House Rules

RACE WATCH

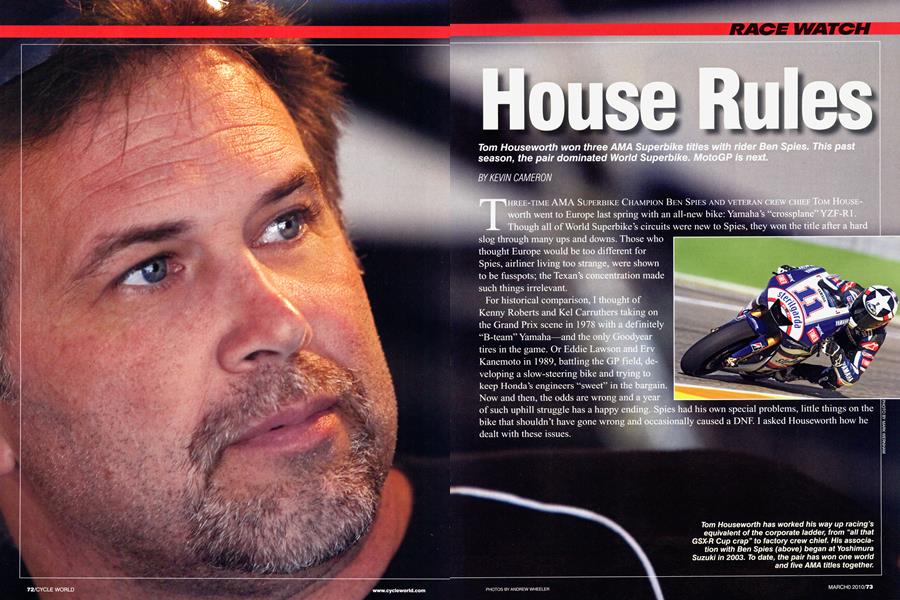

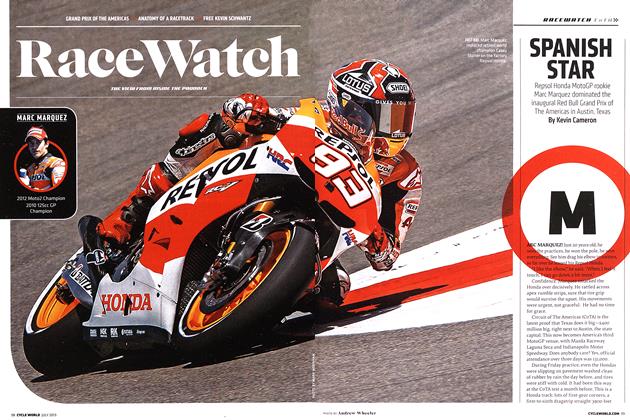

Tom Houseworth won three AMA Superbike titles with rider Ben Spies. This past season, the pair dominated World Superbike MotoGP is next.

KEVIN CAMERON

THREE-TIME AMA SUPERBIKE CHAMPION BEN SPIES AND VETERAN CREW CHIEF TOM HOUSEworth went to Europe last spring with an all-new bike: Yamaha's "crossplane" YZF-R1 Though all of World Superbike's circuits were new to Spies, they won the title after a hard slog through many ups and downs. Those who thought Europe would be too different for Spies, airliner living too strange, were shown to be fusspots; the Texan's concentration made such things irrelevant.

For historical comparison, I thought of Kenny Roberts and Kel Carruthers taking on the Grand Prix scene in 1978 with a definitely “B-team” Yamaha—and the only Goodyear tires in the game. Or Eddie Lawson and Erv Kanemoto in 1989, battling the GP field, developing a slow-steering bike and trying to keep Honda’s engineers “sweet” in the bargain. Now and then, the odds are wrong and a year of such uphill struggle has a happy ending. Spies had his own special problems, little things on the bike that shouldn’t have gone wrong and occasionally caused a DNF. I asked Houseworth how he dealt with these issues.

“After Monza [where Spies ran out of fuel within sight of the finish line], we brought in Woody,” Houseworth began. He was referring to Greg Wood, a chassis technician, who worked for Yoshimura Suzuki from 2004-08. “I knew he’d bring more confidence for Ben—another familiar face. And he could do what I couldn’t. I told him, ‘Don’t leave this bike—ever.’ This caused some wars with our dear friends, the Italians.”

Yamaha’s World Superbike team is based in Italy, and there had been a few “misunderstandings” about changes made to Spies’ bike without discussion or notice. Other riders before Spies—notably five-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan—have had similar problems. Engineers love best of all to test their ideas in a “double-blind” situation in which the rider doesn’t know anything has been changed. A skeptical tire engineer will sometimes send a rider out in the afternoon on a tire that he’s already tested that morning to check the rider’s ability to distinguish; the good ones always can. When the test is unproven hardware or chassis settings, the rider may become angry, viewing this exercise as wasting not only time but time at risk.

How were equipment problems dealt with through the year?

“We had the run of the place,” Houseworth said. “There were some things wrong, and we tried to fix ’em. The team did a lot in-house, and as long as we could show that what we wanted would work, Ben could have any seat height, any handlebar, pretty much whatever he wanted. By the fifth race, he was comfy with a baseline that worked most places.” Houseworth paused, then added, laughing, “But it was still a truck!” >

'Back in ’89, Lawson called his factory NSR500 “the ponderous Honda” because it resisted changing direction; the team worked on that problem through the whole season.

Success in racing is like this: Everyone has problems and has to cope with those problems every practice, every race. The crew makes the bike as good as it can be in the time it has, then the rider has to do the rest by adapting his riding style. Everyone improvises.

“If we had dry practice sessions, Ben would be up to speed in the first session,’ Houseworth said. “But if it rained, the pavement transitions were invisible, and his brake markers were screwed up.”

I asked about Spies’ remarkable ability to learn new circuits quickly and then be competitive and win against men who have ridden those tracks many times before.

“I think he was like that from Day One; that’s not something you can learn,” said Houseworth. “It’s just a talent. At Phillip Island, Ben came in from a practice and said, ‘Wow, that was a rush! I got behind so-and-so and just shut my eyes!”’

Is that the racer’s version of “accelerated learning?”

“Only one other rider I’ve worked with—I’ve been doing this since ’81—had the ability to learn circuits fast like that: Cal Rayborn III,” said Houseworth.

How can a fresh look beat seasons of staring? The usual expectation is that when a rider enters a European-based series, he plans to use the first season to learn the tracks and the life then has a shot at the title the second year. Spies fought at every race and took the title.

I wondered how Houseworth used his experience to help Spies. “I tried to> teach him everything I knew about racing as he was coming up,” he said. “We were figuring it out as we raced. Maybe the watch shows that the first lap was a little slow. We talk about it—what he can do to improve next time. We work on that each time. There is the first step, when the tire grip starts to go a little, and then, near the end of the race, when the tire is really going. He honed it, and I helped where I could. The gains got smaller, but it was the same process.

“We talked about how Mat Mladin would control a race—pulling a gap, managing the tire, always thinking ahead,” Houseworth continued. “Then came the day when Ben had won a few races and he said, ‘Now I know what it means to control the race.’ He’s capable, always thinking three to four laps ahead, about what the tires will do next, what to expect.

“But there was always Haga,” he added.

Noriyuki Haga had been The Flippant One early in his career, crashing big and telling interviewers his training diet was beer. But since then, he has become a serious rider—and very quick.

Haga would pull ahead in points, then Spies would have a success and the balance would shift back to him. Everyone had bad days, but Spies was able to focus so forcefully that he could almost always make headway—an unstoppable force. But Haga was nearly as unstoppable. And he had the benefit of Ducati’s unparalleled knowledge of

this kind of racing, its ever-evolving VTwin and the tracks.

I asked Houseworth about team politics, saying, “I know you have a reputation for not being the most calm, tolerant person in the room.” He laughed. “The age thing helps. When you get to be as old as I am, you don’t have time for that stuff; you go to the person who can help you. I have the full Yamaha business-card collection.”

For decades, Japanese engineers and managers have introduced themselves with their cards, often taking care to explain the chain of command. Everyone in racing has a stack of these cards.

What about the perennial problem of personal burnout-the danger of losing motivation by concentrating so exclu sively on one thing that you become a monomaniac who can't quit but also can't go on?

"You know, that's a really good ques tion," Houseworth replied. "When we were over there, we didn't have our hob bies. I talked my wife's ear off. I have this photography thing [he takes pictures of the sky], and I'm trying to get it set up so I can do it over the Internet.

“Woody restores VWs,” he added. “That was a really tough deal. There you are, with interesting places all around. But it was a two-day trip to Rome. And everything’s expensive. Woody and I lost weight just walking around, checking out different coffees.

It wasn’t easy. We learned how to cook pretty decently!”

I wanted to know how long Houseworth thought racing would hold his interest. Jerry Burgess, currently Valentino Rossi’s engineer, has been at it for 25 years, and Erv Kanemoto put in at least 30.

“I’m not real sure, actually,” he replied. “I told Ben I might be able to do a few more seasons. I’m looking forward to next year.”

This is really the story of a powerful coping process developed by adaptable and highly motivated people, rather than a report of great results from a top rider on top equipment. Every rider, team and manufacturer faces unknowns—a season is like a long sea voyage during which the unexpected is your constant companion. Nothing is certain. The team that best copes with the unexpected, and is “lucky” besides, might win.

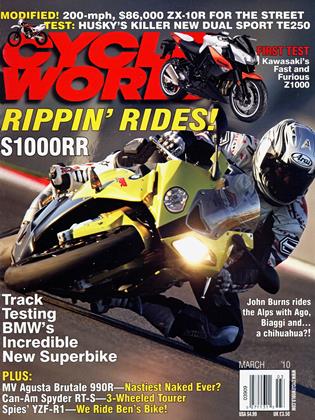

Spies, with Houseworth at his side, now moves to MotoGR He will ride a Yamaha YZR-M1 for the satellite Tech3 team alongside fellow Texan Colin Edwards. In a wildcard ride at the end-of-season round in Valencia, Spain, Spies finished seventh. Not bad for a rank beginner. Can he improve?

“Those guys are quite formidable,” Houseworth said. “But it’s just a motorcycle with the usual problems. Ben will be there.” E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKeeping Focus

MARCH 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAsphaltfighters Stormbringer: Autobahn Extraordinaire

MARCH 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupEddie Lawson: 20 Years Later

MARCH 2010 By Nick Ienatsch -

Roundup

RoundupEtc...

MARCH 2010 -

25 Years Ago March 1985

MARCH 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupBrammo Gains Enertia

MARCH 2010