This is the Golden Age

TDC

Kevin Cameron

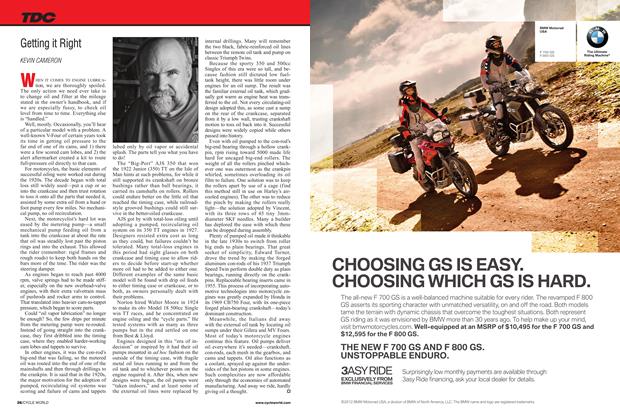

SUPERSPORT ROADRACING, AS PRACTICED in the U.S., begins with a stock 600cc four-cylinder sportbike. It allows almost no engine modifications other than improved valve seating. Suspension springs and rear damper may be changed, and road-only parts like lights and mirrors must be removed. Tires must be DOT listed. That’s pretty much it.

Who would have thought such a simple set of rules would do so much for sportbike design? What has happened is that manufacturers, vying with one another to win this crucial class, have since 1987 successively upgraded their machines in every detail until they have become positively the most high-performance motorcycle for the dollar that has ever existed.

Where else can you find 16,000-rpm powerplants, fed by FI-like multi-injector induction systems, delivering power through back-torque-limiting clutches? Where else can you find such excellent chassis qualities, combined with wide adjustability? Where else brakes big enough for a car, that can take the heating of maximum-^ stopping again and again without losing their performance? Similar qualities exist in 750 and lOOOcc sportbikes and have diffused outward into all road bikes, elevating their capabilities as well.

To see how far the production motorcycle has come, go back to the early days of the AMA Superbike class, 1976-78. The 150 horsepower that wowed us then from a no-holds-barred 1025cc engine would proportion to only a soggy 90 hp from 600cc today-only about 65 percent of what a good present-day Supersport engine makes. And those leaping tube-framed garden tillers of yore wouldn’t run in a straight line unless their chassis were braced, gusseted and sheeted-in to give them some minimal degree of added stiffness. I saw them at Riverside, California, in 1977-a procession of out-of-balance machines too fast for their chassis and suspension, all weaving and shaking in unison.

Even making no more power than today’s 600s, those wheezy dinosaurs blew up regularly. Oil sloshed away from pump pickups and bearings spun. Con-rod bolts snapped. Cranks cracked apart from torsional vibes. Valves and pistons tasted forbidden kisses. We became accustomed to the brittle crunch-sounding like someone had stepped on a really big beetlethat engines made as they blew. Superbike teams in those faraway days used to

stack the burst-open, stripped crankcases blown in practice outside their garages as negative trophies.

The industry responded, upgrading components and concepts. Braced swingarms became stock. Stock bikes appeared with GP-style twin-beam aluminum chassis. Sputter-and-stall carburetion was replaced by fuel-injection, whose initial defects were replaced by near-perfection. Stock cranks, rods and valve springs began to be made of high-specification but affordable materials that did not fail. Street engines began to routinely achieve levels of breathing and power production that would do credit to a pure race engine. And they combined this with smooth, usable torque-not the torque curves of spikes and chasms that formerly graced production-based racers.

I remember Superbike teams waiting in the tech lines in the late 1970s. Someone would come running back from the front of the line, whispering, “They just let a set of smoothbores through!” And every team in line would start stripping off their bored-out no-performance stock carbs to replace them with the race-only smoothbores everyone carried along, just in case. It was hard to get both airflow and throttle response from carburetorsbig holes meant low air velocity and poor vaporization. Fuel-injection has broken that compromise. Carburetor

throttle slides were strongly sucked shut by engine vacuum, making mid-corner throttle-up very tricky. Twist harder and harder on the throttle grip, then suddenly POP!, the slides come up, power whams in, and the bike is sideways. Modem butterfly throttles are balanced, easy to turn. Throttle-up is smooth, confidenceinspiring.

What does all this tell us? In the old days it was said that “racing improves the breed.” That meant that what manufacturers learned in pure racing classes might in time be applied to the design and manufacture of production vehicles. Race on Sunday, sell on Monday (or whenever we get around to exploiting the expensive lessons we’ve learned in racing).

But what has happened in Supersport is different, because it’s i not a pure racing class. What you see is what you race. If a pure race engine has a problem, the easy fix is some kind of unobtanium upgrade, like a double-vacuum-remelted crank, rod or valve-spring alloy. Build a hundred parts sets and you’re done. But when your problem is in Supersport, you have to upgrade all the bikes you build, quickly, before one of them embarrasses you by trailing oil and smoke in front of thousands of spectators and staring TV cameras. And you have to be very clever about it or the improvements will eat up all your profit. That means finding costeffective technologies that every buyer can afford.

All this is subject to the criticism that asks, “Why do we need ceaseless increases in performance? Human capabilities don’t increase over time, so why should vehicle performance do so?” Well, Norton built its pushrod Single Model 18 for decades, changing it very little. It was a bit of a breakthrough in the 1920s, but pretty no-fun by 1953. We can say that through fog and occasional sunshine it thumped a generation of Englishmen to where they needed to go. It sold on the basis of proven if unexciting value in an era of utility transportation.

Frankly, I don’t want to discuss whether or not human life as we presently live it makes sense or not, and I don’t care to debate fun versus utility. I like what’s happened to production sportbikes-this is the golden age. We can talk about global warming and the moral nuances of marketing some other time.