Stanboli Attacks MotoGP!

ROUNDUP

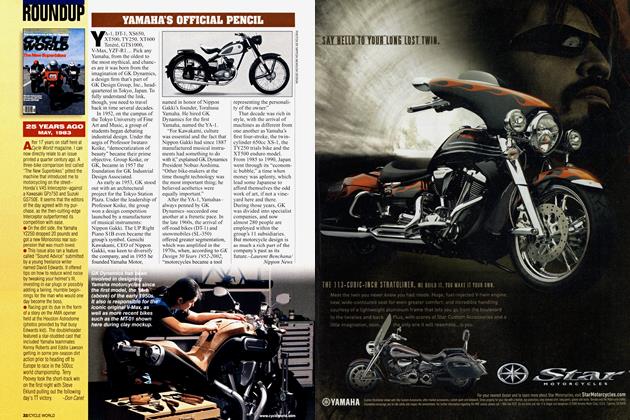

Attack Performance is building its own 1000cc CRT MotoGP bike

KEVIN CAMERON

ATTACK PERFORMANCE HAS BEEN GRANTED WILD-CARD entries for rider Steve Rapp this summer at the Red Bull U.S. Grand Prix at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca and Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. All formalities are in place. Now, all team owner Richard Stanboli has to do is what has never been done before: build the first-ever American MotoGP Claiming Rule Team (CRT) entry. Stanboli is in the process of fabricating his own chassis, using a unique aluminum alloy that requires no post-weld heat-treat ment for strength. "We can make the parts," he said. "We have the computer power. And the electronics are right up the street."

MotoGP is a pure racing class for which factories build prototype ma chines designed only for competition. Because of economic conditions, this year, for the first time, the class will also include so-called CRT entrieslower-cost racing machines whose purpose is to keep smaller teams in the game. Stanboli is building such a machine, which is a prototype chas sis powered by a production-based but race-modified 1000cc engine.

"I've wanted to do this for a lot of years," said Stanboli, "to get away from all the restrictions we have here in U.S. racing and build what I want. I've been looking at GP bikes as they've evolved over the last several years. I know what to do. I'm see ing a trend to lower cg, the underslung swingarms. Most of the gas will go under the seat." This means that the Attack Performance CRT will not be a "Lego bike" like the ones that brought up the rear in pre-season MotoGP testing and early races. The Lego approach is to buy a 150,000-euro ($196,000) Swiss Suter chas sis and then bootleg BMW, Kawasaki or Honda Superbike kit engines out the back door of some willing Spanish dealer. Stanboli has amply proven he can build engines with the best of them; his Kawasakis won the Daytona 200 in 2007 and 2008. The engine in his current ZX-1OR AMA Pro SuperBike has been dynoed at close to 205 horsepower.

"We'll make one chassis but enough pieces to build at least one more' he said. "We need to get it finished and tested."

Stanboli may be unique here in the U.S. in having the electronics know how, the machining facilities, the famil iarity with CAD-CNC production and the motivation for such a project.

Initially, Stanboli's entry will be based

on the Kawasaki engines he has been running in AMA Pro Road Racing, but he says a BMW engine might be a later choice. This would, he says, be a ride-bywire project using a MoTeC Ml ECU.

"I don't know what all this talk about banning electronics is about," said Stanboli. "Electronics tighten up the field by smoothing things out for com petitors. If today's fighter planes had to be built without their electronics, they'd need four pilots to handle the workload."

Stanboli gave a strong example of how much even a simple traction-control system can compensate for the difficult powerband of a highly tuned engine.

"Back in 2006, Kawasaki brought a new 1000. The chassis was a noodle. The engine made humunguloid torque; it was totally unrideable. Damon Buckmaster was the rider. When we switched-on a simple-rate TC [a trac tion-control system that triggers from the engine's rate of acceleration, not from comparing front-and-rear wheel rpm], he wentfour tenths of a second a lap quicker. It was popping and bang ing everywhere [the system restored traction by cutting cylinders to suppress wheelspin, causing irregular firing]. We'd switch it off and he'd go four tenths of a second slower. Meanwhile, the Yoshimura bike, with a bunch less horsepower in the midrange, was faster around the track."

That four-tenths of a second only seems small. At the end of a 25-lap event, it's 10 seconds.

Experiences like this underlined that control, not raw power, is the real tool for winning races. Old-time dirt trackers knew well that tuning for peaky

max power just killed traction. It took smooth power to hook up and get the drive off corners. The winning team was the one that backed the power down and smoothed it out until the tire hooked up. Tn 1982, Rob Muzzy proved this worked on pavement, too, when the AMA's 1025cc Superbike series was won, not by sprocket-ripping peak power, but by power intentionally smoothed out by dyno development so the rider could apply more of it.

Stanboli knew he had to master the new technology of electronic controls, which is as central to racing today as jets, needles, slides and float valves were to the racing of the 1970s. He became a MoTeC dealer and explored the possibilities of the new medium.

When I asked him what performance level he was planning, he said, "I'm shooting for 15,000 rpm. We put 2000 kilometers on last year's engine, and it made just over 200 hp. If we're aiming at only 3~/2 hours of running time, we can build to 15."

That is the current redline for World Superbike engines. If the engine can be made to pump the same air and burn as well at that level as it did last year at 13,800, the result might be 2 15-220 hp. But Stanboli said his goal for Laguna Seca and Indianapolis was not power but range and the freedom to use gear ing as it is used in MotoGP.

When I asked about suspension, wheels and brakes, Stanboli replied, "I'm looking at all the standard stuff." Too many projects have tried to include radical but unproven technologies. They waste time. The aim here for Stanboli is to race with a U.S-built MotoGP bike.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCharacters In Exile

JULY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAvon 3d Ultra Radial Tires

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupNorton To Tackle Tt

JULY 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1987

JULY 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

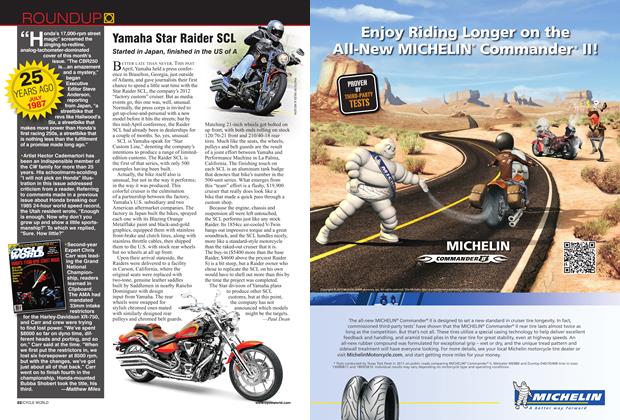

RoundupYamaha Star Raider Scl

JULY 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Claudio Domenicali

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato