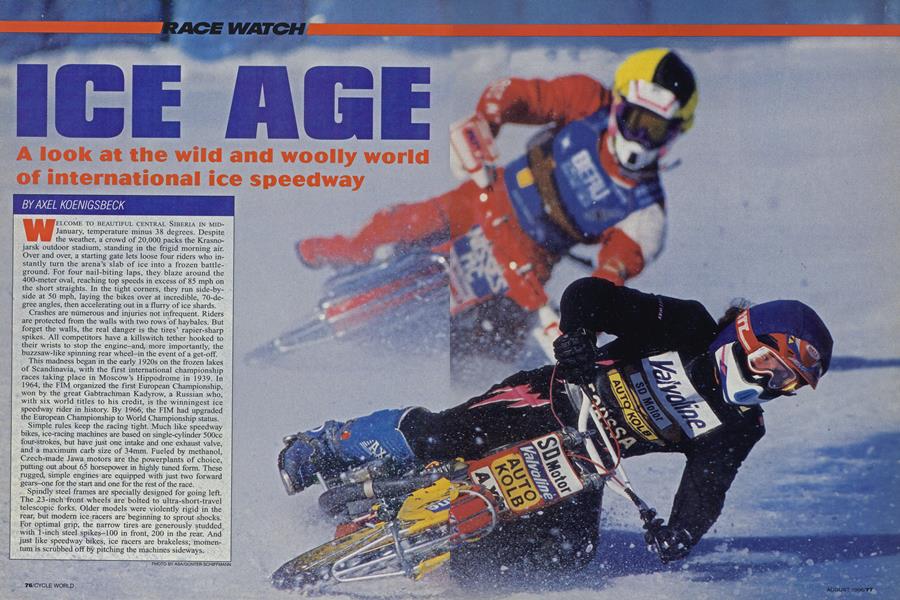

ICE AGE

RACE WATCH

A look at the wild and woolly world of international ice speedway

AXEL KOENIGSBECK

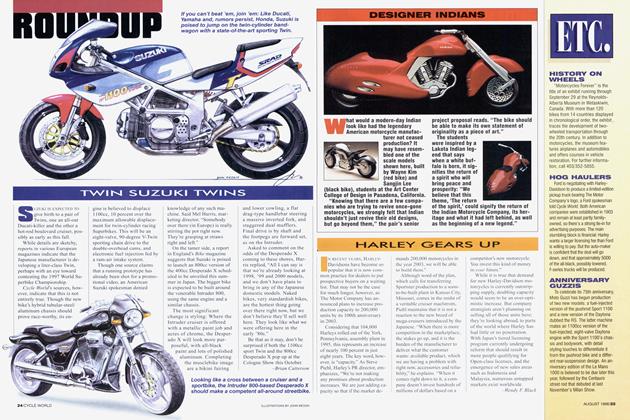

WELCOME TO BEAUTIFUL CENTRAL SIBERIA IN MID-January, temperature minus 38 degrees. Despite the weather, a crowd of 20,000 packs the Krasnojarsk outdoor stadium, standing in the frigid morning air. Over and over, a starting gate lets loose four riders who instantly turn the arena’s slab of ice into a frozen battleground. For four nail-biting laps, they blaze around the 400-meter oval, reaching top speeds in excess of 85 mph on the short straights. In the tight corners, they run side-byside at 50 mph, laying the bikes over at incredible, 70-degree angles, then accelerating out in a flurry of ice shards.

Crashes are numerous and injuries not infrequent. Riders are protected from the walls with two rows of haybales. But forget the walls, the real danger is the tires’ rapier-sharp spikes. All competitors have a killswitch tether hooked to their wrists to stop the engine—and, more importantly, the buzzsaw-like spinning rear wheel-in the event of a get-off.

This madness began in the early 1920s on the frozen lakes of Scandinavia, with the first international championship races taking place in Moscow’s Hippodrome in 1939. In 1964, the FIM organized the first European Championship, won by the great Gabtrachman Kadyrow, a Russian who, with six world titles to his credit, is the winningest ice speedway rider in history. By 1966, the FIM had upgraded the European Championship to World Championship status.

Simple rules keep the racing tight. Much like speedway bikes, ice-racing machines are based on single-cylinder 500cc four-strokes, but have just one intake and one exhaust valve, and a maximum carb size of 34mm. Fueled by methanol, Czech-made Jawa motors are the powerplants of choice, putting out about 65 horsepower in highly tuned form. These rugged, simple engines are equipped with just two forward gears-one for the start and one for the rest of the race.

Spindly steel frames are specially designed for going left. The 23-inch front wheels are bolted to ultra-short-travel telescopic forks. Older models were violently rigid in the rear, but modem ice racers are beginning to sprout shocks. For optimal grip, the narrow tires are generously studded with 1-inch steel spikes—100 in front, 200 in the rear. And just like speedway bikes, ice racers are brakeless; momentum is scrubbed off by pitching the machines sideways.

The 10-race 1996 season progressed from the opening two rounds in Siberia to events in Germany, Poland, Holland and Norway. Russian riders dominated, taking the top five spots in the stand-

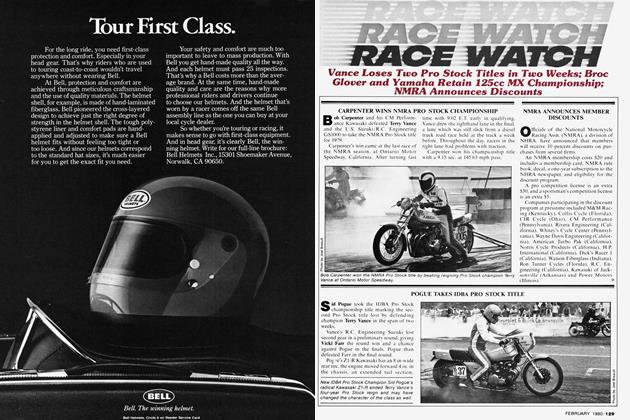

ings. A 28-year-old Moscow resident, Alexander Balashov, led the assault. In 60 heat races, Balashov, the 1994 World Champion, never once parted company with his Jawa. He used consistent finishes to take the points lead after only four rounds. In the remaining six finals, Balashov was unstoppable, winning the title by 59 points.

No doubt, Balashov was helped along by being the lead rider on the sport’s first professional team. Lucky Strike, the same tobacco company that sponsors American Scott Russell in his quest for GP roadracing glory, stepped up this year with full support. Balashov and teammate Vladimir Fadeev, the 1993 World Champion, put the red-and-white-liveried bikes on the podium at every ice GP.

Ice speedway is not a sport for

young, ambitious hotspurs and rookies-the average age of competitors is over 30. In fact, 47-year-old Swede Per Olof Serenius, the 1995 World

Champion, was top European in this year’s series. He won his first title during his 19th season of racing and placed a credible sixth overall this

year. The devoted racer, who is a fireman during the week, says, “I live very much for my routine and benefit from every year in racing.”

Another of this season’s shining stars was Juri Polikarpov, the series runner-up. The 33-year-old Russian is an old-style, give-no-quarter rider-very ambitious and aggressive, he sent several riders, including fellow countrymen, into the fences. Only after his own federation threatened to ban him did he tone down his wild riding.

In addition to the individual title, a World Team Championship, much like the Motocross des Nations, is held each year. With seven national teams competing, the event takes place over two days. This year, the championship was held in Ishevsk, Russia, and guess who walked away the victors? After a three-year dry spell, the Russians took revenge, with Balashov, Fadeev and Igor Jakovlev besting a tough Swedish squad.

Russia’s dominance of this frozen racing art is in some ways a payback for the brutal Siberian winters its competitors must endure. Riders from the former Soviet Union and the current Russian Federation have won 25 of the 31 individual titles since the series’ inception. At one time, ice speedway was Russia’s national sport-like baseball in America. Numerous clubs and leagues existed. But since the fall of communism, the number of active riders has shrunk. Years ago, Russian ice racers started out on state-supported “factory” teams, all expenses paid. Times have changed dramatically: Racers now have to fund their own efforts or sign a contract with the Russian Federation, which pays for travel expenses and machinery, but takes a major part of the rider’s prize money in return.

Unless, of course, Western sponsorship can be obtained. Dutchman Lee van Dam, who is responsible for marketing the series, is excited about the possibility of bringing it to North America. Because the FIM’s broadcast contract with Spanish TV agency DORNA has expired, van Dam is drawing up a new marketing plan for what he sees as an exciting, easily televised sport.

What’s more, van Dam has begun negotiations with American promoters to bring ice bikes to the United States and Canada. "I will fly to America soon and talk with several people who are interested," he says. "There are five venues we're looking at, includ ing the Olympic ice course at Lake Placid, New York." A set of test matches are planned for autumn this year. If these are success ful, an American round could be put on the calendar as soon as 1998. USGP on ice, anyone?

Axe! Koenigsbeck, 43, is a dentist at the University of Düsseldorf In his spare time, he rides sidecars and covers ice racing for European maga zines. This is his first story for Cycle World. Additional reporting provided

Thomas Schiffner

View Full Issue

View Full Issue