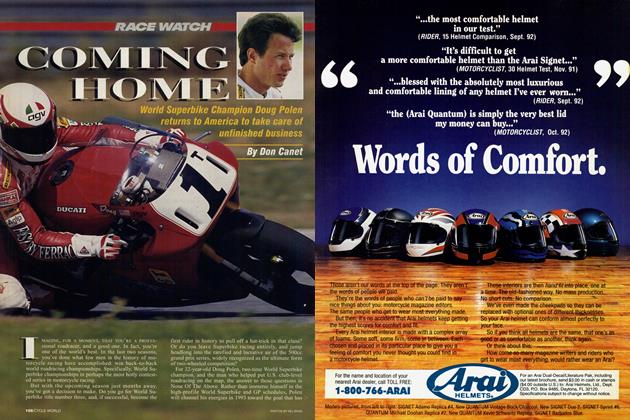

RACE WATCH

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

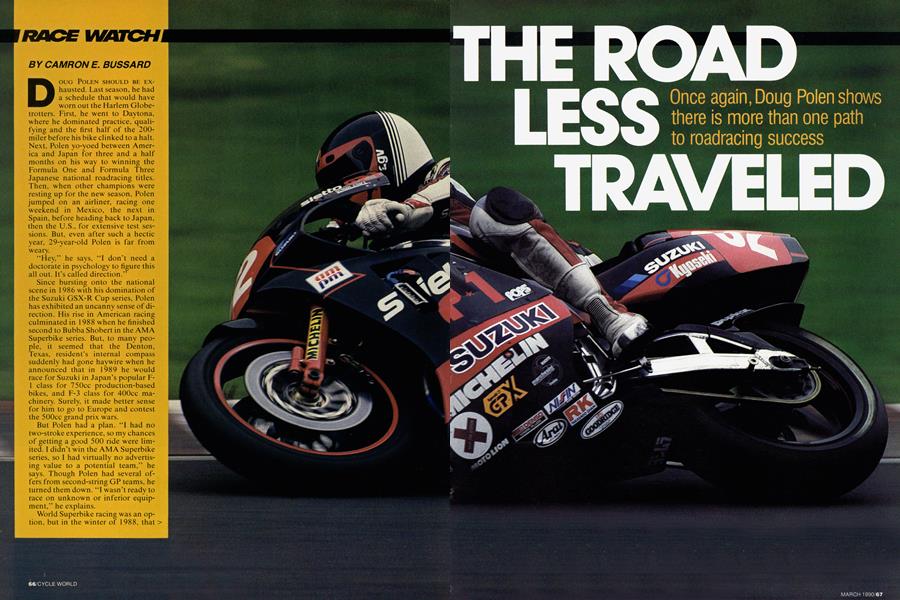

DOUG POLEN SHOULD BE EXhausted. Last season, he had a schedule that would have worn out the Harlem Globetrotters. First, he went to Daytona, where he dominated practice, qualifying and the first half of the 200-miler before his bike clinked to a halt. Next, Polen yo-yoed between America and Japan for three and a half months on his way to winning the Formula One and Formula Three Japanese national roadracing titles. Then, when other champions were resting up for the new season, Polen jumped on an airliner, racing one weekend in Mexico, the next in Spain, before heading back to Japan. then the U.S., for extensive test sessions. But, even after such a hectic year, 29-year-old Polen is far from weary.

“Hey,” he says, “I don’t need a doctorate in psychology to figure this all out. It’s called direction.”

Since bursting onto the national scene in 1986 with his domination of the Suzuki GSX-R Cup series, Polen has exhibited an uncanny sense of direction. His rise in American racing culminated in 1988 when he finished second to Bubba Shobert in the AMA Superbike series. But, to many people, it seemed that the Denton, Texas, resident’s internal compass suddenly had gone haywire when he announced that in 1989 he would race for Suzuki in Japan’s popular F1 class for 750cc production-based bikes, and F-3 class for 400cc machinery. Surely, it made better sense for him to go to Europe and contest the 500cc grand prix wars.

But Polen had a plan. “I had no two-stroke experience, so my chances of getting a good 500 ride were limited. I didn’t win the AMA Superbike series, so I had virtually no advertising value to a potential team,” he says. Though Polen had several offers from second-string GP teams, he turned them down. “I wasn’t ready to race on unknown or inferior equipment,” he explains.

