Return to Road Atlanta

RACE WATCH

Witnessing the future of American roadracing

KEVIN CAMERON

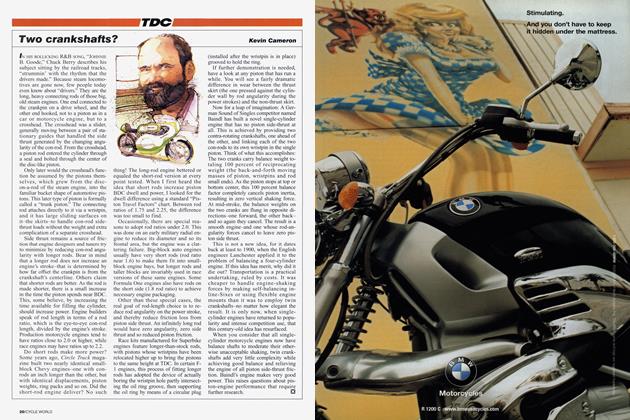

THE DELTA 737 THAT CARRIED ME AWAY FROM ATLANTA WAS banged hard from side-to-side by the same gusts that had made the weekend’s racing at nearby Road Atlanta so strange. In Saturday’s AMA Pro SuperBike Race 1, closely matched Josh Hayes and Blake Young had touched, wrenching the handlebars out of Young’s hands and dumping him on the track to slide it out. His Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R1000 continued upright, crashing once on the grass. After a red flag and the subsequent restart, Young came from last to win, the two men trading the lead as dramatically as before. It was electrifying. What would Sunday bring?

It brought a stunning 1:24.922 lap by Graves Yamaha YZF-R1-rnounted Hayes, faster than his qualifying lap. Young was blown off the track by a wind gust on about Lap 3, and of his eventual secondplace finish later said, "I just wasn't all th~ motivated after that." Attack Performance' Steve Rapp had a similar experience, his Kawasaki ZX-IOR's top speed dropping from around 180 mph to 169. I asked Hayes, "Does the wind not blow on you?" He laughed and said, "I'v ridden bikes that were really affected by gusts, but for some reason, this one isn't. Background'? Hayes's Yamaha is faster this year. Young's crew chief, Peter Doylc said, "Last year, the Yamaha accelerated really well, but then went kind of flat. Now, they are stronger on top. They've got three, four miles per hour." But when Young had his mojo work-

ing, it didn't matter. He and Hayes went `round and `round, one passing on the inside, the other slipping under him as he went wide from his faster entry. This was action as hot as the famous Valentino Rossi/Jorge Lorenzo battle of 2009 at the Circuit de Catalunya in Barcelona, Spain. The Yamaha's touch of braking instability was an added test for the steely Hayes. With Sunday's win, Hayes was crowned the "Big Kahuna" of the weekend, the first race weekend of the Big Kahuna Triple Crown. Doyle referred to a fairing controversy, saying that when the rules limit power, yon must waste less. In Yamaha's case, that might mean narrowing the fairing. Were they "caught and fined" for doing so? In any case, the lower-drag fairing was homologated at the next event. How does this work? Search me, bud, but the background chat says, “Yamaha cooperated with the Daytona Motorsports Group from the start, while early DMG leadership regarded the other factories—Suzuki and Mat Mladin, in particular—as an evil empire too long in power that had to be defeated and driven out of the sport.” Does that mean favoritism? Certainly not. Every official in a position of public trust is impartial, right? Then, some ask if Yoshimura’s fairing has had its intake “nostrils” moved closer together—nearer to the stagnation point of maximum pressure on the nose—to maximize intake ram.

What does it come down to? It sounds to me like lawyers quoting rules, making points-of-order, objecting. Yes, it’s always part of the game. Rob Muzzy protested all of Suzuki’s Supersport entries for cam phase in the late 1980s, and Bob Hansen protested the Suzukis for finless heads in 1972—both cases right here at Road Atlanta.

