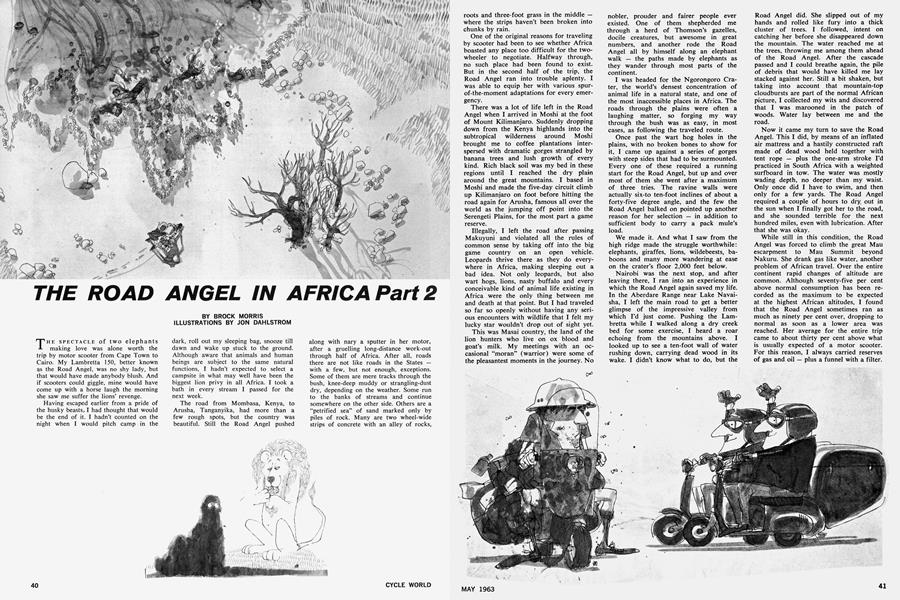

THE ROAD ANGEL IN AFRICA Part 2

BROCK MORRIS

THE SPECTACLE of two elephants making love was alone worth the trip by motor scooter from Cape Town to Cairo. My Lambretta 150, better known as the Road Angel, was no shy lady, but that would have made anybody blush. And if scooters could giggle, mine would have come up with a horse laugh the morning she saw me suffer the lions' revenge.

Having escaped earlier from a pride of the husky beasts, I had thought that would be the end of it. I hadn't counted on the night when I would pitch camp in the dark, roll out my sleeping bag, snooze till dawn and wake up stuck to the ground. Although aware that animals and human beings are subject to the same natural functions, I hadn't expected to select a campsite in what may well have been the biggest lion privy in all Africa. I took a bath in every stream I passed for the next week.

The road from Mombasa, Kenya, to Arusha, Tanganyika, had more than a few rough spots, but the country was beautiful. Still the Road Angel pushed along with nary a sputter in her motor, after a gruelling long-distance work-out through half of Africa. After all, roads there are not like roads in the States -with a few, but not enough, exceptions. Some of them are mere tracks through the bush, knee-deep muddy or strangling-dust dry, depending on the weather. Some run to the banks of streams and continue somewhere on the other side. Others are a "petrified sea" of sand marked only by piles of rock. Many are two wheel-wide strips of concrete with an alley of rocks, roots and three-foot grass in the middle — where the strips haven't been broken into chunks by rain.

One of the original reasons for traveling by scooter had been to see whether Africa boasted any place too difficult for the twowheeler to negotiate. Halfway through, no such place had been found to exist. But in the second half of the trip, the Road Angel ran into trouble aplenty. I was able to equip her with various spurof-the-moment adaptations for every emergency.

There was a lot of life left in the Road Angel when I arrived in Moshi at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro. Suddenly dropping down from the Kenya highlands into the subtropical wilderness around Moshi brought me to coffee plantations interspersed with dramatic gorges strangled by banana trees and lush growth of every kind. Rich black soil was my bed in these regions until I reached the dry plain around the great mountains. I based in Moshi and made the five-day circuit climb up Kilimanjaro on foot before hitting the road again for Arusha, famous all over the world as the jumping off point into the Serengeti Plains, for the most part a game reserve.