World Superbike racing was an option, but in the winter of 1988, that > series was going through a tumultuous time. When several sponsors backed out of the series, it looked like it would not get off the ground, so Polen declined offers there.

THE ROAD LESS TRAVELED

Once agin, Doug Polen shows there is more than one path to roadracing success

That left Japan. At first, Polen was accused of heading for a season of easy pickings against allegedly slower riders. But as he proved here in the States, Polen is more than a fast roadracer: He’s a shrewd businessman who knows the value of self promotion.

“I thought it (racing in Japan) would be interesting because no American had ever done that before,” he says. “Besides, I would be the foreign rider in Japan, and that would get a lot of attention around the world. Also, the Japanese companies would get to see me race all season right under their noses. It was a great chance to show my portfolio as a rider.”

That recognition was a powerful incentive to Polen, because he believed that his riding talent would not only earn him an esteemed championship or two, but would also give him the kind of exposure he would need to land a top-flight GP ride. “I thought no matter how it turned out in Japan, because of more media exposure, I would be in a better position for a GP ride after a season in Japan,” he says. Getting a GP ride is an important career move because, Polen says, “Everybody still believes GP racing is what it’s all about.”

Should his season in Japan lead to a world-championship ride, it'll come as no surprise to Polen, who seems to take pleasure from using the lesstraveled path to racing success. “Eve always made it a point to do things my way,” he says. “When the Suzuki Cup first started, no one thought about doing it for a living. I did, and made over $90,000 in 1986. Today, everybody wants to do that. Now, some American riders are talking about following me to Japan. It feels great to open the doors on something new and different."

If some of the top Americans manage to get a factory ride in Japan, Polen warns that they should not expect success to come easily. “There is world-class competition over there," he explains. “I raced as hard as I could all season long. The F-1 class is not second-class compared with the 500 GPs, it’s just a different kind of factory racing.”

Japanese F-l bikes must use production-based 750cc engines, but, for the most part, the sky is the limit on everything else. His Suzuki, says Polen, was “the best equipment the factory could develop." It had to be, because all the manufacturers want victories in the prestigious F-l races. Says Polen, “The factories are so competitive that each race every bike is better and faster than the last time out. If you don’t improve the bike, you can’t make up in rider talent enough to stay on top. You can be the best rider in the class, but it’s still hard to beat better bikes."

Polen should know. He was locked in a season-long battle for the championship that went down to the last race. He entered that race with a sixpoint lead over Honda rider Shoji Miyazaki. Polen qualified fastest, but at the start of the race was shoved to the outside of the course by what some observers later called the kamakazi tactics of some Honda riders. Typically, Polen says of the incident that it was “just racing." He went on to set the fastest lap time of the day while cutting through traffic to finish in fifth, which gave him the championship with two points to spare.

Winning the Formula Three championship was not as dramatic. Polen and his GSX-R400-based racebike cake-walked to the championship, further enhancing his image with factory brass and Japanese fans. In Japan, 400s are immensely popular, ^with as many as 600 entries in the 400cc production support classes that are run in conjunction with the F-l and F-3 races.

With the two Japanese championships under his belt, Polen has been considering possibilities for next season. Several GP teams are trying to get him to come to Europe, and world Superbike racing also has some interested parties. But Polen is taking his time, and is being typically cautious about his decision. While he’d love to have a shot at GP glory, Polen will only go to Europe when he feels conditions are right. And he doesn’t suffer from the pressure of measuring up against the current world stars.

‘T don’t need to run head-to-head with those guys to prove I’m as fast as they are,” he says confidently. “When we race at the Suzuka Eight Hour (on four-stroke 750s), our times are about the same, so I know Em in the same league they are.”

Confident though he may be, Polen also is a realist, and knows that to run with Lawson, Rainey and Schwantz, he’ll need front-line equipment. If that doesn’t come, he’ll race in other series. “I’m not about to sacrifice my career for a GP ride,” he says.

It all comes back to direction. If Polen does race GPs, it will be on his terms, after he’s explored all his options. The man who rose from the ranks of amateur roadracing to become one of the sport’s most-professional riders knows where he is now and where he wants to be. “I’d like to be able to race for a few more years,” he says. “And when I look back on my career, I’d like to think people will remember me as someone who showed them a different way to approach racing.”

And, he might add, a different way to become a winner. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue