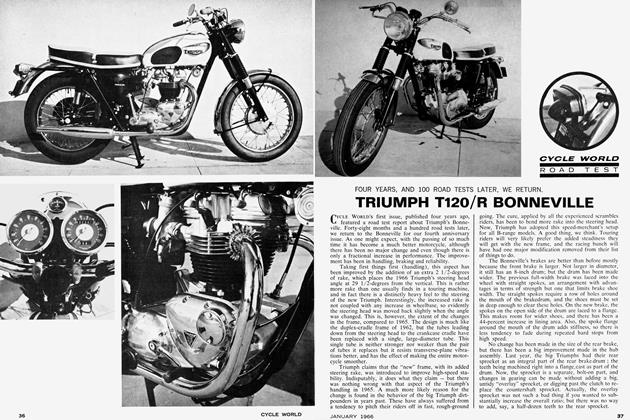

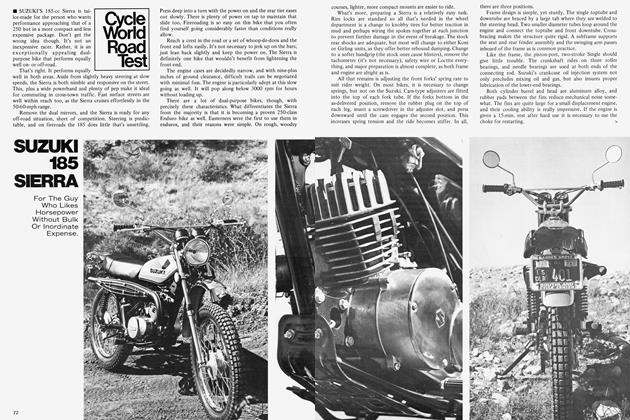

HIGH SPEED SCRAMBLES racing presents special, and severe, problems. This type of competition is very hotly contested, there being a lot of good machines active in the sport, and speed is essential. And, the speed itself requires that the machines involved have both power and stability, as power alone is no good if the rider finds himself unseated too often. Finally, the stresses on the mechanism are considerable, due to the velocities and terrain that are a part of a scrambles, and require that all of the component parts be exceedingly strong. As one can readily see, it takes something very special to win, or even finish, one of these races, and something special is precisely what the Greeves 250 Moto-Cross scrambler certainly is.

The Greeves given us for test is the no-holds-barred racing model, which makes no pretense of being anything but an out-and-out competition machine. Greeves Motor Cycles, the English manufacturers of the bike in question, do make nice tame machines for puttering about; but this wasn’t one of them.

As in all of this particular line of motorcycles, the engine is basically a Villiers. It is a long-stroke, two-cycle single, with a transmission housed in the sealed-off rear section of the crankcase casting. The stock Villiers 32A engine has an iron cylinder, and is quite mildly tuned; the engine, as modified for the Greeves scrambler, has their “square” cylinder barrel, which is made of aluminum alloy and has porting that gives a much more radical inlet, exhaust and transfer timing. A special cylinder head, of aluminum alloy, is also used, and this raises the compression ratio. The power output, and torque, are thus greatly elevated. We have no torque figures, but the engine is said to have 23 bhp, at 6500 rpm. This is two more horsepower, at 400 more revolutions per minute, than last year's engine had on tap. Also changed from last year is the cylinder liner; chromium, plated right on over the bare aluminum, was used; this has been changed to an iron liner. The chromium plating had, in theory at least, slightly better cooling properties, but any of the several things that can cause a cylinder to store could be costly with the plated barrel. To re-chrome and grind the bore to size costs about $35.00; the iron liner can be bored clean for considerably less.

The bike comes fitted with a short, flat megaphone. We cannot verify the efficiency of this exhaust system in getting the engine to do its best, but we will say that just for sheer sound level, is has no equal. The exhaust note is a fiat, crackling bark, painful to the ears at considerable distances and a major distraction for the rider. A muffler is offered as an optional accessory, and that option will be much appreciated if the bike is run anywhere near civilization. Also optional is a kit to convert the engine to run on alcohol fuel.

As is too often the case with two-strokes, the Greeves engine starts easily only if a rather complicated ritual is observed. An R-49 plug (Lodge) is used, and it natural ly fouls at the slightest provocation. The fault lies not with the plug, but with the engine, which needs a very cold plug (which the R-49 is) for racing. In fact, some competitors prefer the even colder R-50, in which case the engine must be started and warmed up on a hotter plug. Even with the R-49, which can be used for both warm-up and racing, there are problems. The fuel tap must not be turned on for longer than is necessary to fill the float chamber, and not turned on at all if the engine has been run recently and the float chamber is full. Ignore this warning, and you will have the engine absolutely gorged with fuel in less time than it takes to say it. The fuel tap must be left closed until the engine is running.

If, in spite of precautions, the engine shows signs of flooding, the entire motorcycle should be leaned over to the left, which will keep the fuel trapped over in the side of the float chamber. For serious flooding, drop the bike

over on its left side until the fuel is burned out of the crankcase and the engine begins to run clean. Some fid dling is also needed when coming down a long hill: blip the engine to keep it clean, or reach under and close the fuel tap. Both are a confounded bother, but with time they become automatic, and the rider can console him self with the thought that it is a small price to pay for an engine that "comes-on" like the square-barrel Greeves. We eventually became proficient at cranking-off the Greeves, but in the early stages, while learning the com bination, we were cranking in more turns than a run of average duration would give back, and we wondered if perhaps the engine could not have been replaced with a wind-up spring. Actually though, it was worth the strug gle; once lighted, the Greeves engine will propel the bike along in a very worthwhile fashion.

The engine and transmission (which has close-ratio gears) are hung in a very interesting frame. It is of the single-loop type, basically, but the steering head and what would normally be the front down tube are a single aluminum casting. A steel housing is cast into the upper end of this member, and it is machined-out to house the tapered-roller steering head bearings. The lower leg of the member extends down to the crankcase, where it bolts to a welded-up steel channel-section cradle, in which the engine is cradled. Leading back from the steering head, over the engine, is a 1.5-inch, 16-gauge steel tube, which curls down and around to meet with the back of the engine cradle. From this, there is a bolted-on sub-frame of 7/8inch steel tubing, also 16-gauge, to which the back of the saddle, the rear fender, and the rear suspension are attached. We would question the use of aluminum in the "front-bone/steering head," but as the resulting structure is light, rigid, and has never (to the best of our knowl edge) been known to break, we keep our questions to ourselves.

This new Greeves has a slightly (1/2-inch) longer wheelbase than before, and the engine has been pushed forward a bit to improve the handling. The older models were over-prone to doing wheelies, and had a long rear fender which had a way of getting fouled with this and that, with the result that they were shortened in service.

The new ones have the fender shortened, as delivered, and are mounted on a repositioned fender loop. The chain guard has also been modified. It is now open on the outer side, while still being closed next to the wheel; chain repairs are easier and the chain is still protected against the shower of debris from the rear wheel.

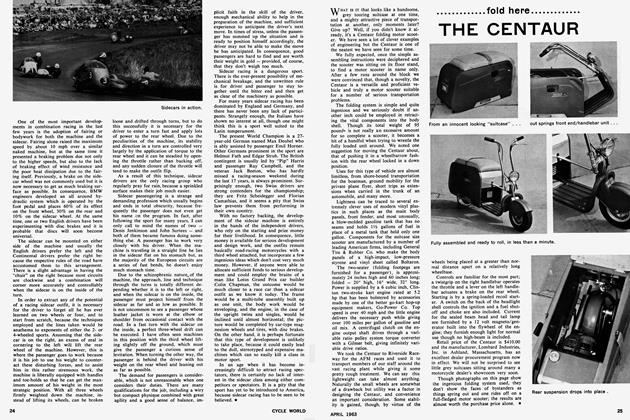

Among other improvements are a re-designed front fork. As those of you who have ridden Greeves will know, the leading-link front end on these machines has a tendency to yaw back and forth — a peculiarity that has not been known to un-seat anyone, but is a trifle unsettling for the rider nevertheless. The latest model has braces added around the housings for the rubber bushings that provide the springing action (by twisting) to improve lateral rigidity. And, the bracing loop is now larger in diameter. The new set-up is better, but that yawing is still there at anything over 45 mph. We suspect that some sort of steering damper — one that would not effect lowspeed control — might be a cure; and then again it might not. With or without the yawing, the Greeves has exceptional handling.

The Greeves brakes are good, as before, but conventional-pattern, full-width drums are used in place of the odd-looking petaled drums of the earlier model. The front backing plate has, of all things, a couple of cooling scoops, which we presume to be for the benefit of the road-racing version of this bike, the Silverstone.

Plastic-fiber air cleaner elements were used last year; Fram paper filters, in a new housing, are used for the new model. The carburetor draws its air from a chamber that, in turn, is connected to the side-mounted air-cleaner body. The new set-up does not appear to pick up quite so much of the dust raised by the machine, and the intermediate chamber prevents carburetor back-firing from fouling the air-cleaner element.

As before, the Greeves scrambler is a rider’s delight. The seat, pegs and handlebars are located perfectly, and if you can’t get the most out of the machine, it won’t be because you can’t get comfortably situated on it. Power is provided, almost to excess, and it has a broad-range torque that is a real blessing when things get sticky. The suspension will absorb almost anything without bottoming and the machine as a whole is enormously sturdy — and still manages to be light.

Perhaps one man’s experiences with the Greeves give the best indication of what it can do. Gary Conrad, one of Southern California’s most able sportsman competitors, bought a square-barrel Greeves from Nicholson Motors, the distributors, and went racing. He faced the starter 65 times, won 25 races, placed second 26 times, was third 8 times, and finished lower than third only five times. The single failure to finish a race was due to a broken chain. Friends, that Greeves is a pretty good motorcycle. •

GREEVES

250 SCRAMBLER

$795.00,

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue