BIGGER THAN LIFE

Remembering Gary Nixon

KEVIN CAMERON

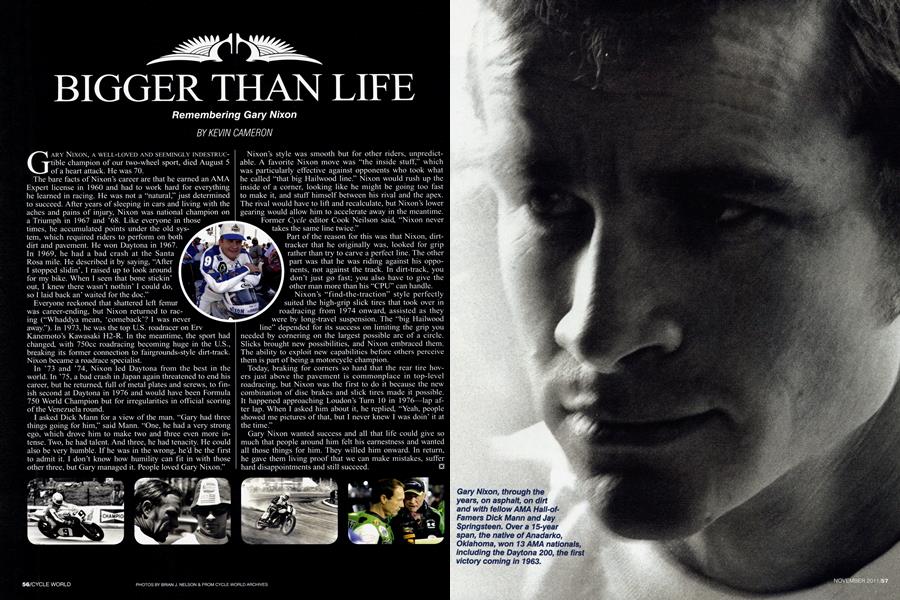

GARY NIXON, A WELL-LOVED AND SEEMINGLY INDESTRUCtible champion of our two-wheel sport, died August 5 of a heart attack. He was 70.

The bare facts of Nixon’s career are that he earned an AMA Expert license in 1960 and had to work hard for everything he learned in racing. He was not a “natural,” just determined to succeed. After years of sleeping in cars and living with the aches and pains of injury, Nixon was national champion on a Triumph in 1967 and ’68. Like everyone in those times, he accumulated points under the old system, which required riders to perform on both dirt and pavement. He won Daytona in 1967. In 1969, he had a bad crash at the Santa Rosa mile. He described it by saying, “After I stopped slidin’, I raised up to look around for my bike. When I seen that bone stickin’ out, I knew there wasn’t nothin’ I could do, so I laid back an’ waited for the doc.”

Everyone reckoned that shattered left femur was career-ending, but Nixon returned to racing (“Whaddya mean, ‘comeback’? I was never away.”). In 1973, he was the top U.S. roadracer on Erv Kanemoto’s Kawasaki H2-R. In the meantime, the sport had changed, with 750cc roadracing becoming huge in the U.S., breaking its former connection to fairgrounds-style dirt-track. Nixon became a roadrace specialist.

In ’73 and ’74, Nixon led Daytona from the best in the world. In ’75, a bad crash in Japan again threatened to end his career, but he returned, full of metal plates and screws, to finish second at Daytona in 1976 and would have been Formula 750 World Champion but for irregularities in official scoring of the Venezuela round.

I asked Dick Mann for a view of the man. “Gary had three things going for him,” said Mann. “One, he had a very strong ego, which drove him to make two and three even more intense. Two, he had talent. And three, he had tenacity. He could also be very humble. If he was in the wrong, he’d be the first to admit it. I don’t know how humility can fit in with those other three, but Gary managed it. People loved Gary Nixon.”

Nixon’s style was smooth but for other riders, unpredictable. A favorite Nixon move was “the inside stuff,” which was particularly effective against opponents who took what he called “that big Hailwood line.” Nixon would rush up the inside of a corner, looking like he might be going too fast to make it, and stuff himself between his rival and the apex. The rival would have to lift and recalculate, but Nixon’s lower gearing would allow him to accelerate away in the meantime. Former Cycle editor Cook Neilson said, “Nixon never takes the same line twice.”

Part of the reason for this was that Nixon, dirttracker that he originally was, looked for grip rather than try to carve a perfect line. The other part was that he was riding against his opponents, not against the track. In dirt-track, you don’t just go fast; you also have to give the other man more than his “CPU” can handle. Nixon’s “find-the-traction” style perfectly suited the high-grip slick tires that took over in roadracing from 1974 onward, assisted as they were by long-travel suspension. The “big Hailwood line” depended for its success on limiting the grip you needed by cornering on the largest possible arc of a circle. Slicks brought new possibilities, and Nixon embraced them. The ability to exploit new capabilities before others perceive them is part of being a motorcycle champion.

Today, braking for corners so hard that the rear tire hov ers just above the pavement is commonplace in top-level roadracing, but Nixon was the first to do it because the new combination of disc brakes and slick tires made it possible. It happened approaching Loudon's Turn 10 in 1976-lap af ter lap. When I asked him about it, he replied.. "Yeah, people showed me pictures of that, but I never knew I was do in' it at the time."

Gary Nixon wanted success and all that life could give so much that people around him felt his earnestness and wanted all those things for him. They willed him onward. In return, he gave them living proof that we can make mistakes, suffer hard disappointments and still succeed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

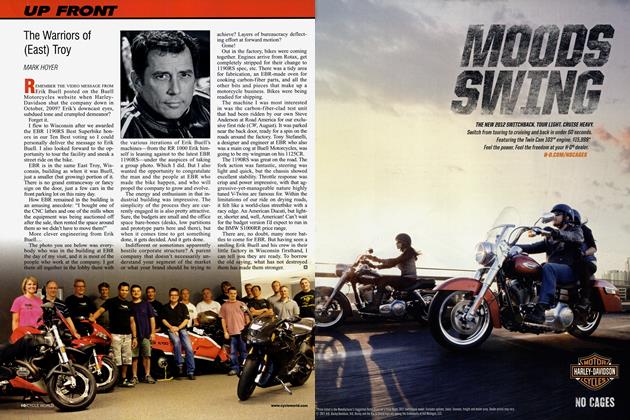

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

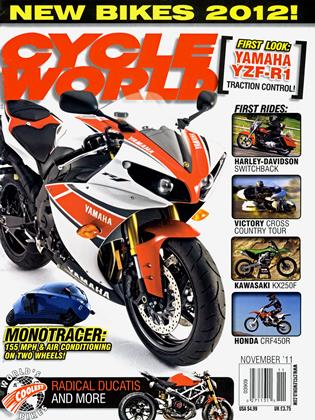

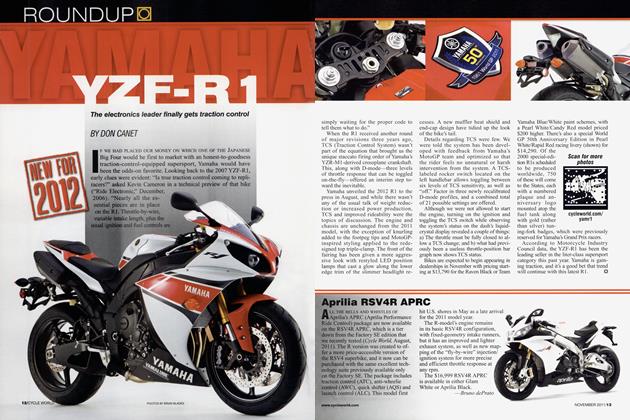

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet