Lessons from The Glen

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

LAST WEEK, BARB AND I DECIDED TO squeeze one last weekend of fun into late autumn before winter turned on us like a rabid dog, so we towed my 1978 Formula Ford 800 miles, from Wisconsin out to Watkins Glen, New York, for a vintage race.

The Glen, which sits in the hills along Seneca Lake in the scenic Finger Lakes region, is a legendary track that Fd never driven before, though I’d once been there as a spectator.

That was back in 1979, when my buddy John Jaeger and I rode our motorcycles out there from Madison, Wisconsin, to see the U.S. Grand Prix for Formula 1 cars. It was the year a Ferrari, driven brilliantly by Gilles Villeneuve, won in the cold October rain.

And—wouldn’t you know it—when Barb and I drove through the gates last week, it was yet another rainy October afternoon. I pulled over and walked up to the fence along the track, looking out on the downhill sweep of Turn 1.

“This is exactly where John and I stood to watch qualifying 32 years ago,” I told Barb. “I think our bikes were parked right over there.”

“Did you camp at the track?” she asked. “Well, we had camping gear, but we were so cold and wet we got a cheap cabin somewhere near Watkins Glen. I can’t remember where,” I said. “I think my brain was frozen.”

A few memories, however, remained clear. John was riding his nearly new silver-smoke BMW R90S and I was on a metallic blue 1975 Honda CB750 Four. We’d been planning the trip all summer but, at the last minute, I concluded that my 1967 Triumph Bonneville was mechanically too tired to make a high-speed run all the way to New York in the company of an R90S, so I decided to sell the Triumph and buy a Honda 750.

I listed the Triumph in the classifieds, and the ad was answered by a wellknown local motorcycle collector named Kenny Bahl. He asked me why I was selling the Bonneville and I told him I needed a newer bike for a long road trip.

“I have a nice 1975 Honda CB750 I could trade you, straight across,” he said. Done deal.

The Honda four-piper was in excellent shape and had low mileage, but it had been sitting for a while in a damp barn, so all the electrical ground wires had turned green and needed cleaning. Also, the carbs were full of grit and the float needles and seats leaked. I took the carbs off and cleaned them—about three times—before everything worked right.

John and I left Madison on a dark Tuesday morning with temperatures hovering in the low 40s. By the time we got to Rockford, Illinois, we had to pull off at a restaurant called the Clock Tower and drink many cups of coffee, after running our hands under hot water in the men’s room. On the way out, we stuffed newspapers into the fronts of our jackets. John had a leather jacket and a sweater, and I had a Belstaff jacket and a wool sweater Barb had knitted.

It wasn’t enough.

After that, I don’t remember much about the trip except holding onto the handlebars with a death grip and shivering. Only a few pleasant moments stand out in my mind, like slightly out-offocus snapshots: a green, lovely stretch of farm road past huge yellow haystacks in southern Ontario; hot apple pie at a hilltop restaurant in the Alleghenies; an afternoon of perfect winding road through rural Pennsylvania, during which I kept thinking we should return sometime on a warm summer day. That’s about it.

So when Barb and I got home last week, I called John to see if his memory was any better than mine.

It was.

“We draped all our wet camping gear over the chairs and bed in that cabin in Watkins Glen while we went to the track,” he said, “and we were worried they’d throw us out for getting the furniture wet. Also, we almost crashed into a giant water-filled hole at a road construction site in Pennsylvania. We both did a lock-up slide on the muddy pavement and almost fell in.”

I could picture it: our faceshields fogged up, both of us tearing along a little too fast to properly interpret the yellow flashing barrier lights in the mist. Also, our hands and brains were frozen.

“Why were we so cold?” I asked John. “Why didn’t we plan better and take better riding gear along for the trip?”

“There wasn’t any,” he said flatly. “Or else we just didn’t know about it. No heated grips or seats. No insulated touring suits. No good rainproof touring boots. I don’t even think we had any real rain gear,” he added. “All we owned were hooded raincoats and baggy rain pants, and they flapped in the wind and leaked water down your chest and into your boots, so we didn’t bother to take them. Anyway, nobody really planned anything in those days; we just did it.” True enough. I had a supposedly rainproof waxed cotton Belstaff Trialmaster jacket, but the rain always soaked into the fabric eventually and you ended up as a giant Air Wick. The wind rushing over a rainsoaked Belstaff jacket could work quite nicely as a cooling tower for a nuclear reactor. I tried some cheap plastic rain pants, but they tore apart in the wind and, after much duct-taping, I threw them away.

My first bright yellow Dry Rider rain suit was still a year or two away. I might not have worn one anyway. We were way too cool to appear concerned about our comfort. As John says, we just did it, leaping into the unknown. These were the existential touring days.

“Okay, here’s another question,” I said. “Knowing it was probably going to be a wet, miserable week in October, why didn’t we just take a nice warm car out there, like your MGB?”

John thought about that for a few silent moments, then said, “Probably because a car trip would have been too easy. We’d wanted to go to a real Grand Prix at Watkins Glen since we were 13, and the trip deserved a certain amount of effort and sacrifice. A car wouldn’t have made it seem important enough.”

Of course. That was it. I’d almost forgotten. The pilgrimage factor.

Still, a momentous event deserves only so much respect, and I wouldn’t take this trip again without a windshield, heated grips, neck-warmer, waterproof boots, a decent rain suit and an electric vest. And a credit card for motels.

All of which I now possess, thanks to Watkins Glen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

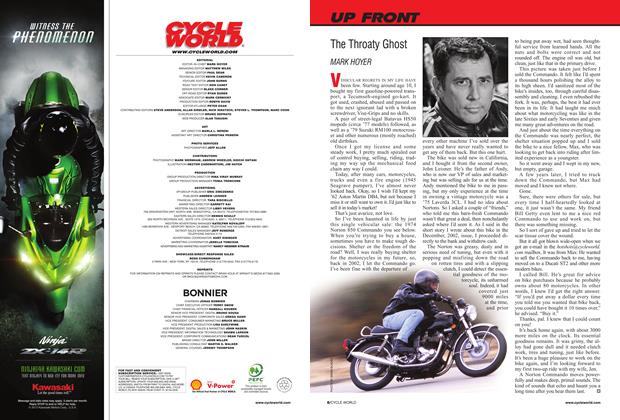

Up FrontThe Throaty Ghost

FEBRUARY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupWhat's the Two-Wheel World Coming To Anyway?

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

25 Years Ago February 1987

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Zeros

FEBRUARY 2012 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDaineses D-Air Street

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMilestones Along the Way

FEBRUARY 2012 By Paul Dean