The mechanization of slip-grip thrills

TDC

Kevin Cameron

As THE 1980S CAME TO AN END, THE DIFficulty of riding 500cc two-stroke GP bikes peaked. I watched this often from Laguna Seca’s Turn 11, the final first-gear left before start-finish. As riders began to throttle-up, engines would give two sharp pops, then kick the back end out as power cut in. The corner exit would be a jerky affair as the rear tire alternately kicked sideways, gripped and kicked again.

Riders prepared for this by pulling themselves far forward on the bikes, then giving clearance for the gyrations by moving knees and elbows out. As numerous riders high-sided in this way, and quite a few were injured, many theories of what was at fault were put forward. The FIM announced a program of higher minimum weights with a threat of horsepower control via intake restrictions. At the time, corner-exit high-sides were seen as a crisis in the sport.

Today not only is this not looked back upon as a time of serious threat to riders but is actually being hailed as a golden age. We are told that riders were truly in control of their machines, thrilling spectators by their visible efforts to avoid being flung over the top. Why are people saying such things? It is because traction control systems are now in use on MotoGP and some other roadracing machines, which allow all riders to get strong, secure drives off of corners. This, some are complaining, has made racing less exciting.

In fact, what we were watching in the previous era, and what was so thrilling to some spectators, was riders not in control of their machines, trying to race in spite of the uncontrollability of their bikes.

All that has since changed. As morning practice began some years ago at Laguna, I noticed that the evil 500s had changed their nature. Instead of the violence of slip-and-grip corner exits, I was seeing strong, smooth drives most of the time. Something was different. Soon I learned that torque controls had been developed. Some were as simple as using a shift-drum switch to change the ignition curve in each of the first three gears. In this way, the hard edge could be taken off engine torque in just the gears in which the danger of wheelspin and rear grip loss was greatest. More advanced systems, aimed at actively detecting excessive rear wheel acceleration and stopping it, were said to be under development. Bear in mind that this was taking place more than 15 years ago.

Before the automatic carburetor came into use after 1903, all motorcyclists had to simultaneously adjust fuel and air flows-separately. Until the early 1920s, total-loss oiling systems required all motorcyclists to operate a hand oil pump periodically to keep their engines lubricated. As recently as the 1960s, racing motorcycles confronted riders with both ignition timing and mixture control levers mounted on the handlebar. GP riders had to divide their attention between machine control and engine management as they raced bikes whose valves would bounce only 300 revs above peak power. Manual cold-start enrichment devices-“chokes”-continue to be seen on carbureted models. There has since the earliest days been a steady-and quite proper-mechanization of routine functions once controlled by the rider. This process has not stopped now, nor will it stop.

When the first carbon-carbon brake discs proved to offer tricky, steeply-rising initial brake torque that threw riders on the ground, technologies were developed that solved the problem. There was no one uttering nonsense like, “A real rider wouldn’t accept help in controlling brake torque. He’d just get on with it, and the fans would revel in his exciting battle with the forces of nature.”

Today in MotoGP and Superbike, lack of smoothness in engine torque delivery can cause the mirror image of the variable brake-torque problem-unintended wheelspin and loss of traction during corner exit. A variety of traction-control technologies now exists to overcome this. Yet suddenly, much nonsense like the above is being uttered, and there is talk of banning these technologies.

This is especially silly since Yamaha in Europe now offers an electronic traction-control box for the fly-by-wire throttle on the new R6. One thousand Euros and it’s yours. Other systems are under development in the aftermarket for half to two-thirds that price. Despite my initial skepticism, it will soon be in dealer showrooms. In two years there will be no more discussion-everyone will have it and everyone will therefore be equal. Meanwhile, controversy rages. It costs too much! Only the top teams can have it! It kills spectator interest! (Are these spectators enthusiasts or ghouls, I wonder?) Real riders should be in total control! (Does that mean banning gear-driven oil pumps and computercontrolled ignition and fuel-injection?)

A big meeting was held in Rome on June 6 to discuss this. It has been suggested that backers of MotoGP, soon to drop its displacement to 800cc for completely unknown reasons, fear that 1 OOOcc Superbikes with traction control will nibble or even munch heartily on the vaunted superiority of MotoGP lap times. Others caution that it’s silly to ban anything that will soon be on every streetbike. Still others ask if spectators want racing, or if it’s the prospect of demolition derby that brings them to the track. Racers race-they don’t operate oil pumps, fiddle with sparkadvance and mixture-control levers, or nobly take their chances with brake systems that lock without warning. Why then should they be at the mercy of the similarly tricky relationship between rubber polymers and engine torque spikes?

I see the change in racing. Almost no one high-sides any more. Corner exits are smooth and powerful, with the occasional traction loss taking the form of a sloweddown weave oscillation that puts the machine back in line. But a close duel is still extremely exciting, as I saw in the engagement between Suzuki riders Mat Mladin and young challenger Ben Spies at Road America this past weekend. Making those men fiddle with unnecessarily tricky controls or double as oil pumps could not have made the racing better.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

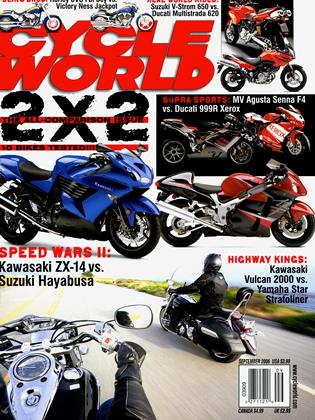

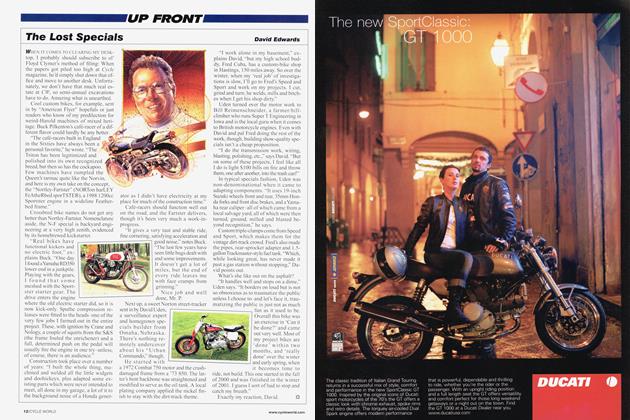

Up FrontThe Lost Specials

September 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDangerous Liaisons

September 2006 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2006 -

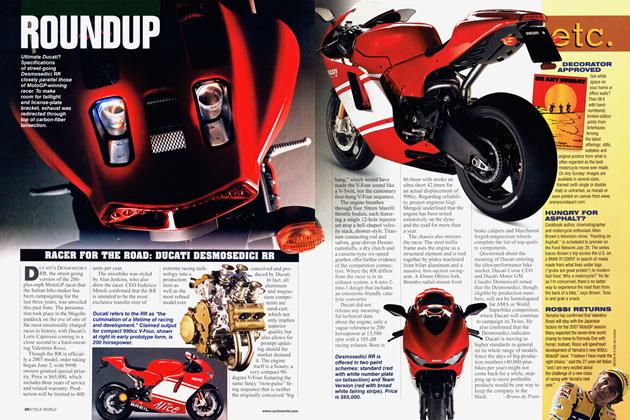

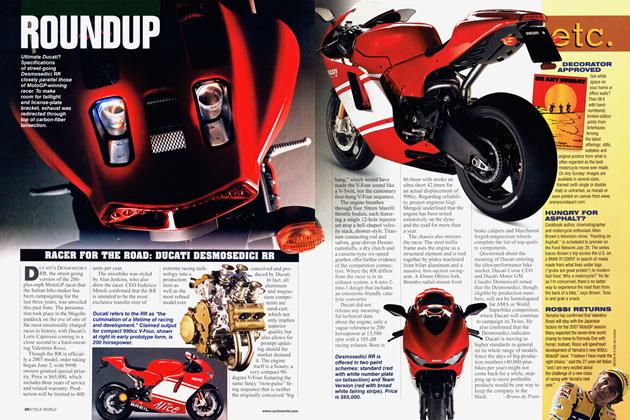

Roundup

RoundupRacer For the Road: Ducati Desmosedici Rr

September 2006 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

September 2006 -

Roundup

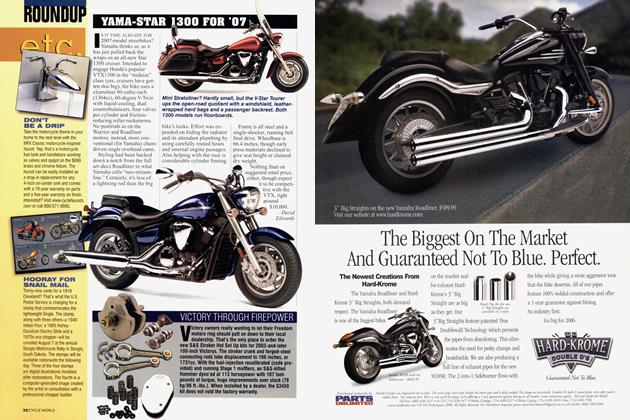

RoundupYama-Star 1300 For '07

September 2006 By David Edwards