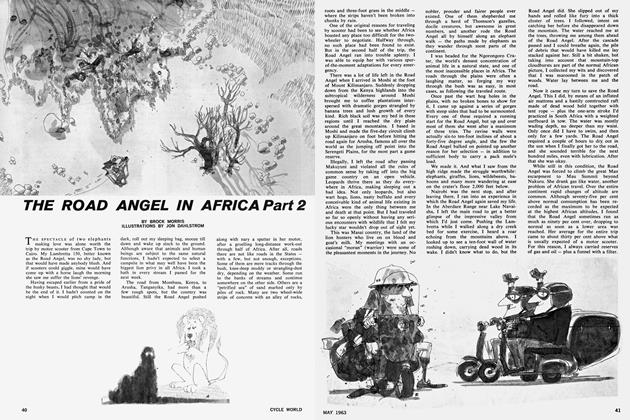

THE ROAD ANGEL IN AFRICA

Part 1

BROCK MORRIS

ROUNDING A BEND on my Lambretta 150, I came face to face with a pride of twelve African lions - only one of the many occasions on which I was to recall a Dutch sea captain's words: "A motor scooter trip through Africa may sound like fun, but if you make it alive, I'll swim around this ship naked. You're a damn fool!" (Happily, this particular fool lived to see that captain paddling nude in Hong Kong harbor sometime later.)

There were a lot of things I could have done when those lions caught sight of me - such as have a heart attack. As it was, I did nothing. No acceleration -that would have attracted extra attention.

No stopping - there was no use asking for it. I kept on going at the same speed, 20 mph - not more than three yards from the hefty, blacked-maned leader. Maybe he licked his chops, but this "blue plate special" got away, although a cousin of his got even with me later on.

From that day forward, my Lambretta and I were the best buddies ever. And in honor of the occasion when the twowheeler saved my life the first time, I called her the Road Angel.

Was I a fool to ride the Road Angel from Cape Town to Cairo, through some of the roughest and most dangerous coun try in the world? Maybe so. Was I an ass to travel 10,000 miles through wild game territory without a gun? You betcha! But after looking back at a few of the diffi culties - among them customs problems, high-priced gasoline (as much as $5 per quart), and visa barriers - I would do it again exactly the same way.

I was luckier than the newlywed couple I toasted with champagne in South Africa

before they got underway on a motorcycle for a honeymoon trip to Mount Kiliman jaro. Their graves were the first thing I was taken to see when I reached Iringa, Tanganyika. And then there were the three cyclists who got lost in the middle of the Sahara. News travels fast in Africa, but the telegraph and jungle drums never carried news of their rescue.

Once a fleet of ten motorcycles swept by me on the road north from Victoria Falls, headed for the Congo. Two Swiss boys scootering to Europe via the Western Sahara shared my mosquito net in the Mountains of the Moon. They made it. Others didn't, but the world's largest desert had already been crossed success fully by two-wheelers at least fifteen times in its western section. To my knowledge, I was the first and only to two-wheel the eastern extremity, known for a good reason as the Great Eastern Emptiness.

Why did I choose a motor scooter? To begin wth, I'd had a couple for knocking around Europe and the States. I knew what kind of performance I could rely on. Also, I had learned that when you’re on a two-wheeler, you don’t just see the landscape from under windshield glass; you’re part of it. Where there’s wind, you feel it. The rain wets you down, and the sun dries you out. You hit a bump in the road and maybe land in a ditch. You get mud on your feet.

That was the way I liked it. I didn’t want Africa to be something on the other side of a car door. I wanted to feel every inch of the wildest continent passing under my little wheels and to be right out there where I could touch it.

When I arrived in South Africa, I was out to win a bet which came up one night with that Dutch captain over a game of cards. Scooters came into the conversation, and he got my dander up with a remark that these little fellows could never negotiate really rough country.

By the time Cape Town loomed on the horizon a few days later, I had made up my mind to prove the captain wrong. If there were a place in Africa too rough for a scooter, I would find it. Did I? That’s another part of the story.

I checked all the scooter agencies and finally wound up at Lambretta’s, my old favorite. Once the Road Angel was mine, I took a trial run along the Garden Route from Cape Town to Port Elizabeth, a distance of about 500 miles over good but climbing and twisting highway. She was broken in by the time I got back, and already I was in love with her.

The big journey began from Cape Town at dawn on an October day. The trip had been carefully planned to coincide with the best traveling season in all parts of Africa — summer south of the Equator and winter after that; summer in the rolling veldt and cool mountains of South Africa, the dry bush country of the Rhodesias, the high plains of Tanganyika and the White Highlands of Kenya; winter in the hills of Uganda, the steaming jungles of the Congo, the swamps and marshes of the southern Sudan and the hellish desert of the northern Sudan and Egypt. The idea was to miss the rainy season in the south and the dry spell in the north.

Striking out on the Great North Road that morning was one of the grandest moments of my life. The Road Angel, still known only as “the scooter,” rolled along in her coat of blue and gray paint as shiny as a young girl on her first date.

Actually, she looked more like a pack mule. Hanging on either fender, strung together under the pillion seat, were two knapsacks fat with cooking equipment, a hatchet, a flashlight, clothing for all conceivable weather changes and sundry paraphernalia. Her rear luggage rack boasted a rolled tent (larger than pup size), a sleeping bag and other gear. At knee level, behind the steering column, a small suitcase containing books, maps, field glasses and a compass nestled in a> rack I had created from angle irons and attached by boring holes and inserting nuts and bolts.

I carried no gun. Courage? No, I was such a lousy shot I figured the only thing I could shoot would be me.

On my head was a romantic-looking sun helmet. I’d wanted a crash helmet, but the hot African sun forced me to allow for more shade on my neck and face than the crash style gives.

As it turned out, the trip through South Africa was little more than a trial run for the rest of the journey. The country introduced me to the four kinds of wilderness existing in Africa: savannah, desert, mountain and jungle — all of which have to be coped with along the way. But in the south, these introductions just scratch the surface, like a vaccination against the really big things to come. For a good breaking in, anyone making the trip would be well advised to start at the Cape as I did.

My route through this part of the continent took me north as far as Kimberley, home of The Big Hole — the world’s most prominent example of surface diamond mining. Here also was found the great Koh-i-noor diamond, as well as the Cullinan, worth a million pounds before cutting. From Kimberley I cut southward again through Bloemfontein to Port Elizabeth and then up the Indian Ocean coast to East London before heading inland to Umtata and thence to Pietermaritzburg, the mountain-ringed capital of Natal province. In the Valley of the Thousand Hills, named by our own Mark Twain during a South African visit in the nineteenth century, I first met the Zulus — one of the most respected and civilized of African races.

The Road Angel never faltered once over all those “thousand” hills. She had begun to give me every indication o£ the fantastic endurance she would show later. However, we both underwent a terrifying experience after leaving Durban, “the Miami Beach of South Africa,” to travel on the road to Lourenco Marques, capital of Mozambique.

Having chosen to go to Johannesburg via the cosmopolitan Portuguese city of lovely women and sidewalk cafes, I pitched camp near the road one night on the heels of a fast African sunset. The sun seemed to drop out of sight in less than a minute, and it was suddenly night. I set up the tent in semi-darkness, only being able to see a distance of a few feet on either side. The ground was soft; I knew this was no proper place for camp, but I had no choice. I slept well enough and got up with the sun the next morning. Then I saw I was smack in the middle of a swamp, about twenty feet from brackish water — a dangerous place in Africa.

I strolled over to the Road Angel to fetch my toothbrush. As I reached into the knapsack, I glanced at the rear luggage rack, where I always kept the rolled tent. It should have been empty now, but it wasn’t.

Casually looped around it like a kid on a Jungle Jim was a very long, very thick shoelace — but nobody in the world ever tied a shoe with the snake known in Zulu as Muriti-wa-lesu (“The Shadow of Death”) — the black mamba. At the time, I didn’t know the mamba was a mamba. I found that out later. But snakes had always been snakes to me, and the particular type never made any difference.

I couldn’t move. I guess he couldn’t either. We stared at each other for a long time. Then I decided, “Oh, what the hell!” And with one rapid thrust, I kicked the prop stand under the Road Angel and over she went — in the other direction, thank God. And away I went just as fast as I could run. When I came back half an hour afterward, the mamba was gone, but the Road Angel looked a little sad with her bottom turned up in the air.

In Lourenco Marques I was told that mambas are the cleverest snake on earth; they’ll track you down if you’ve done them wrong.

Johannesburg was the last big city I was to see until I reached Cairo. Tall skyscrapers and fabulous entertainment kept me in Jo’burg for a while, but I was anxious to hit the path again. I left and went by way of Pretoria and Louis Trichardt to Beit Bridge, jumping off place into the wilds of Africa. I crossed the Limpopo River and entered Southern Rhodesia. To my left lay a magnificent paved road leading off through the bush, with a sign pointing audaciously to Victoria Falls, the Congo and Cairo. This was the continuation of the Great North Road.

“Is that the road to the lost city of Zimbabwe and to Salisbury?” I excitedly asked the young native at the filling station.

He looked at me as though he thought me crazy and then pointed to another road I hadn’t noticed: two strips of

concrete set apart to accommodate the right and left wheels of a car, each strip being only a trifle wider than the Road Angel’s wheels. The road vanished in the haze of heat rising from a flat, desert-like plain sprinkled with brown grass and scrub trees.

“That’s yours,” said the boy.

My heart jumped into my mouth. Had I asked for this? Once out there, I would pass the point of no return. I sat atop the Road Angel, her nose turned toward the bush country, and toyed with the tiny silver cherub dangling from her handlebars. That little angel would have had only one thing to say if it could talk, and the Road Angel probably would have agreed. The majority ruled. I turned my back on the blacktop and took to the bush on two wheels.

Mile after monotonous mile went its way behind me as I passed the bridges called Bubye and Nuanetsi. My speed over the strips averaged 45 mph, although the posted limit was 50, the legal limit allowed for vehicles assumed to be capable of taking the holes in the road in a single leap. The scooter took them in two, and twice I literally flew.

Salisbury, the first city lights in the nighttime sky after the thousand miles from Johannesburg; Bulawayo, another Rhodesian city, where the streets are laid out wide enough for an eight-deep oxteam to make a comfortable U-turn; and Victoria Falls, a series of magnificent gorges always laced with rainbows — this was the route I followed to the Zambesi River. Into Northern Rhodesia, where I passed through towns boasting gun-totin’ cowboys crowded into swinging-door saloons, and all the way to Tanganyika by way of Lusaka and Broken Hill, the Road Angel sailed along.

There were two serious mishaps along the way. When she ran out of gas fifty miles from the closest filling station, I discovered that the jerry can I’d attached in Salisbury over her front wheel had sprung a leak and left a trail of gasoline all the way from Broken Hill. Fortunately, after only three hours of sitting in the hot sun, a car came along driven by a kindly gentleman who had a heavy supply of “petrol” in the trunk. He told me that his son had once run out of gas in the Belgian Congo — sitting it out for three days before anyone came along. From then on, the father always carried an extra jerry can for hapless fools like his son and me.

But the more serious accident took place on an evening when I couldn’t find a place to pitch camp and had decided to keep going the twenty miles to the next town. Thanks to goggles, windshield and insects, I didn’t make it that night.

The largest and toughest bug I’d ever seen went right through the windshield and spattered my goggles, leaving a jagged hole in the shield as large as a fist. Then the Road Angel came to a quick dip in the road at the bottom of which was a foot-deep puddle of water and some scattered rocks — and I was too blind with bug blood to see it in time. She hit the water and rose into the air like a bucking bronco, striking with such impact that a spray of water and rocks geysered up and rained down like hail. The weakened windshield was ripped apart at the first blow. The force of air from a speed of 40 mph swept the Road Angel’s nose up fully five feet off the ground. She came down ten feet from the road.

I spent the night unconscious by her side, and when I woke up in the morning, I discovered my only damage to be a badly twisted wrist. As for the scooter, I cleared away the remains of the shield, uprighted her, and let her stand there for awhile to let her innards settle info their rightful place. Five quick depressions of the pedal — and her motor hummed like a happy child. I vowed then that I would forever be a good boy and would give daily thanks to Lambretta for creating a masterpiece of mechanics.

The roads through Tanganyika were monotonous at first, with long stretches of bad surface until I reached the steep cliff escarpments that mark the edge of the Rift — a monumental gash through the heart of Africa caused by some prehistoric upheaval. Sinuous hut well-graded, the climb into the highlands offered magnificent scenery, and gas stations, although few and far between, were seldom dry, which often happened later in the northern deserts. Beyond Morogoro, I passed the teeming cotton market at Kingolwere and began to enter the region of sisal plantations. The season was dry; this road had a reputation of being impassable at times during the rainy season. Finally, Dar-esSalaam, “Haven of Peace”, came into view, strung like a shiny necklace around its harbor on the Indian Ocean.

The lure of an exotic island off the coast became a siren call, so I paid double fare, and the Road Angel and I took the short voyage to Zanzibar.

Word had reached the Sultan of the Isle of Cloves that a young American was paying a visit in transit from the Cape to Cairo. To hear his representative tell it when I called at the palace, the ruler was rather taken by the whole foolish notion. Therefore, said his aide, would the Road Angel and I accept an invitation to sail back to the mainland in the royal dhow? Now, whether that was a quick kick out of the country or not, nothing impressed me more than a voyage in one of the most beautifully designed crafts man has ever created. Consequently, the Sultan’s silk sails unfurled for me and the Road Angel, and back to Dar we floated in style. On the way, the captain told me of another dhow — the traditional passenger and cargo vessel between East Africa and India — that rode before the monsoon from Bombay till it hove within sight of Zanzibar on the fortieth day. Then the wind changed — and blew it right back again. No such luck, this time, though, for the Road Angel and I were soon on our merry way to Tanga and thence along a hundred miles of unspoiled beach — with the Indian Ocean on one side and cocoanut palms on the other — to Mombasa, a city where two gigantic elephant tusks form an arched entry into town.

Sitting on a reef offshore from the Nyali Beach Hotel, I chatted with a young couple who had recently become residents of Mombasa after a serious Mau Mau scare in their part of Kenya beyond Nairobi. They couldn’t take that sort of nonsense, they said. But when I told them a story I’d heard at the hotel, they wildly swam back to the beach, wondering if they’d traded one kind of terror for another. It seems that from that very reef not long before, a young boy had been dragged beneath the waves by a mysterious unidentified sea monster.

As for me, I couldn’t stand being out there alone and raced to shore almost feeling that thing grab at me from below. But monsters of the land variety would be my chief concern for the next few weeks during a journey to the Congo from the East African coast through the great game country of the Serengeti Plains and the Ngorongoro Crater. Among other things, a Tanganyika lion would get revenge on his South African cousin’s would-be lunch in a most peculiar way, and I was soon to meet the seven-foot “moon men” of the Ruwenzori — in company with a three-foot friend. •