ROBERTS DISARMED

RACE WATCH

What the hell’s happened to KRJR?

KEVIN CAMERON

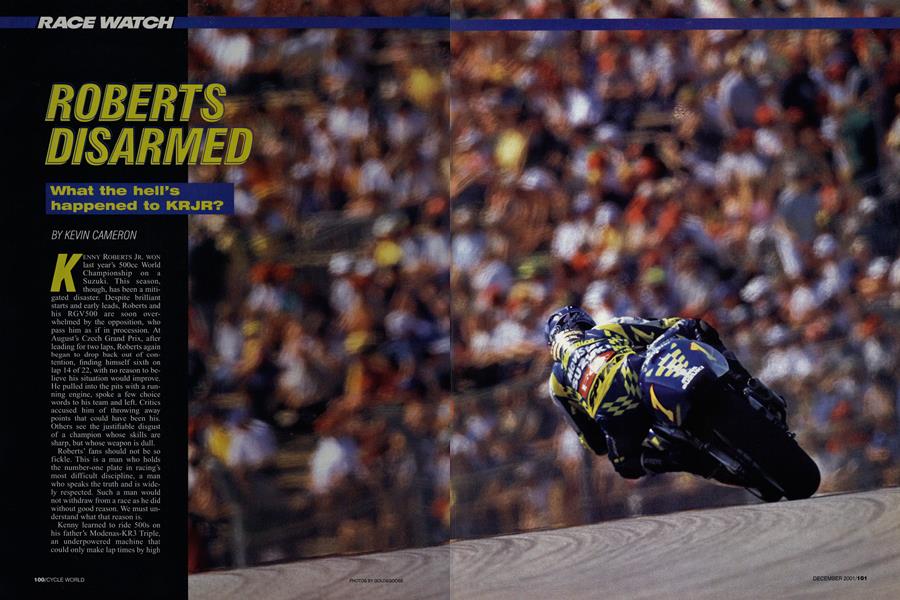

KENNY ROBERTS JR. WON last year’s 500cc World Championship on a Suzuki. This season, though, has been a mitigated disaster. Despite brilliant starts and early leads, Roberts and his RGV500 are soon overwhelmed by the opposition, who pass him as if in procession. At August’s Czech Grand Prix, after leading for two laps, Roberts again began to drop back out of contention, finding himself sixth on lap 14 of 22, with no reason to believe his situation would improve. He pulled into the pits with a running engine, spoke a few choice words to his team and left. Critics accused him of throwing away points that could have been his. Others see the justifiable disgust of a champion whose skills are sharp, but whose weapon is dull.

Roberts’ fans should not be so fickle. This is a man who holds the number-one plate in racing’s most difficult discipline, a man who speaks the truth and is widely respected. Such a man would not withdraw from a race as he did without good reason. We must understand what that reason is.

Kenny learned to ride 500s on his father’s Modenas-KR3 Triple, an underpowered machine that could only make lap times by high corner speed, as it lacked the acceleration of its four-cylinder competition. As it turns out, although this was counter to Kenny’s preferred tail-out riding style, it was superb preparation for riding the also-underpowered Suzuki V-Four.

In his first season on the Suzuki, Roberts won four GPs. How could that be, if it was already down on power? First, Honda was still reeling from the sudden injuries and eventual retirement of five-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan. Second, its engineers put on a hurried rush to push through rash developments Doohan had vetoed. Roberts had to ride the Suzuki as he had ridden the KR3-making a break at the start and then lapping on corner speed. If a rider on a fourcylinder Honda or Yamaha got away first at the start, his lower corner speed would block Roberts’ Suzuki, then pull away on superior acceleration in the drag race to the next corner.

There’s already a name for this problem: It is called “The Twins Syndrome.” When Honda built its NSR500Y it was hoped that the V-Twin’s expected higher comer speed might allow it to lap faster than Foursbut only if it could get away first at the start. When its tires began to lose properties after a few laps, it would lose corner speed and be overcome by the V-Fours.

Critics of Roberts’ action in pulling out of the Czech GP point out that his teammate, Sete Gibernau, is now able to lap consistently, turning decent times, through whole races. Why can’t Roberts do this? The obvious answer is that the champion is expected to win races, not gracefully settle for ninth as Gibernau did at Brno. Racers race, so Roberts gets the best start he can, tries to get away as he did in the 2000 season and, when the attempt fatigues his rear tire, fades from the front. Which has the greater appeal, reaching for the top or sitting comfortably two-thirds of the way up?

The team was frustrated even before the season began, for there was a feeling that testing was going poorly and that the others had pulled farther ahead. Bud Aksland, cylinder-andpipe-development engineer for the Proton-KR3 team, said, “Yamaha is spending an incredible amount of money on racing. And Honda is Honda.”

Meanwhile, as we see from the recent Suzuki/Kawasaki alliance, the days of generous development money are, at least for the moment, over. Suzuki faces a real problem in maintaining the competitiveness of its twostroke 500 while simultaneously developing its XR-E0 four-stroke GP bike. Despite this, Suzuki had the only complete engine makeover in the 500cc class this year, with an enlarged crankcase and revised transfer ports.

Those who interest themselves in such matters say that the Suzuki RGV500 is a very complex machine, with both guillotine exhaust gates and exhaust pipe resonator chambers.

“Lots of parts. Band-Aids,” said another insider, adding that development is moving up a dead-end street of “more compression, more ignition timing and higher exhaust ports.” All these actions

attempt to squeeze the engine’s fresh charge harder, not to increase power by pumping more of it. Ultimately, they increase the engine’s fragility faster than they do its power. And it’s still down on both acceleration and bhp.

Can it be that Suzuki is continuing to develop the same kind of narrow-power porting it used for the first 10 years of its participation in 500cc GP racing? We know that companies like to “confirm their individuality” by adhering to fixed design ideas like single-sided swingarms, so there is a precedent for this. Other evidence is supplied by the fact that the Suzuki is a heavy drinker-using more than the usual 6.8 gallons of fuel over a race distance. Heavy consumption in a two-stroke is a symptom of short-circuiting-the direct loss of fresh charge out the exhaust port before it can be trapped, compressed and burned to make power. Porting of the type Suzuki used to use in its 500s has this characteristic-good cylinderfilling occurs only within a narrow rpm range up high. Below that, the mixture has time to reach the exhaust ports and be lost.

You’d expect such midrange charge loss to produce a weak midrange, and that, too, is a characteristic of the current Suzuki, and is the primary cause of its “Twins Syndrome.”

An engine with weak midrange has a stronger “hit” than does an engine with a wide powerband. That is, torque rises extrasteeply as the engine accelerates out of its midrange and into its solid power. Early in a race, the rear tire-especially a 16.5-incher-has the grip to make this transition during acceleration without surprising the rider with sudden wheelspin and sideslip. As the tire ages and loses its peak grip over five to 10 laps, the steep powerband and the wheelspin it threatens become an actual danger to the rider.

Riders talk a lot about “throttle connection.” Roberts says the Suzuki has poor throttle connection, but what does that mean? “When you turn the throttle half a degree,” Aksland explained, “you want to get half a degree’s worth of response from the engine.”

Roberts has to turn the throttle too far to get his bike to accelerate, and then as the engine revs into its real power, he’s having to quickly roll off again to keep the tire from spinning up. He is a human traction-control system.

Conversely, riders praise the Honda’s throttle connection-if the tire’s spinning up, you can roll it off just a notch and it hooks right up. If you want a little more, you dial it on. Call it “linear throttle response.”

The value of this is shown by recent developments in four-stroke GP bike engines. At first, both Honda and Yamaha announced 225 horsepower (Honda’s goal is 248 bhp for next spring!), because engineers naturally exploit the variables with which they are given to work. Tuner Erv Kanemoto noted that last spring Yamaha took a new design direction. Was it a radical new powerproducing scheme? Just the opposite. By notching back to 190 bhp and giving the engine a superwide, dirt-track-style powerband, engineer Masakazu Shiohara was able to create that most desirable of all roadrace machines-the docile streetbike with Grand Prix top end. Although the engine revs to 15,000 rpm, its torque peak is given down near 8000just above 50 percent of peak revs. This is similar to a Harley-Davidson XR750 dirttrack engine, whose peak torque comes at 5500 rpm,

but revs to 9300. Compare this with conventional four-cylinder roadrace engines, whose torque peaks at as little as 1500 revs below the power peak. The easy usability of the new Yamaha’s wide torque gives a rider the best tool for going fast-free of surprise flat spots and tricky torque jumps. This is why the YZR-M1 was able to run a racedistance test at Brno 40 seconds quicker than the current record. That is throttle connection.

Whatever the reason for Suzuki’s present 500cc plight, attempts at a fix have brought mixed results. During the mid-season break, a pre-Big-Bang engine was tested at Mugello. It sacrificed acceleration and top speed for a better throttle connection, so that Roberts could open the throttle at the same points as other riders. Even so, with the overall performance deficit, he was still forced to make lap times from corner speed, a proven trap.

Tires are another issue. When the 16.5-inch rear was introduced, riders noted that it steered heavily but maintained its grip longer than the more precise-steering 17-inch of the same rolling radius. The heaviness arises from the 16.5’s larger footprint, which more strongly resists being turned on the ground. That larger footprint also produces more, longer-lasting grip. Because the 16.5’s turning delay requires more time leaned over in a given corner, it forces the Suzuki into a longer part-throttle situation in which its powerband puts it at a unique disadvantage. With the 17, the bike could come upright sooner, the throttle open farther. Yet the 16.5 also had the advantage of masking better and longer the hard hit when the power came on. There was no right answer in tires.

Think of the frustration. At the second GP in South Africa, Roberts got the break and led 12 laps. The rest of the field accumulated behind him, at first unable to pass. When his tire fatigued, around him they went. The fourth race was the French GP where, again, Roberts got the break and led. And again, as everyone’s tires fatigued, the effect on the Suzuki was the greatest and the others passed him.

So the season has gone. The harder Roberts has tried, the sooner his problems have surfaced, pushing him to the rear. Gibernau, with perhaps different professional priorities, has achieved a kind of consistency. Years ago, I was present at a trackside discussion in which a Japanese engineer made the following incredible declaration: “Rider not ride so hard, then machine better, also result better.” Sorry, this isn’t what racers do, and if Roberts had pulled his punches that way in 2000, he wouldn’t be the world champion. Again, racers race. The engineer’s job is to keep the motorcycle out of the rider’s way, but as they used to say at NASA, “No bucks, no Buck Rogers.” When cash permits, development explores multiple pathways. For the moment, a smaller company can afford only one path, and for Suzuki, it happens to be the wrong one. Backing up to find a better way is almost impossible within a racing season.

Kanemoto believes Suzuki will quickly find its way again with its four-stroke, which is planned for a 2003 introduction. As Honda and Yamaha prepare for the dawn of 990cc four-stroke GP racing next spring, Suzuki’s plan calls for one more year with the 500cc two-stroke. This past September, Roberts released a statement. It read: “Brno was the peak of frustration that has been building up all season. My actions were a cry for help-everything else I have done before has not had any results.”

Suzuki higher management has since promised Roberts that, “Next year, Suzuki will have the most competitive bike on the track-two-stroke or four-stroke.”

Roberts’ statement ends, “It’s all behind me now and I want to go forward, with the hope of winning the World Championship with Suzuki again next season.”

Good luck.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWind Machine

December 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Ducks

December 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAnyone Can Do It

December 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupMerger Mayhem In Japan

December 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupIs Saddleback Back?

December 2001 By Brian Catterson