Keen Observations

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

By 1967, INTENSIVE DEVELOPMENT performed by Doug Hele's team at Meriden had made high-revving 500cc Triumph Twins dominant in what there was of U.S. roadracing. Output had reached 48-and-something horsepower, and the great big, old-technology Harley KR flathead 750s—even with just over 50 hp to push their bulk—were nowhere.

Yes, that's right: 750cc. AMA rules in those days held overhead-valve engines to 500cc while ivin~ flatheads 750.

That difference made sense. To get air into a flathead, it had to first pass through the horizontal carburetor bore then turn almost 90 degrees to flow up to the underside of the intake valve. In flatheads, instead of the valves being above the piston with their stems pointing up, they were beside the piston in a side extension of the combustion chamber, with stems pointing down. At the valve, the air had to turn sideways again to flow out of the side chamber in which the two valve heads sat, then continue sideways, out over the piston and turn downward to follow it on its intake downstroke. That is most of three 90-degree turns, and even with great big ports, it wasn't easy. As airflow guru Kenny Augustine says, "You can make air go fast and you can make it go around corners, hut you can't do both at once."

Air goes into an overhead-valve engine much more easily; there is just one turn down at the intake valve

Then, suddenly, in the spring of 1968, the Harleys were uncatchably fast, and it was essentially all over for the 500 Triumph. The flatheads had somehow risen to a whole new level-lOto 15mph faster in qualifying than the fastest Triumnhs.

The usual explanation is that Harley's new "Cal Tech wind-tunnel fairing" and dual Tillotson diaphragm carburetors were responsible. But there's more-a lot more.

One day last fall, I received an e-mail explaining this. The narrative comes from veteran dirt-tracker and frame desi~ner Neil Keen.

"One Sunday, we took Henry Hawks' KR over to C.R. Axtell's to run it on his dyno. I said to Ax, `Have you noticed how all the truly great flatheads look pretty similar but they don't look anything like these things?"

Keen was thinking of what he'd seen in the flathead chambers of Graham, Auburn and Hudson auto engines. "I said, `I think the restriction in the engines is the airflow hitting the heads and not the nnrts'

"Axtell, being an old flathead-Ford, dry-lakes guy, knew exactly what I meant almost before I got through saying it. Ax said, `I have been thinking about that same thing. Let's just try something. Let's make some quarter inch he~i iaskets"

What Keen and Axtell were talking about was the fact that in a flathead, the valve side chamber had both airflow and combustion-chamber functions. They were thinking there was a bad compromise between compression ratio and flow. For best flow, the valve chamber needed to be big and smoothly shaped, but that would lower both the compression ratio and engine torque. For high compression, it had to be low, tieht ani cramnv restrictine the flnw

Axtell's idea of quarter-inch head gaskets was to lift the heads up on quarter inch spacers to see if that improved the flow.

To cut the inside shape of the spacers, Keen drilled a three-quarter-inch hole through the quarter-inch blank, threaded a length of bandsaw blade through it, butt-welded the ends, put it on the saw and cut the inside shape. Then, he broke the blade to get it out. "When we put one [of the gaskets] on a cylinder with the head and flowed it, airflow increased almost 50 percent."

"Then Ax said, `Let's run it and see what hannens.'

"I said, `Hell, Ax, it ain't got even threeto-one compression now!' Axtell said, `Well, let's just try it." When they did, it produced just as much power as before, despite the huge drop in compression ratio. The extra airflow produced by getting the head out of the way of the flow from the valves had made up the difference.

"I said, `All you have to do now is start filling in with clay `til it hurts the airflow, right?' Axtell put the clay everywhere and in two days got the ball rolling.

"Then he called Harley race manager Dick O'Brien, who made a date to come out straight away. Brought Roy Bockelman with him. Ax had shrunk the ports more than a quarter of an inch [a reduction of cross-section of 30 percent]. Then they went back home to Milwaukee, and Roy brazed up the ports and welded up the crowns on a pair of pistons and remachined some blank heads for the Scout-type pop-up pistons. They went from 131 mph at Daytona that year to 150 the next spring and ate us ITriumnhs and BSAs1 alive.

"If the factory had not had a previously signed contract to use those sorry-ass Tillotson chainsaw carburetors, there was another 2 horsepower easily available with Mikunis, simply because the [mixture curve] was so much flatter over the whole range. Those Tillotsons were bloody maddening to even try and keep running through the whole rpm/vacuum range. Remember, they were pumpers, with no float bowl."

To the question "What kind of horse power did they make on the dyno?" Keen said, "About 53 at the time, but with the radical Axtell-prompted overhaul/redesign in four months of development, over 60."

Present-day overhead-cam engines, with very short strokes to enable them to reach high revs, have ended up with just as tough a compromise. To get acceleration, you need high compression. But high compression combined with short stroke and big bore makes the combustion chamber so wide and thin that flame propagation takes forever~ knocking power off of top end. To get top end, you open up the chamber to make room for turbulence that speeds flame propagation but then you lose acceleration from the lowered compression ratio.

Design is always compromise. Neil Keen and C.R. Axtell realized that the KR flathead's compromise was too far in the direction of high compression, which in its case, strangled the intake and exhaust flow. Dick O'Brien and Roy Bockelman used that idea to work out a better compromise, and the great Calvin Rayborn used it to win Daytona in 1968 and `69. The new fairing and dual carburetion contributed, as well.

The following year, the AMA gave all four-strokes the full 750cc, and everyone got busy tackling a fresh set of compromises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAmusement Parks And the Leisure Gap

May 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

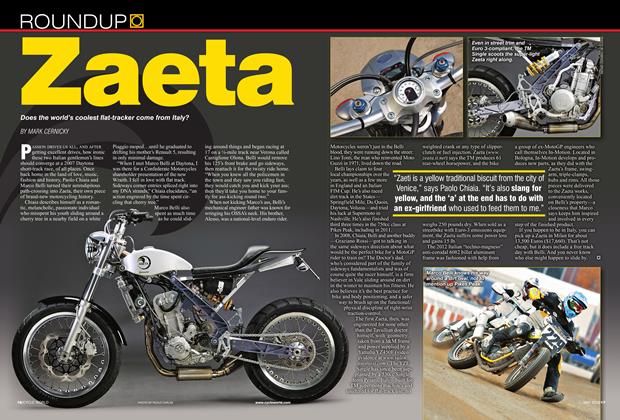

RoundupZaeta

May 2012 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

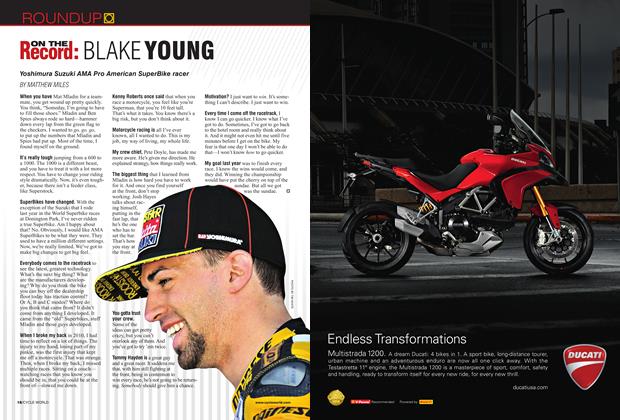

RoundupOn the Record: Blake Young

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRide Faster. Ride Safer.

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago May 1987

May 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupIs the Ducati For Everyone?

May 2012