Illegally, I left the road after passing Makuyuni and violated all the rules of common sense by taking off into the big game country on an open vehicle. Leopards thrive there as they do everywhere in Africa, making sleeping out a bad idea. Not only leopards, but also wart hogs, lions, nasty buffalo and every conceivable kind of animal life existing in Africa were the only thing between me and death at that point. But I had traveled so far so openly without having any serious encounters with wildlife that I felt my lucky star wouldn't drop out of sight yet.

This was Masai country, the land of the lion hunters who live on ox blood and goat's milk. My meetings with an occasional "moran" (warrior) were some of the pleasantest moments in the journey. No nobler, prouder and fairer people ever existed. One of them shepherded me through a herd of Thomson's gazelles, docile creatures, but awesome in great numbers, and another rode the Road Angel all by himself along an elephant walk — the paths made by elephants as they wander through most parts of the continent.

I was headed for the Ngorongoro Crater, the world's densest concentration of animal life in a natural state, and one of the most inaccessible places in Africa. The roads through the plains were often a laughing matter, so forging my way through the bush was as easy, in most cases, as following the traveled route.

Once past the wart hog holes in the plains, with no broken bones to show for it, I came up against a series of gorges with steep sides that had to be surmounted. Every one of these required a running start for the Road Angel, but up and over most of them she went after a maximum of three tries. The ravine walls were actually six-to ten-foot inclines of about a forty-five degree angle, and the few the Road Angel balked on pointed up another reason for her selection — in addition to sufficient body to carry a pack mule's load.

We made it. And what I saw from the high ridge made the struggle worthwhile: elephants, giraffes, lions, wildebeests, baboons and many more wandering at ease on the crater's floor 2,000 feet below.

Nairobi was the next stop, and after leaving there, I ran into an experience in which the Road Angel again saved my life. In the Aberdare Range near Lake Navaisha, I left the main road to get a better glimpse of the impressive valley from which I'd just come. Pushing the Lambretta while I walked along a dry creek bed for some exercise, I heard a roar echoing from the mountains above. I looked up to see a ten-foot wall of water rushing down, carrying dead wood in its wake. I didn't know what to do, but the Road Angel did. She slipped out of my hands and rolled like fury into a thick cluster of trees. I followed, intent on catching her before she disappeared down the mountain. The water reached me at the trees, throwing me among them ahead of the Road Angel. After the cascade passed and I could breathe again, the pile of debris that would have killed me lay stacked against her. Still a bit shaken, but taking into account that mountain-top cloudbursts are part of the normal African picture, I collected my wits and discovered that I was marooned in the patch of woods. Water lay between me and the road.

Now it came my turn to save the Road Angel. This I did, by means of an inflated air mattress and a hastily constructed raft made of dead wood held together with tent rope — plus the one-arm stroke I'd practiced in South Africa with a weighted surfboard in tow. The water was mostly wading depth, no deeper than my waist. Only once did I have to swim, and then only for a few yards. The Road Angel required a couple of hours to dry out in the sun when I finally got her to the road, and she sounded terrible for the next hundred miles, even with lubrication. After that she was okay.

While still in this condition, the Road Angel was forced to climb the great Mau escarpment to Mau Summit beyond Nakuru. She drank gas like water, another problem of African travel. Over the entire continent rapid changes of altitude are common. Although seventy-five per cent above normal consumption has been recorded as the maximum to be expected at the highest African altitudes, I found that the Road Angel sometimes ran as much as ninety per cent over, dropping to normal as soon as a lower area was reached. Her average for the entire trip came to about thirty per cent above what is usually expected of a motor scooter. For this reason, I always carried reserves of gas and oil — plus a funnel with a filter.

I never knew what kind of trash to expect in the gas and oil sold in the African back country.

Naturally, water purification tablets were always handy, as were a mosquito net and tire chains — only a small part of the equipment needed to assure safety while traveling in a continent where stores and garages are far from one another. In Central Africa, I also carried anti-malaria pills, essential among the swampy areas around Lake Victoria.

Traveling through the rest of Kenya and into Uganda was fairly uneventful. Until reaching the Belgian Congo, the Road Angel had no trouble of any kind once over the cloudburst ordeal. Before that, I visited the Ruwenzori, better known as the Mountains of the Moon. Here I met two Swiss boys, on their way to Europe, who shared my mosquito net in the foothills after losing theirs in a shack which caught fire while they were there as guests.

Their scooters were Vespas, and a look at these slick machines momentarily turned me green with envy. Metallic paint, of course, was the dressiest aspect, along with the wasp-like backside which is the trademark. But the most interesting point of the get-up was the custom-installed facility for equipment, which the boys claimed they had designed themselves for execution at a Vespa workshop in South Africa. An aluminum box about three feet square by three feet deep was mounted securely on the rear luggage rack after removal of the pillion seat. A removable tray in the top held toilet articles, maps and the like, while everything else, including the tent, was fitted into the bottom section. No windshield broke the sleek lines, and there were no cumbersome racks like the Road Angel's to add extra weight. The boys wore leather jackets and flight goggles and crash helmets to match the scooters

— all in all, a great outfit put together with speed in mind. Their only problem

— not so bad on good roads — was balance, but they'd schooled themselves to manage it. I often wondered later how they fared in the desert. However, they were to take the Western Sahara route which boasts fine roads. I had a letter from them in Cairo after they'd finished the trip, telling me that those fancy aluminum boxes were sitting somewhere in Nigeria. There they'd had to distribute their gear like mine because the sandy tracks in some places had made perfect balance of the utmost importance.

They went ahead of me through the Congo while I paid respects to a friend of a friend, who took me into the country nearby where gorillas, "moon men" of the Ruwenzori, come down from the mountains to look for wild celery to munch on. I had the honor of seeing two of the seven-foot monsters while sharing the Road Angel with a three-foot pygmy along for a joy ride. It came as a surprise to all of us; we went in several different directions. Afterwards, it occurred to me that I probably held the world's record for "taking it on the lam." Lions, snakes and gorillas just weren't my meat! The same could be said for my pygmy companion, although I saw his tribe eat an elephant — raw.

At the Congo border, I was treated with suspicion. They trusted no one fool enough to travel through jungle on a scooter. However, I had all my papers, and considering the trouble I'd gone through to get them, I was damn well determined to at least get into the country. The South African Automobile Club had issued me a "triptych" of strip maps and authorization to pass through the nations on route. The one for the Congo had cost a pretty penny, refundable after I was safely out of the place. Actually, this "carnet" was a bond posted to guarantee not only my departure within the limitations of my visa, but also payment for any breakdowns I might have there. For four-wheel vehicles, the charge was only $50, but two-wheelers were regarded with such distrust that my bond was set at roughly $450, more or less the scooter's value when new.

I got in, but I didn't think I'd get out again when I ran into road trouble in the rain forests north of Beni Junction. Another washout typical of several I'd encountered in Africa had left a strip of deep mud in its wake. So I resorted to an old pioneer trick called "corduroying." Laying out all the strips of wood I could find, I unrolled the tent over them and pushed the Road Angel to the end of the section I'd laid — and then started over again. Twenty-five tent lengths later, I was back on the road, taking more mud with me than I'd left behind.

The remainder of the Congo trip took me through strange native villages where children and dogs chased me and in which I counted more than two hundred naked girls who would make Sophia Loren look skinny. There were also large mining settlements where heavy trucks had made short work of what must originally have been good roads. The scenery was glorious, when I had time to notice it, from the sinuous, hilly roads, but the highlight of this section was a visit to the school at Faradje where Indian elephants are trained for jungle-clearing work the wilder African variety can't be tamed to do. Continuing fifty miles eastward from Faradje, I came to the Congo-Sudan border and headed for Juba.

At Juba, I became a fugitive, almost a "desert outlaw" — and the Road Angel barely escaped imprisonment at the hands of Sudanian customs officials. Arriving at the customs depot, a hundred miles from the Congo border, I was questioned carefully about just what I planned to do with "that machine." I did not plan to cross the desert with it, of course, after reaching Khartoum — in the opinion of the officers. They produced a lengthy statement which everyone who contemplates traveling through the Sudan by motor vehicle must sign. This included all sorts or requirements which looked nasty to me: not two wheels, but four; a convoy group for mutual protection; such and such an amount of extra gas and oil and water (far exceeding the amount the Road Angel could bear) and other stipulations I could not possibly meet. The Sudan was thus relieved of all responsibility for my death if I should be foolhardy enough to make the trip.

At first I was discouraged. Then I became furious (but with the sweetest smile on my face), for hadn't the Road Angel made it this far and wasn't I still alive to tell the tale? A small particle of wisdom came to my rescue. No, I told them, I was headed back for Kenya after Juba. But they didn't trust me. The Road Angel, they said, would have to stay in Juba; I could send for it from Nairobi. (This illustrated another point I'd endeavored to take care of everywhere. In securing visas for each country, I had specifically requested "multiple entry" privileges to cross and re-cross borders where necessary, instead of the usual one entry and one exit allowance. So in Juba, for example, I was able to produce a visa to show that I was cleared for re-entry into Kenya, even though I had earlier entered and left it twice.)

At this point, one of those magnificent tricks of fate that crop up every once in awhile to save a person in the last extremity came up with my number on it.

"Well," said I, "what the hell! There's nothing to see in the Sudan anyway!"

That did it. The officials were so upset that they wound up regaling me with all the wonders of their great nation. An hour later, I was comfortably ensconced in a government rest house waiting for a police convoy scheduled to leave the next day for Malakal, nearly four hundred miles farther north in the Sudan — with the understanding that from there I could arrange with BOAC to fly one way or other, provided it was out of the country.

To Malakal the Road Angel drove beside a truck, keeping in line with the law, but once there, the truck driver and I had become such good friends that when no one was looking he tucked the Lambretta and me into the back of his vehicle and illegally deposited us several miles out on the other side of town.

The next five hundred miles to Khartoum, I skirted around government representatives and district commissioners. My compass became important through this section of the journey. Some of the roads were very difficult to follow, and some weren't even there. A couple of bridges had been ripped apart by the elephants which were the scourge of the region, requiring me at one point to cross a stream on exposed girders designed for nothing bigger than ants. The country through here was lush, green and swampy, with vast numbers of the last big game I was to see in Africa — as well as the most colorful natives I had yet run across. Gas pumps were a rarity, but when I found one, I always filled my jerry cans (I'd added another one in the Congo, on the rack that once held the little suitcase containing books), and nobody ever asked for my identity papers. Whereas in most of Africa gas had cost anywhere from 35 cents to a dollar per gallon, depending on availability, at one point in this section, I made hisiory by paying $5 a quart!

All this distance was covered near the banks of the White Nile, and not one bridge did I see across it until a little more than 200 miles south of Khartoum, at Kosti — where I entered the Gezira, an irrigated region as fertile as any tropical garden. The tracks through the Gezira tended to vanish every once in a while, disappearing completely 150 miles south of Khartoum. From here I had a terrible trip to the capital, following the main irrigation canal and eventually bumping along the railroad tracks for about 50 miles. After that the Road Angel began to make muted but unhappy noises in her depths.

I smelled Khartoum before I saw it: no sewage system. I replenished my supplies, but dared not stay in the one good hotel for fear of getting caught and shipped out. I hit the road again soon after arriving.

Now I was in doubly dangerous territory — the world's worst desert lay before me; and by entering it illegally, I had denied myself the privilege of sending the departure and arrival telegrams from points along the way — telegrams used to keep track of convoy and private party movements to determine whether a rescue search is necessary.

I proceeded 350 miles north of Khartoum to Abu Hamed, where I took an important precaution. All metal parts of the Road Angel which I would be likely to touch, I covered with wooden frames. It was no "custom" job, but a strictly home-made affair resembling cartoon sandwich boards held together with rope and navy knots. In the hottest place on earth, I couldn't afford to take any chances on burning myself to death on exposed metal. There, 115 degrees in the shade (if there was any) was considered "cool." My clothing was heavy and white, and I draped a scarf around my face from the nose down (for the first time since losing the windshield in Tanganyika, I missed its protection) and a cloth dangled from the back of the sun helmet to cover my neck.

Looking like a Lawrence of Arabia "on relief," I crossed the Nubian Desert — more than ever a fugitive from Sudanian justice, and, frankly, I wished later that they'd shot me at Juba! Always I kept the railway in sight, and once I saw the famous air-conditioned train whiz by with all its comfortable passengers. I stopped at the railroad stations — lonely places with numbers instead of names — and spent a night at Station 6, renowned as the only spot with water along the route through the Great Eastern Emptiness of the Sahara. The distance was only about 200 miles to Wadi Haifa, but the heat and the roadless wastes kept me going for four days, with one night of moonlight riding to boot.

My real problem here was soft sand. Anyone who has ever ridden a scooter will know what that means. Through most of the soft parts, I walked, pushing the Road Angel. But then I got the idea of "fighting fire with fire" and glued tire patches at close intervals around both tires, scraped them to make them rough and applied layer on layer of glue and sand and drops of water until I had a hard, sandpapery surface that, when dry, gave me much more traction than grooved rubber. Still, I had a lot of walking to do and later thought that the treatment hadn't been worth the trouble. After Wadi Haifa, when I really needed traction all the time, I added tire chains and more glue, sand and water. But it got so hot that the glue never really became anything but "goo."

From Wadi Haifa, I embarked on the beginning of the end of the Road Angel. No one was supposed to venture into the hellish wastes between Wadi, last town in the Sudan, and Shellal in Egypt — about 300 miles: no railroads, no villages, nothing except the Nile and the desert. To make a long story short, I got lost, even with frequent piles of stone to guide me on the general route. The heat was terrible, and to retell the agony of those ten days on light water rations and little food is unbearable to this day. The Road Angel was almost useless for the most part, but when I stumbled into the Nile halfway to Shellal and had the great good fortune to find a tiny nomadic settlement where I could wait for the Nile steamer headed downriver, she was still with me.

On the twelfth day, the steamer was flagged down and picked up both of us. I had a lot of explaining to do when I got to Egypt, but the authorities were so surprised to see me alive that I got off with a scolding — which I deserved. From Aswan to Luxor, the Road Angel — full of sand and trouble, but determined to make it even if she were on her last wheels — made decent time.

Luxor was where I decided to make a liar of myself. I would later say that I had traveled from the Cape to Cairo on the motor scooter. But I did not. The Road Angel could not go that last 440 miles with me. Her endurance, which I consider magnificent in light of the trial she had been through, would forever remain a credit to Lambretta. She had accomplished her job and now was ready to be done with it.

We made one short trip together across the Nile from Luxor — to the tombs of ancient Egyptian kings. There, it was the Road Angel herself who actually made the final decision. She just wouldn't go anymore. The desert trip had been too much. That's where I left her — in the Valley of the Dead, with other royal ruins.

I took a train to Cairo, and all I had to remind me of my Lambretta 150 was the little silver cherub that used to dangle from her handlebars. The same cherub hung on Road Angel II in India a few weeks later, but, somehow things weren't quite the same. •