LEANINGS

Upturns and downturns

Peter Egan

ON MY CAR RADIO THE OTHER NIGHT, there was a psychologist giving advice on how married couples should handle the stress of the current economic downturn.

He said (and I paraphrase here, not having had a tape recorder on me):

“I would advise you to think back on what life was like when you were young and first married—the apartments, the budget meals, the cheap jug wine, the old cars—and ask yourself if it was really so bad. Was it the worst time in your life? Probably not. It may even have been the best. Sometimes it’s not so bad to take yourself back there to a time of less stress and simpler pleasures.”

Hmmm....

Easy to say, I thought to myself, if you don’t have three kids in school and a mortgage-as so many in our own hard-hit county now do. Like telling people on the Titanic to savor their excellent new swimming opportunities.

Simplicity is a luxury not everyone can afford. Still, the man’s point was worth pondering. Especially for some of us-like Barb and me-who are presently downsizing and scaling back a bit, as she’s retiring this summer.

I shut off the radio and tried to reflect on the pros and cons of our own more frugal past. Would we want to go back there?

After I got out of the Army in the early Seventies, I finished college and graduated with a shiny new Journalism degree in December of 1972. Minutes after I got my diploma, someone phoned Wall Street and told them to flip on the Recession Switch.

There were no jobs. And I mean none.

The economy was in the dumpster and newspapers were folding all over the place. Every time I applied for a writing job, the editor would roll open a file drawer and say, “Here are some job applications from people who used to work for the Chicago Sun Times. Should we hire them or you?”

Suitably browbeaten, I looked for other work. I had applications rejected for driving a garbage truck; driving a laundry truck; selling cameras at a camera shop; stenciling road signs for the highway department. Finally our landlord, a good guy named Jim Corcoran, hired me to install rain gutters for his sheetmetal company.

I did that for about two years but finally quit one day after my extension ladder blew over in the wind-with me on it. I saved myself by whipping out my claw hammer and digging it into the sill of a third-story window, like a mountain climber with an ice axe.

Finding myself miraculously still alive, I took a job as an apprentice foreign car mechanic (starting wage, $2 per hour) and did that for seven years.

I enjoyed this career a lot, but during those early years of the Seventies I wasn’t exactly buying yachts and caviar. Or 750SS Ducatis. Luckily, Barb had a job as a physical therapist at a nearby hospital and we got by.

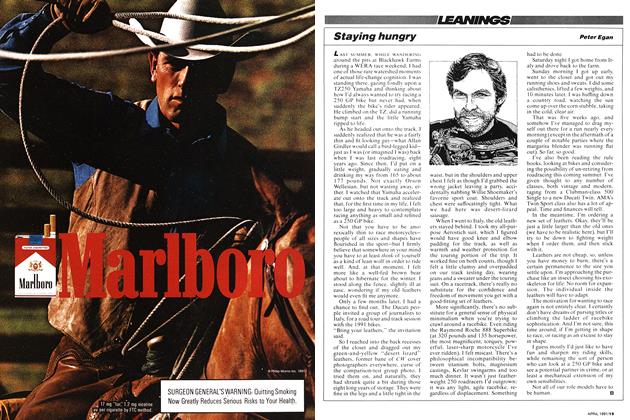

We rented the upstairs of a nice old house in a shady, tree-lined neighborhood, where we had big spaghetti dinners and threw parties at which people drank gallons of Hearty Burgundy and Boone’s Farm Apple Wine and listened to the Allman Brothers loud on the stereo. For further cheap entertainment, we went to $1 movies on campus, regularly turning our sofa upside down for loose change to get the money. For transportation, we owned a slightly rusty 1968 Volkswagen Beetle.

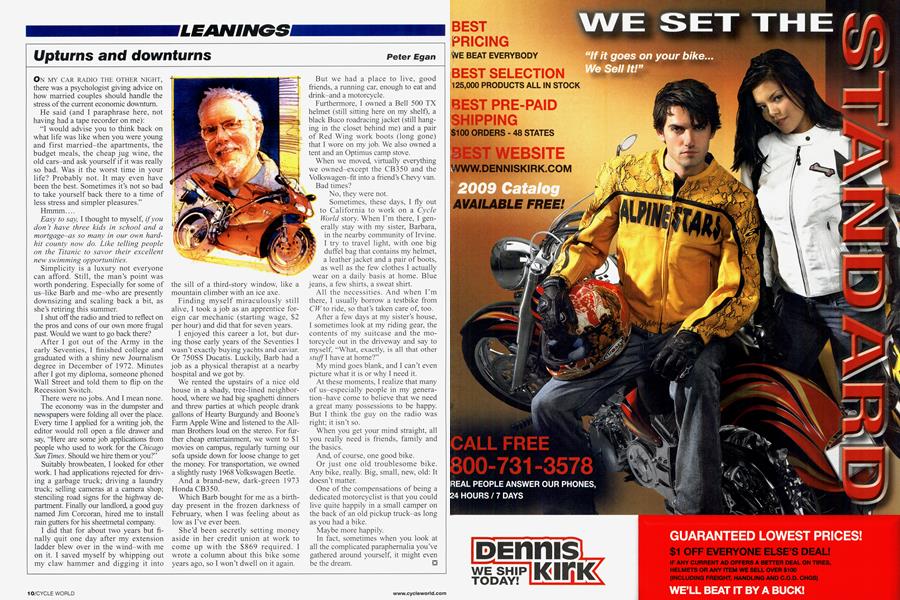

And a brand-new, dark-green 1973 Honda CB350.

Which Barb bought for me as a birthday present in the frozen darkness of February, when I was feeling about as low as I’ve ever been.

She’d been secretly setting money aside in her credit union at work to come up with the $869 required. I wrote a column about this bike some years ago, so I won’t dwell on it again.

But we had a place to live, good friends, a running car, enough to eat and drink-and a motorcycle.

Furthermore, I owned a Bell 500 TX helmet (still sitting here on my shelf), a black Buco roadracing jacket (still hanging in the closet behind me) and a pair of Red Wing work boots (long gone) that I wore on my job. We also owned a tent and an Optimus camp stove.

When we moved, virtually everything we owned-except the CB350 and the Volkswagen-fit into a friend’s Chevy van.

Bad times?

No, they were not.

Sometimes, these days, I fly out to California to work on a Cycle World story. When I’m there, I generally stay with my sister, Barbara, in the nearby community of Irvine. I try to travel light, with one big duffel bag that contains my helmet, a leather jacket and a pair of boots, as well as the few clothes I actually wear on a daily basis at home. Blue jeans, a few shirts, a sweat shirt.

All the necessities. And when I’m there, I usually borrow a testbike from CWto ride, so that’s taken care of, too.

After a few days at my sister’s house, I sometimes look at my riding gear, the contents of my suitcase and the motorcycle out in the driveway and say to myself, “What, exactly, is all that other stuff I have at home?”

My mind goes blank, and I can’t even picture what it is or why I need it.

At these moments, I realize that many of us-especially people in my generation-have come to believe that we need a great many possessions to be happy. But I think the guy on the radio was right; it isn’t so.

When you get your mind straight, all you really need is friends, family and the basics.

And, of course, one good bike.

Or just one old troublesome bike. Any bike, really. Big, small, new, old: It doesn’t matter.

One of the compensations of being a dedicated motorcyclist is that you could live quite happily in a small camper on the back of an old pickup truck-as long as you had a bike.

Maybe more happily.

In fact, sometimes when you look at all the complicated paraphernalia you’ve gathered around yourself, it might even be the dream.