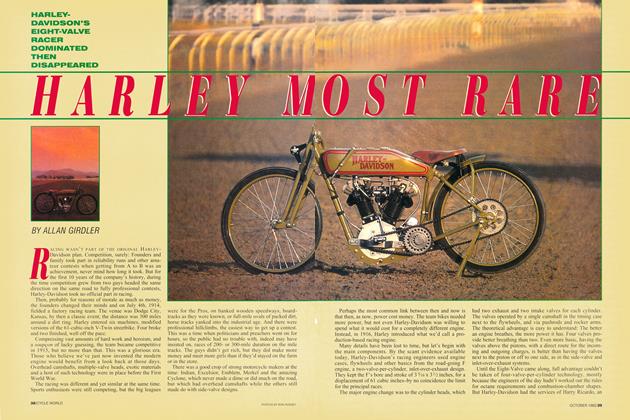

THE MILE

When flat-track was fab

PETER JONES

It’s fascinating how we’re unwittingly shaped not just by when we live but by where we live. Shaped by our “sense of place.” Growing up in Syracuse, New York, made me think Italian bread was on every dinner table. Seeing the sun was a rare and frightening experience. Hot dogs were red or white.

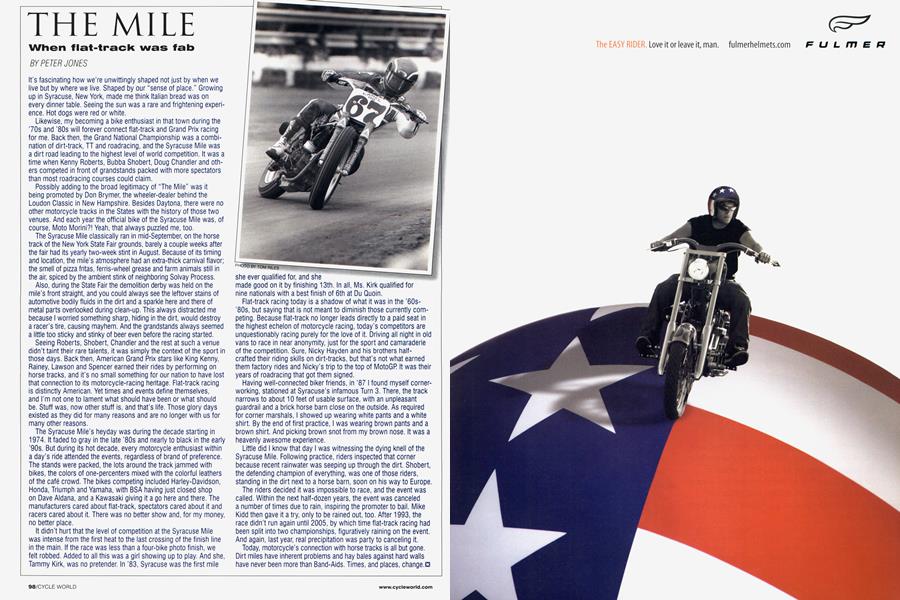

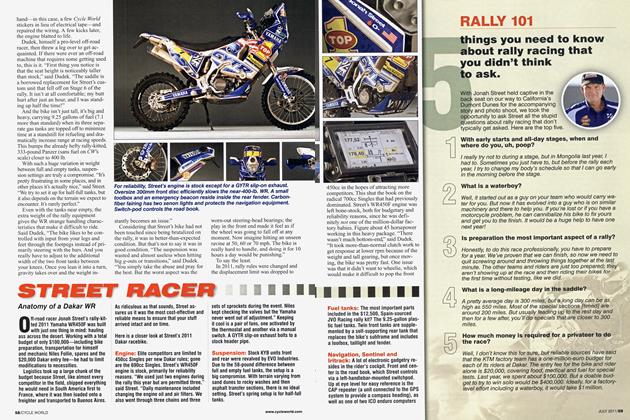

Likewise, my becoming a bike enthusiast in that town during the 70s and '80s will forever connect flat-track and Grand Prix racing for me. Back then, the Grand National Championship was a combination of dirt-track, TT and roadracing, and the Syracuse Mile was a dirt road leading to the highest level of world competition. It was a time when Kenny Roberts, Bubba Shobert, Doug Chandler and others competed in front of grandstands packed with more spectators than most roadracing courses could claim.

Possibly adding to the broad legitimacy of “The Mile” was it being promoted by Don Brymer, the wheeler-dealer behind the Loudon Classic in New Hampshire. Besides Daytona, there were no other motorcycle tracks in the States with the history of those two venues. And each year the official bike of the Syracuse Mile was, of course, Moto Morini?! Yeah, that always puzzled me, too.

The Syracuse Mile classically ran in mid-September, on the horse track of the New York State Fair grounds, barely a couple weeks after the fair had its yearly two-week stint in August. Because of its timing and location, the mile’s atmosphere had an extra-thick carnival flavor; the smell of pizza fritas, ferris-wheel grease and farm animals still in the air, spiced by the ambient stink of neighboring Solvay Process.

Also, during the State Fair the demolition derby was held on the mile’s front straight, and you could always see the leftover stains of automotive bodily fluids in the dirt and a sparkle here and there of metal parts overlooked during clean-up. This always distracted me because I worried something sharp, hiding in the dirt, would destroy a racer’s tire, causing mayhem. And the grandstands always seemed a little too sticky and stinky of beer even before the racing started.

Seeing Roberts, Shobert, Chandler and the rest at such a venue didn’t taint their rare talents, it was simply the context of the sport in those days. Back then, American Grand Prix stars like King Kenny, Rainey, Lawson and Spencer earned their rides by performing on horse tracks, and it’s no small something for our nation to have lost that connection to its motorcycle-racing heritage. Flat-track racing is distinctly American. Yet times and events define themselves, and I’m not one to lament what should have been or what should be. Stuff was, now other stuff is, and that’s life. Those glory days existed as they did for many reasons and are no longer with us for many other reasons.

The Syracuse Mile’s heyday was during the decade starting in 1974. It faded to gray in the late '80s and nearly to black in the early ’90s. But during its hot decade, every motorcycle enthusiast within a day’s ride attended the events, regardless of brand of preference. The stands were packed, the lots around the track jammed with bikes, the colors of one-percenters mixed with the colorful leathers of the café crowd. The bikes competing included Harley-Davidson, Honda, Triumph and Yamaha, with BSA having just closed shop on Dave Aldana, and a Kawasaki giving it a go here and there. The manufacturers cared about flat-track, spectators cared about it and racers cared about it. There was no better show and, for my money, no better place.

It didn’t hurt that the level of competition at the Syracuse Mile was intense from the first heat to the last crossing of the finish line in the main. If the race was less than a four-bike photo finish, we felt robbed. Added to all this was a girl showing up to play. And she, Tammy Kirk, was no pretender. In ’83, Syracuse was the first mile

she ever qualified for, and she

made good on it by finishing 13th. In all, Ms. Kirk qualified for nine nationals with a best finish of 6th at Du Quoin.

Flat-track racing today is a shadow of what it was in the ’60s’80s, but saying that is not meant to diminish those currently competing. Because flat-track no longer leads directly to a paid seat in the highest echelon of motorcycle racing, today’s competitors are unquestionably racing purely for the love of it. Driving all night in old vans to race in near anonymity, just for the sport and camaraderie of the competition. Sure, Nicky Hayden and his brothers halfcrafted their riding skills on dirt-tracks, but that’s not what earned them factory rides and Nicky’s trip to the top of MotoGP It was their years of roadracing that got them signed.

Having well-connected biker friends, in ’87 I found myself cornerworking, stationed at Syracuse’s infamous Turn 3. There, the track narrows to about 10 feet of usable surface, with an unpleasant guardrail and a brick horse barn close on the outside. As required for corner marshals, I showed up wearing white pants and a white shirt. By the end of first practice, I was wearing brown pants and a brown shirt. And picking brown snot from my brown nose. It was a heavenly awesome experience.

Little did I know that day I was witnessing the dying knell of the Syracuse Mile. Following practice, riders inspected that corner because recent rainwater was seeping up through the dirt. Shobert, the defending champion of everything, was one of those riders, standing in the dirt next to a horse barn, soon on his way to Europe.

The riders decided it was impossible to race, and the event was called. Within the next half-dozen years, the event was canceled a number of times due to rain, inspiring the promoter to bail. Mike Kidd then gave it a try, only to be rained out, too. After 1993, the race didn’t run again until 2005, by which time flat-track racing had been split into two championships, figuratively raining on the event. And again, last year, real precipitation was party to canceling it.

Today, motorcycle’s connection with horse tracks is all but gone. Dirt miles have inherent problems and hay bales against hard walls have never been more than Band-Aids. Times, and places, change.o