GETTING THERE FIRST

RACE WATCH

Inside the NHRA Pro Stock Motorcycle class

KEVIN CAMERON

THIS PAST SPRING, A GASOLINE-BURNING NHRA PRO STOCK motorcycle achieved a 6.991-second, 196-mph quartermile run, taking the Mickey Thompson $10,000 prize for being the first to break 7 seconds in national competition. Vance & Hines' Andrew Hines, riding the Harley-Davidson V-Rod-inspired. 160-cubic-inch, pushrod two-valve Twin, achieved this in Gainesville, Florida, at the season-opening Mac Tools Gatornationals.

Motorcycle drag racing has become huge. NHRA now runs Pro Stock Motorcycle as the fourth class in its event order, indicating the increased popularity the class has achieved. This is no accident: It’s the result of careful rules structuring and that overused word “marketing." CIV decided to have a look, so off 1 went to Houston Raceway Park for Round Two.

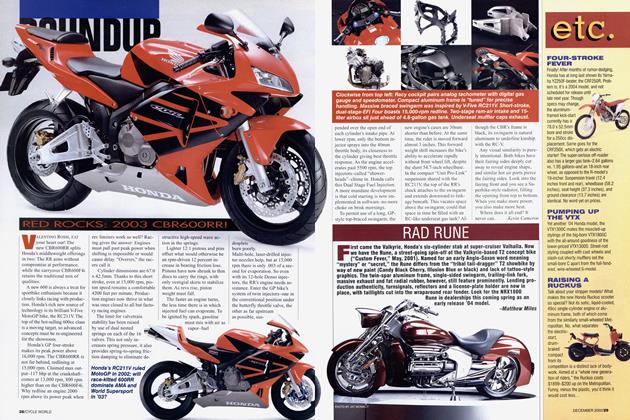

Pro Stock motorcycles are built-for-the-job dragbikes made to look vaguely like radically lowered late-model motorcycles with wheelie bars. They are powered by one of three basic engines: a two-valve Suzuki 1507cc inline-Four, a 262 lcc 60-degree pushrod V-Twin or a 3276cc 45-degree pushrod V-Twin-the latter are allowed up to 3276cc as their narrow Vee angle limits them to low-revving long strokes. Honda or Kawasaki four-valve Fours are welcome, too, but run at 1429cc. All are race-only engines without cooling systems, developed specifically for Pro Stock competition, and develop about 300 horsepower. In the interest of maximum acceleration, the engines are mounted low in special steel-tube chassis, as far forward as possible within a long 70-inch-maximum wheelbase. Propelling this is a slick tire limited to a 10-inch width. Onboard electronics report off-the-line rates of acceleration of 3 gs-about 2.5 times the maximum acceleration of a powerful streetbike. When these machines leave the line they get small very quickly.

My host at Houston was Steve Johnson, an 18-year veteran of this class who won the Gainesville meet, his second victory ever. He welcomed me into his pit and invited me to sit with him at the laptop as he both explained and pondered the wealth of computer data generated on each run. A Bryon Hines-built Suzuki, based on the early 1980s GS1100 bottom end, with an aftermarket cast two-valve head, powers his machine.

Almost more important to Johnson than winning personally is the growth of the Pro Stock class. He explained the controversies that have swirled around the oversized Twins are really irrelevant

to the central issue: People come to the races to be surprised, not bored by predictability. That requires rules agility to keep all equipment competitive. If this were not done, Pro Stock would collapse into a single-brand show and its new popularity would fade. Attracting Harley fans has been central to the growth of the class, and that is just what the special V&H “V-Rod” and S&S “Buell” big-

inch engines have done. When, after some dry seasons, the V&H team finally found the power to win races, NHRA gave the then-575-pound (total machine/rider weight) Twins a 40-pound weight increase. Hines set that 6.991 E.T. record this past March at the higher weight. The Suzukis have recently gained power from adoption of radius tappets, which allow increased valve lift within a given tappet diameter. NHRA, like any sanc tioning body, is a business, and its product is surprises-events whose winners are

not known beforehand. Keeping surprise in racing requires active management. Gone are the days when dmgsters smoked

off the line, but plenty of tire smoke is generated as rear slicks are pre-heated during burnout, starting in the waterbox. Startingline personnel then look like WWI soldiers staggering out of a gas attack. But the run itself is smokeless, with highly adjustable controlled-slip clutches holding the spin rate to an optimal 10-15 percent. Rules prevent electronics from actually controlling clutch operation, so the key to correct adjustment is the data generated during each run, downloaded to a laptop computer.

“School’s in session!” Johnson called out from the “office” of his giant tractortrailer rig. I climbed into the air-conditioned hush and he turned the laptop so we could both see the screen. Friday and Saturday’s runs are essentially practice, allowing teams to tune their setups to this 1320-foot piece of asphalt.

“Look at this,” he said. “This is the rear-wheel-speed curve. The speed jumps almost straight up from zero at the start. The tire has to spin at first, and then it’s supposed to arc over in a nice smooth curve that continues to rise for the rest of the run. But look here-it hooks over, peaks and then falls back onto the smooth curve. The tire is ‘over-speeding.’”

Then he called up other curves-four differently colored traces representing the exhaust-gas temperatures of the four cylinders. One of the four was below the other three. “These four should be like one line,” Johnson explained. “I’ve got one weak cylinder.” He jumped up and ran out of the truck, calling to his mechanic Shane Maloney for the borescope. The borescope is a flexible fiber-optic cable that can be inserted through a sparkplug hole to examine the piston crown burn pattern. Johnson peered in, moving the object around inside the cylinder. Gradually, I began to understand that all the information is taken in, but action based on what it means is postponed until just before the call to the starting lineup.

Atop the trailers of other teams I saw miniature weather stations. That of the Army team for which Angelle Sampey and Antron Brown ride has an anemometer. Johnson’s “weather bureau” is less imposing, but open on a table near it was a daily weather record with temperature, humidity and barometric pressure logged every hour. This shows the trend for the day, enabling operators to better predict what carburetion will be required during the next run.

While both the big Twins are fuelinjected, the Suzukis have carburetors, mostly Paul Gast-badged Lectron powerjets. Johnson’s final ritual before rolling out is an exchange of carburetion ideas with Shane.

“I say leave it alone!”

“Yeah, but I still think it’s weak...

Sitting ready is the jet block, awaiting the decision. Johnson screws in his choices

“Do you stagger the jetting? I asked.

“Yes, but Byron doesn’t approve,” Johnson replied.

Earlier, I heard another exchange, ending with a “fourpoint-eight!” from Johnson. That’s the tire pressure. With all 600 pounds transferring onto a 10inch slick, that pressure roughly translates to a 140 square-inch footprint-a lot of rubber on the ground.

Save for the huge noise of the car class just finishing, it’s pretty calm in the lineup. This is a tight community, full of camaraderie and shoptalk that includes the several women riders. Why the move to lightweight riders if the bike-and-rider total is set by rule? The lighter the rider, the more weight, in the form of lead plates, that can be located far forward, ahead of the crankcase. The greater the leverage it takes to lift the front wheel, the harder the launch can be.

The cars finish and the first pair of bikes advances. Start-carts-miniature versions of the “toilets” used by the car teams-are wheeled up. Inside are a battery, some tools and a starter that engages the end of the engine’s crankshaft. The engines are started, the Suzukis sounding like any big sportbike at high idle. The V&H Twin sounds a lot like a Harley, while the S&S monster makes a less regular bap-bap-bam sound. Water is sprayed down by a line crewman and the bikes back into the wet. Engines come up as the burnout begins, smoke taking a couple of seconds to appear. Some, like Johnson, bum out quite short. Others stay in it longer, raising a big cloud of blue. The riders oscillate the bars, generating a Dutch roll that heats the tires from edge to edge. As each bike rolls forward off the water, there is a jolt and a yelp as its tire bites dry pavement. Now, they approach the lights: pre-stage and stage. Each lights a yellow and the instant both bikes

have two yellows the start sequence begins. Engines flash instantly up to the first of their two-stage rev-limiters and stutter there. As the amber appears, both riders drop clutches and go. The win light and times appear on large overhead displays.

I spent some time with Byron Hines, asking him what it had taken to make his engine, which contains no more Harley parts than does the S&S, competitive.

“The Spintron,” was his reply. Spintron is not just one thing but a whole range of dynamic analysis services. Central to it is an electric motoring dynamometer and measuring systems that can map the actual movement of valve-train parts as the motor spins the engine at different rpm.

“We found that our valves weren’t moving anything like what the cam profile implied,” Hines revealed. “It’s worse on a Twin than on a V-Eight because the speed of a Twin’s crankshaft varies so much as the pistons stop and start and the engine fires. When we were done at Spintron, we had a different cam profile for each cylinder. But you’re not done yet. Once the valve motion is under control, you find that your power is down; the original cam profile was compensating for the bad motion. So now you have to develop

new profiles, and then settle down their motion. The Spintron people said, ‘Steel rocker arms.’ Stiffness is more important than weight. The NASCAR people have been around this block several times, and we’ll end up doing that, too. S&S came through Spintron about six months after us.”