I counted 28 tractor-trailer combinations. Three were owned by Dunlop and two by the AMA, and the estimate was that there were almost twice as many as last time here in 2010. Advance ticket sales, stimulated by Ml PowerSports, were said to be “very satisfactory.” During the pit walk, there was a heartening press of families—children gathered autographs on posters while their parents took pictures and looked pleased. All weekend, an airplane towed a Geico insurance banner overhead. At the end, the exit roadway was solid cars for a long time. I was pleased. I don’t want to think motorcycling was a one-time, nonrecurring phenomenon of the 1970s.

What about all the beautifully painted, tricked-out-but-slow Yamaha TZ750s I’d seen from 1974 to 1984? Money is more common in paddocks than quick laptimes. Some new big-truck teams won’t get what they want because they don’t know what to do. I thought of racerturned-journalist Dennis Noyes’ remark that “The fast Moto2 teams all have one thing in common: a top crew chief.” Up and down pit wall, I saw people adjusting things and staring at laptops, but when racing started, the same three or four riders pulled away. Rules can try to slow the fast teams, but the machine and its support equipment are just the violin; there’s no music until rider and crew learn to play it.

Now, for the first time since the disastrous DMG revolution in AMA Pro Racing several years ago, I feel there is serious progress back toward a successful series. Technical Director of Competition Al Ludington (for many years, he was crew chief for Miguel Duhamel, the winningest rider in AMA roadracing history) explained what they are doing.

“I look at our classes as stepping stones,” he said. “SuperSport is for beginning riders and teams. We allow traction control there because it’s now so cheap, but that’s it on the electronics. Riders learn to ride, and teams learn to make their bikes into better tools. Then, we have Daytona SportBike, which is more advanced; we have a $7500 cap on electronics there. Riders who have learned what SuperSport has to teach them now have to deal with more power and more tuning options. If they’re hoping to move on into professional racing, they’ll have to leam that stuff. And then, we have SuperBike. We’ve essentially said, ‘Everything from the head gasket down has to be stock,’ but we leave things like head porting to the skill and imagination of the teams that have come this far.” Earlier, I’d seen what today’s learning process is. AMA newcomer Colter Dimick from Fort Collins, Colorado, was working with Kinelogix’s Kamal Amer to bring his SuperSport lap times down. After each practice, Amer would pull a memory chip out of the bike’s dash—a chip just like those in today’s cameras. These chips have huge capacity, so data from the bike is tiny by comparison. Amer showed me a three-axis accelerometer, taken from a video-game controller, that can report the machine’s attitude, rate of acceleration and distance traveled—all without expensive suspension or wheel-speed sensors.

“I can buy these for $12.95,” said Amer. His strategy was to look for those places on the track where Dimick’s performance was inconsistent, indicating the rider wasn’t sure of a best strategy or that marginal control was scaring him. Dimick had dropped 5.6 seconds in lap time from Friday to Saturday. Amer pulled up another problem area, where there was 0.8 of a second between his best and worst laps.

“What’s going on here?” asked Amer, tapping the computer screen. Dimick’s hands began to move back and forth on imaginary handlebars, indicating in the age-old language of racing that steering was becoming uncertain.

“I’m coming over the crest of a hill,” said Dimick, “so the bike’s getting light.” He thought some more. “But the next corner’s coming up, so I need to get on the brakes. But when I do, there’s no grip yet, so the bike’s all over the place.”

This is the same process I saw top riders using in the 1970s—doing a block of laps, then coming in to analyze them, identify problem areas and find answers. I remembered Mike Baldwin in his lawnchair, concentrating for 20 solid minutes after a seven-lap practice. Or Kenny Roberts at Brands Hatch in 1974, going up into the tire truck to think for three hours. Today, with electronic data collection, it’s much easier to locate problems, analyze and plot solutions.

Dimick was doing exactly what Ludington described to me as the AMA’s goal: learning racecraft so he can move up. He would finish 15th in both SuperSport races out of 43 entrants.

I can hear the complaints already.

“Oh, the top teams have GPS, so they can set anti-wheelie and anti-spin corner by corner, but the little guy...”

Attack Performance’s Richard Stanboli, crew chief for Rapp, said, No one suggests penalizing teams for having intelligence, a heavy sponsor or sharp engine builder. Every team needs and wants those. The debate rages nevertheless. British Superbike allows more trick hardware on the bikes but essentially bans electronics.

John Ulrich, a team owner since 1980 and publisher of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology, wants more controls on electronics, holding up the spectre of “$300,000-a-year software writers” creating secret dominance despite AMA’s planned 2013 $18,000

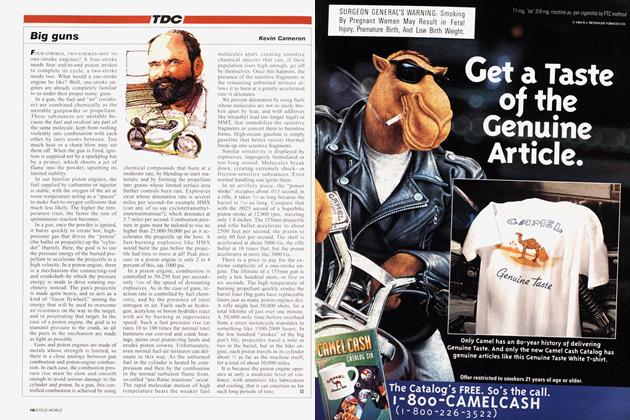

Two Yamahas, a pair of Suzukis, a Buell and a Kawasaki lead SuperBike (above left). Expectations are high for Chris Fillmore (above). The former supermoto star pushed hard all weekend, knocking big chunks off his lap times. He finished sixth in Racing could ban anything it likes, but manufacturers adopt electronics as original equipment because it’s the cheapest way to do what needs doing. Eyes were on DSB Race 1 because the Team Latus Triumph 675 Triple that had come so close to winning at

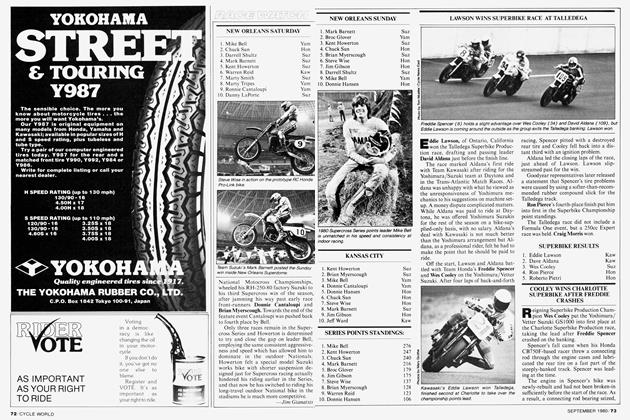

Daytona was on the line with the usual 600cc four-cylinder suspects. But rider Jason DiSalvo fried a clutch. Builder Ronnie Saner said, “We have a really tall first gear in this [Road Atlanta needs close-to-Daytona gearing], and it takes some patience to get it moving. After the start, the clutch stack expands, and the [clutch] lever gets bowstringtight.” Martin Cardenas, Ulrich’s star rider, won both DSB races. In the second race, DiSalvo ran third for 11 laps, then slowed with an oil issue. Saner is very “up” about working with Triumph because “It’s a smaller company, and everyone is so enthusiastic.” When some of Stanboli’s Kawasaki engines broke cranks many years ago, he sent

them to a metallurgist. The verdict: “These are nicely hardened on all the journals. In a street engine, they should last a million miles. But inside, they’re pudding.” EBR stands for Erik Buell Racing, which is collaborating with the Indian manufacturer Hero Motor. How did Buell rise from the ashes after HarleyDavidson closed the division? Pure “That’s easy, and you don’t need GPS. You just write a little software that sums how far the tires roll; that tells you what part of the track you’re on. And sure there’s error, but you take that out by rezeroing each time you get the transponder pulse at start/finish.” energy! Hero started out making smaller Honda models but is now independent. Its engineers burn to show what they can do. Two were at Road Atlanta, and there are seven more back at Buell’s factory in East Troy, Wisconsin. The 1190 EBRs were loud, and rider Geoff May (Road Atlanta is his home track) headed up a train of alternative brands in SuperBike Race 1. He was fifth ahead of Chris Fillmore on a KTM and Rapp on Attack’s privately backed Kawasaki ZX-10R. May ran fifth again in SuperBike Race 2 on Sunday, only to pull in with a loose shifter. The EBRs are essentially non-electronic bikes now, but a “Marelli-ed-up” version is in the works—Western technology, Asian money and ambition.

What’s happening in AMA SuperBike now is right and proper. The two teams up front—Yamaha with Hayes and class-rookie Josh Herrin, and Yoshimura Suzuki with Young—are the teams that stayed despite DMG’s early and mistaken effort to “drive out the factories.” Honda and Kawasaki are still out, but taking their places are newcomers EBR and KTM, working to earn their way forward, not relying on preferential rules to do that work for them.

What about Ducati? I asked Ludington which model would be eligible for AMA SuperBike homologation. “The Panigale, most likely,” he replied.

Ducati enthusiasts would love to see the new 1199 raced here, but success requires more than good intentions and January hiring for a March Daytona debut. We can hope there’s something in the making.

Just as we are seeing in Moto2 and the new Claiming Rule Teams (CRT) bikes of MotoGP, there is no “Lego bike” that you can snap together and run up front. Some of the “big-truck teams” have everything but results. Learning takes time, and we hope they stay the course. Weird things happen that aren’t covered in the owner’s manual. Stanboli told of oil accumulating in the airbox. “You see the bellmouths wet with oil,” he said. “You turn the engine upside-down, then upright again, and all that oil runs back to the sump.”

Details: clutches that swell, oil that hides itself, cranks made of pudding. Only experience equips teams to deal with such things. Experience takes time, so I hope the AMA’s “steppingstones” system trains riders and crew as planned, to fill out SuperBike and keep up the exciting racing we saw at Road Atlanta. It’s looking good.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

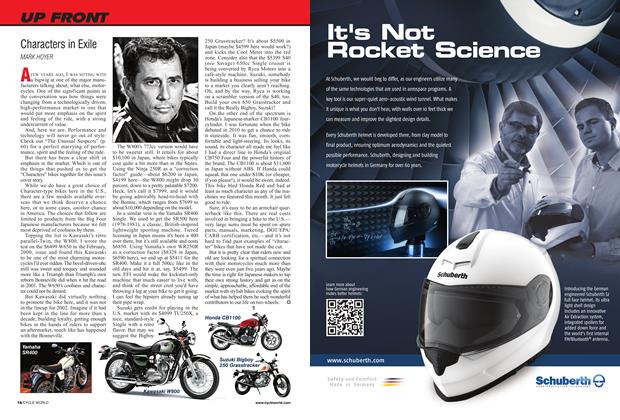

Up FrontCharacters In Exile

JULY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAvon 3d Ultra Radial Tires

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupNorton To Tackle Tt

JULY 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1987

JULY 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

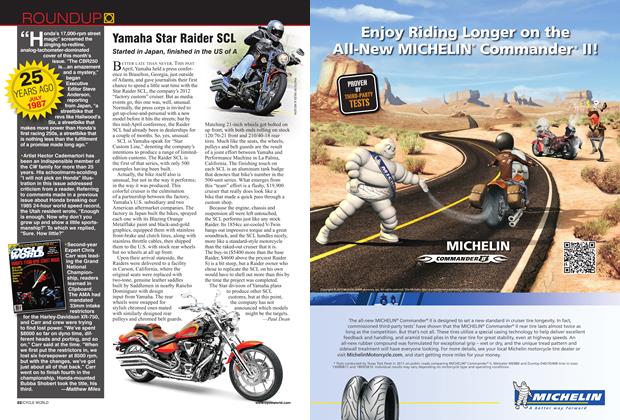

RoundupYamaha Star Raider Scl

JULY 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Claudio Domenicali

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato