BSA 650 LIGHTNING

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Doth The New Look A New Motorcycle Make?

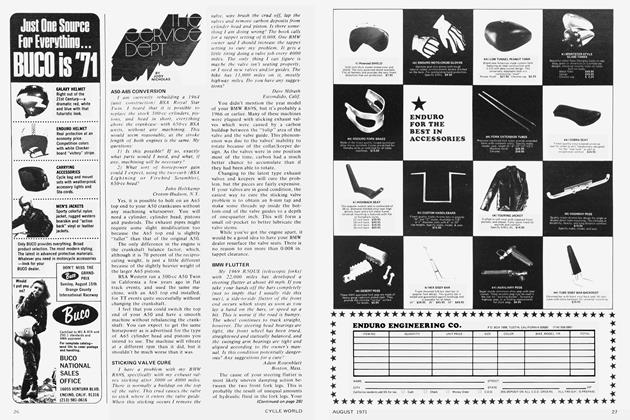

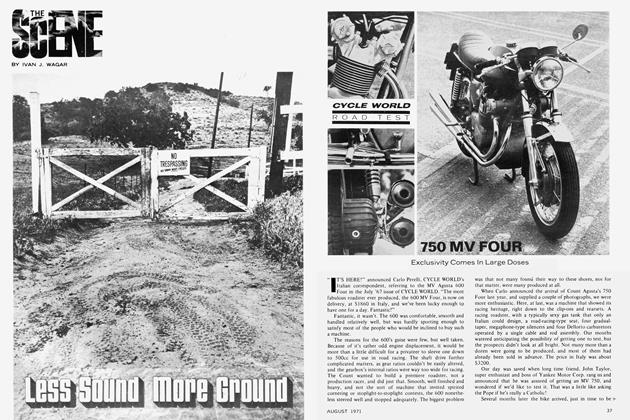

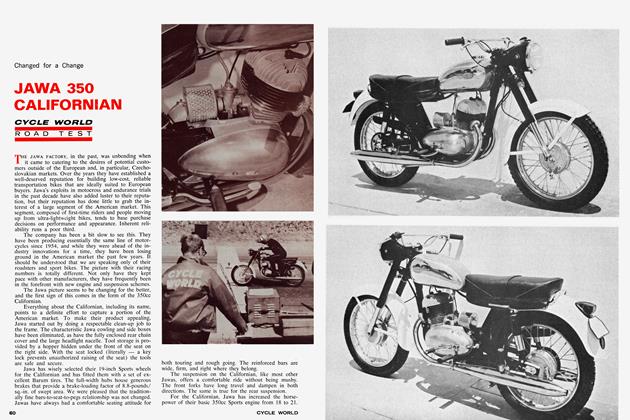

THE STYLISTS SPARED nothing in updating the external appearance of BSA’s new line of 650s. The new Lightning, counterpart to Triumph’s new Bonneville, looks much better than the Bonneville.

Normally, styling would be of small concern to a person who would buy a British Twin. But performance of the two machines is virtually identical, and both the Bonnie and the Lightning share the same new frame design and running gear. So the BSA gets the better looks. It’s all part of a plot to revive the sagging BSA line in the U.S. BSA stands for the initials of the parent company of Triumph and BSA, Birmingham Small Arms. We can surmise that in their eyes it’s no good to have Triumph outselling the namesake of the parent, right?

Whatever the motivation, the treatment is quite attractive. Since time immemorial, the frame tubes on British machines have been painted black, and still are so on the Triumphs. BSA has now switched to ivory painted frames, which has the effect of attractively emphasizing and outlining that function of the machine and setting it off from the engine and other parts. By comparison, a black frame seems to hide itself and disappear in the jumble of other mechanical parts which make up a motorcycle.

As with the Triumph Twins, the Lightning frame is new, better in some ways, annoying in others. Its main structural member is a large diameter, L-shaped spine tube. The rearward portion of this tube doubles as the oil tank. This offers a few advantages: elimination of the need to mount an external oil reservoir, and increased surface area of the oil container tube, which gives more effective heat dissipation. The oil filler cap is located on the bend of the spine frame; it is quickly reached by unsnapping the seat fastener with the thumb and raising the hinged seat. However, if the oil level is slightly down, it takes some careful peeking in that dark, small hole to see how far down it is. Perhaps a flexible dipstick, to follow the curve of the spine, is in order.

The other disadvantage is produced by a combination of styling considerations and the generous thickness of the spine just behind the steering head. BSA, tiring of the classic Beeza look, wanted to make their Twins slimmer and sexier, which they did—admirably. This, of course, means slinging a narrower, lower fuel tank over that fat spine tube. To make the deep metallic orange and white tank even more beautiful, they have ornamented it with what we can call a “masculinity” band running the length of the topside. The slim top of the tank and that metal band (which may be useful in that it. prevents objects strapped to the tank from scratching the paint) conspire to demand a centerline gas cap location. Open the cap and what do you see? Gasoline, if the tank is full. Or, the hump of the spine tube, if the gas tank is less than three quarters full. So you peek around the side of the filler hole, or shake the bike sideways to hear how much gas is sloshing about. One of us ran out of gas while developing his ear for sloshing.

In a way, these impracticalities are delightful. After all, the bike is beautiful and more compact looking. And a little frivolity can’t hurt jolly old BSA, nor us BSA riders, who are a frivolous lot anyway.

On the practical side, the large spine tube frame, in combination with a full double cradle, is hard to fault, as it is quite strong and flex-free. The BSA/Triumph design also dispatches one common objection with frames that carry oil which has to do with contamination of the oil reservoir with metal bits, should an engine blow. The bottom end of the BSA’s spine has a removable cap, so the reservoir may be easily emptied and flushed. Further protection comes in the form of an inverted basket screen which strains the oil as it enters the reservoir from the engine.

Along with the new frame comes the new forks and conical hub assemblies which grace the Triumph 650s. These provide a vastly improved ride over the old BSA Twins. The ride is stiller, but the reward is a lighter feeling, and a more stable machine, nimble in town and encouraging derring-do in the swerving outback. The Lightning may be stuffed hard into a turn until everything grounds (more so on the left, because of the projecting centerstand). The 3.25-19 front tire, smaller than last year’s front, allows great steering precision. Point the bike and it stays pointed. The bike is definitely one of the best handling big Twins we have tested, and certainly the best to come from BSA in a long time.

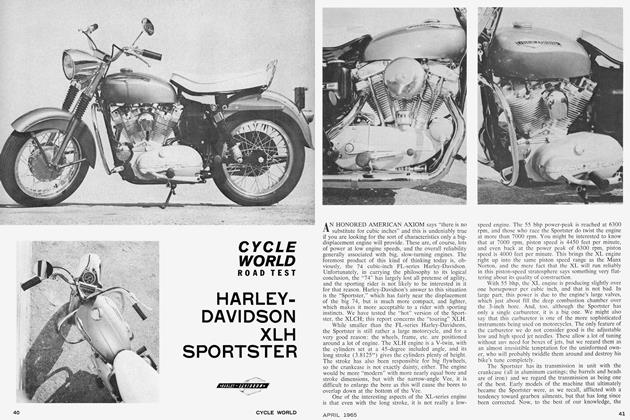

BSA’s powerplant, one of the few things left to help you tell Trumpet and Beeza 650s apart (assuming you are colorblind), is much the same as in recent years: a slightly oversquare (75mm by 74mm), pushrod vertical Twin with 9.0:1 compression ratio. Even in dual-carb Lightning trim, it is in moderate tune, and therefore offers a fairly broad powerband, docile low-speed running, and easy starting. This is somewhat of a retreat for BSA, who were pushing a faster 650 called the Spitfire a few years back. Now that they have the 750-cc Three, the Lightning takes over as head Twin-one that is much easier to live with.

Modifications to the engine for 1971 are few, save for the incorporation of the cylinder head steady into the rocker box casting, and the adoption of megaphone-shaped silencers, which not only look good, but really do a proper job of public relations while retaining enough deep timbre to allow the rider to feel like he is riding a ballsy machine.

The generous amount of mechanical noise revealed, perhaps because the silencers are more effective than in past years, is disappointing. It is most evident in the form of whirring and clanking from the lower regions, particularly with little or no load on the engine. The effect was similar, though not as pronounced, on the Bonneville, which has improved silencing, too. The BSA engine also vibrates at some rather unstrategic points in the rpm scale, notably at 3500 rpm to 4000 rpm. Unstrategic, we say, because these rpm figures correspond roughly to speeds in high gear of 55 to 65 mph. Above 4500, the vibration, which tickles feet and hands, starts to disappear.

We don’t recall that the same engine vibrated as much in preceding years, which would suggest that the frame tube thickness or the frame mounting points are “unsympathetic” to the engine. Sometimes the engine balance factor must be changed for a new frame. While BSA is figuring out what it is, the long distance touring rider can solve the problem somewhat by gearing higher overall.The Lightning is certainly capable of pulling higher gear. Handlebar jiggles, not as noticeable as those that set the feet to tingling on long freeway runs, could be reduced with narrower bars.

At any rate, one may well notice that the most popular big Twins are set up for the American market as around-town hot rods. Wide bars, low gearing, etc. Go to a country in Europe or the British Isles where big Twins are more often used for travel, and you will find that the bikes are presented to the buying public in different form.

The Lightning gearset will please some and irritate others. Unlike the Triumph 650 Twin’s four-speed unit in which the ratios are more or less evenly spaced, BSA puts a larger gap between 2nd and 3rd gears, thus making 3rd closer to 4th. This will infuriate racing types, and immensely please road riders, who will like the superb 50 to 90 mph passing power afforded by 3rd gear.

Performance of the gearbox itself is excellent. Shift travel is short and engagement is precise, with no evidence of grinding when things are done in a hurry. The right-hand shift pattern is down for low, up for higher gears. The clutch also performs faultlessly, firmly, drag-free, and its engagement is smooth and progressive.

The new layout for electrical components is excellent. Lift the aforementioned hinged seat, and you find the dual coils, battery, wiring (as well as the toolkit) all in sensible, roomy array.

The Lucas switches on the handlebars, which we criticized on the new Norton and Triumph Twins for being oddly placed and difficult to operate, are the same on the Lightning.

Seating is quite comfortable and not overly high at 32.5 in.; this comes as a pleasant surprise, for the new Bonneville, which has the same frame, has a seat 34.5 in. high, overly tall for a rider with short legs.

Undoubtedly, our references to Triumph will encourage readers to ask whether they should buy the Lightning or the Bonneville. It is hard to give a definite answer, for BSA and Triumph are in the same position with these two machines as Chevrolet and Pontiac are with the Camaro and Firebird. Both machines are basically alike, use identical frames, have slightly different engines of similar configuration, and have perceptible differences in styling.

Perhaps it is a question of image, for each machine has good and not so good things about it.

In the case of the BSA, you get a good sports roadster with excellent handling. It is most definitely all that a big-bore four-stroke parallel Twin from Great Britain has traditionally connoted. Only now, its look is more refined, up-to-date, and the new frame and rolling gear is a delightful come-on.

Whether true or false, Triumph Twins have had a better reputation for reliability than have the BSA Twins. BSA, of course, is doing their damnedest to improve their image in that respect.

In the end, BSA’s success may depend heavily on styling, and seat height. On smoothness, the Bonneville is favored slightly. On handling the BSA just edges the Bonneville.

In short, the choice is a toss-up, a question of taste.

BSA

650 LIGHTNING

List price............. $1474