Harley takes drag racing very seriously. Nearby was its giant motorhome with both racing and PR managers on hand. They had lots to say.

Farther up the row of tractor-trailers was Rob Muzzy, running his own chassis with one of the $40,000 S&S engines. Uniquely, his bike has carbon brakes, inherited from his roadrace past. Bore and stroke? Five-and-a-quarter by just under 3.7 inches. The ports are CNC-machined, hand-refined. Intake valves are almost 2.75 inches-twice the diameter and four times the area of intakes in a liter-bike. In this world, a liter is little and cute!

“Have you had any experience with Spintron?” I asked him.

“No, but I’m planning to in the near future,” he responded. “Or I may buy or build my own machine.”

One surprise in talking with Muzzy was social. “In all the years I was in roadracing, I never had a dealer come up to me with an order,” he said. “But at our first drag meet, a dealer handed me his card.

On the back was an order for 15 pipes. I’d always just assumed that roadracing was the way to reach people, but in the 18 months after we started drag racing, my business doubled. We weren’t ready for it!”

Earlier, I had watched cars stream into the spectator parking lot. It was a slice of America. A third of the vehicles were pickups, but there were many late-model cars, air conditioners on, filled with families. And I saw them-great crowds of people-in the pits. The stands were full at 9 a.m.

Muzzy tried hard to make a Kawasaki ZX-12R successful in drag racing before buying S&S engines. “You know me well enough to know that I don’t like failure,” he said. “In two years of trying, we qualified the ZX-12R twice.”

This reveals a truth about drag engines: Being uncooled, all their waste heat goes into their structure. Heat expansion distorts parts, especially a four-valve engine’s “exhaust bridge,” the bit of metal separating the two exhaust valves. If the valve seats move and go out of round, serious power will be lost. In drag racing, two-valve engines are king because they are easier to keep sealed as they get hot.

“If we ran the water jacket empty, we lost 10 hp,” Muzzy continued. “If we filled the head with cement (this is normal with many drag engines), we lost 3 hp.” All Pro Stock engines have crack-ofdoom instant throttle response because so much depends on what happens in the first 60 feet-the launch. A super 60-foot time is 1.08 seconds, which roughly translates to 3.2 gs. Sixty mph is reached in one second. The choice of engine rpm at the line (9000-10,000 revs for the Suzukis) determines how much energy is available for snatching the tire loose. If the revs are too high, tire slip is too fast to generate maximum grip. If too low, the tire may alternately slip-and-grip or “shake,” a condition so violent that it can chip or break riders’ teeth. After every run, the clutch-all use the Suzuki clutch because it’s well understood-is removed and its plates examined. These are flyweighted clutches, and the flyweights are on the pressure plate so their rpm is determined by rear-wheel speed.

Initial grip is set by six conventional clutch springs, their installed pressure adjusted after every run by shimming. Initial pressure and line rpm determine the way tire speed rises, but as it does so, the flyweights increase clutch pressure and reduce the clutch slip rate. When this is done exactly right, the wheel-speed curve has the desired steep initial rise that angles smoothly over into a steady up-slope.

Also on the computer screen are the points at which the rider’s shift light came on in each gear, and when the shifts were completed. Redline for the Suzukis is 14,000 rpm, the V&H Twin 9200 rpm. Because lower gears are closer together, rider reaction time is a larger part of the interval between shifts, so the shift lights have to be advanced to make everything happen on schedule, More decisions,

These are “automatic” six-speed transmissions that upshift by pneumatic actuator with zero power interruption. With one gear still driving, the next higher ratio is engaged without pulling the first pair out of engagement. The speed of the higher gear drives the previous gear backward, causing ramps ground on the back faces of its engaging dogs to kick that gear out of engagement. If the rider closes the throttle in any gear but sixth, transmission damage occurs.

Halfway through eliminations, Muzzy said, “At this point, any one of these people could win the event. Everything is that close.”

Spectators eat this up. Johnson made it to the semi-final round, refining his riding, his clutch and engine settings only to redlight. His E.T. was quick.

“When I start to get comfortable, I get faster,” he said. “I should have remembered that.” He showed me how riders slow their reaction time by raising the clutch lever angle, or by intentionally pumping up their arm muscles. All the complexity of other forms of racing is condensed into 7 seconds here.

After overcoming a bad clutch-speed sensor, Muzzy’s bike lost fire in its rear cylinder 10 feet out. Suzuki-mounted Karen Stoffer won the class, while Johnson’s work kept him in the points lead.

I didn’t want to leave this intense, information-packed scene. Even the darkening sky seemed engaged, but the longthreatened rain didn’t come until one minute after 5 p.m.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue