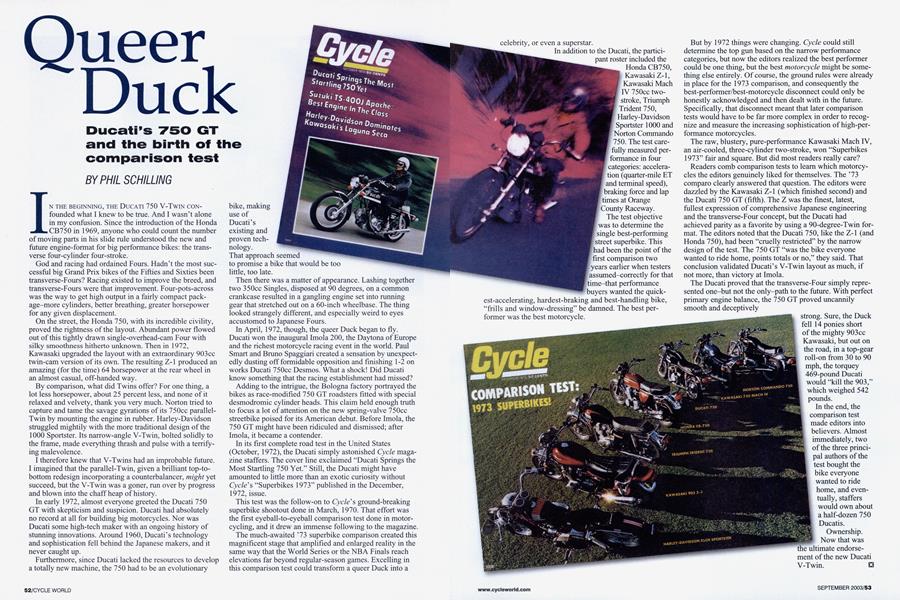

Queer Duck

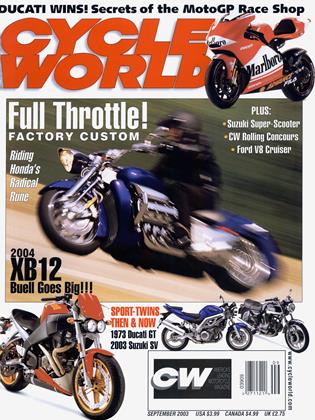

Ducati's 750 GT and the birth of the comparison test

PHIL SCHILLING

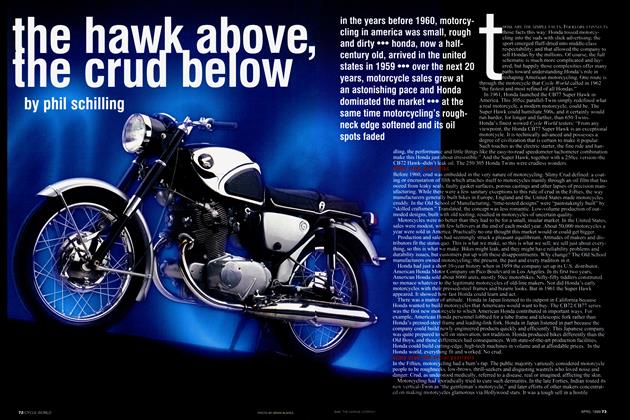

IN THE BEGINNING, THE DUCATI 750 V-TWIN CON-founded what I knew to be true. And I wasn't alone in my confusion. Since the introduction of the Honda CB750 in 1969, anyone who could count the number of moving parts in his slide rule understood the new and future engine-format for big performance bikes: the transverse four-cylinder four-stroke.

God and racing had ordained Fours. Hadn’t the most successful big Grand Prix bikes of the Fifties and Sixties been transverse-Fours? Racing existed to improve the breed, and transverse-Fours were that improvement. Four-pots-across was the way to get high output in a fairly compact package-more cylinders, better breathing, greater horsepower for any given displacement.

On the street, the Honda 750, with its incredible civility, proved the rightness of the layout. Abundant power flowed out of this tightly drawn single-overhead-cam Four with silky smoothness hitherto unknown. Then in 1972, Kawasaki upgraded the layout with an extraordinary 903cc twin-cam version of its own. The resulting Z-1 produced an amazing (for the time) 64 horsepower at the rear wheel in an almost casual, off-handed way.

By comparison, what did Twins offer? For one thing, a lot less horsepower, about 25 percent less, and none of it relaxed and velvety, thank you very much. Norton tried to capture and tame the savage gyrations of its 750cc parallelTwin by mounting the engine in rubber. Harley-Davidson struggled mightily with the more traditional design of the 1000 Sportster. Its narrow-angle V-Twin, bolted solidly to the frame, made everything thrash and pulse with a terrifying malevolence.

I therefore knew that V-Twins had an improbable future.

I imagined that the parallel-Twin, given a brilliant top-tobottom redesign incorporating a counterbalancer, might yet succeed, but the V-Twin was a goner, run over by progress and blown into the chaff heap of history.

In early 1972, almost everyone greeted the Ducati 750 GT with skepticism and suspicion. Ducati had absolutely no record at all for building big motorcycles. Nor was Ducati some high-tech maker with an ongoing history of stunning innovations. Around 1960, Ducati’s technology and sophistication fell behind the Japanese makers, and it never caught up.

Furthermore, since Ducati lacked the resources to develop a totally new machine, the 750 had to be an evolutionary bike, making use of Ducati’s existing and proven technology.

That approach seemed to promise a bike that would be too little, too late.

Then there was a matter of appearance. Lashing together two 350cc Singles, disposed at 90 degrees, on a common crankcase resulted in a gangling engine set into running gear that stretched out on a 60-inch wheelbase. The thing looked strangely different, and especially weird to eyes accustomed to Japanese Fours.

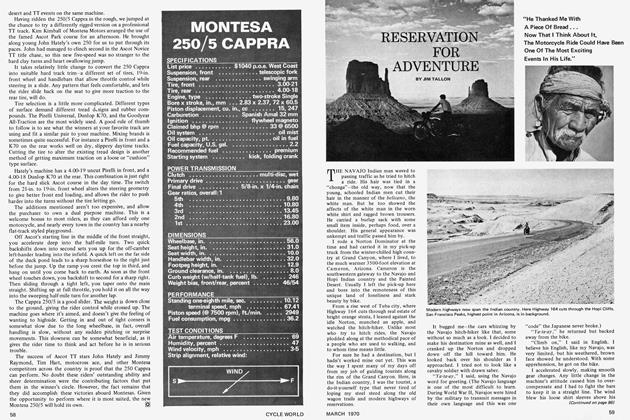

In April, 1972, though, the queer Duck began to fly. Ducati won the inaugural Imola 200, the Daytona of Europe and the richest motorcycle racing event in the world. Paul Smart and Bruno Spaggiari created a sensation by unexpectedly dusting off formidable opposition and finishing 1-2 on works Ducati 750cc Desmos. What a shock! Did Ducati know something that the racing establishment had missed?

Adding to the intrigue, the Bologna factory portrayed the bikes as race-modified 750 GT roadsters fitted with special desmodromic cylinder heads. This claim held enough truth to focus a lot of attention on the new spring-valve 750cc streetbike poised for its American debut. Before Imola, the 750 GT might have been ridiculed and dismissed; after Imola, it became a contender.

In its first complete road test in the United States (October, 1972), the Ducati simply astonished Cycle magazine staffers. The cover line exclaimed “Ducati Springs the Most Startling 750 Yet.” Still, the Ducati might have amounted to little more than an exotic curiosity without Cycle's “Superbikes 1973” published in the December, 1972, issue.

This test was the follow-on to Cycle's ground-breaking superbike shootout done in March, 1970. That effort was the first eyeball-to-eyeball comparison test done in motorcycling, and it drew an immense following to the magazine.

The much-awaited ’73 superbike comparison created this magnificent stage that amplified and enlarged reality in the same way that the World Series or the NBA Finals reach elevations far beyond regular-season games. Excelling in this comparison test could transform a queer Duck into a celebrity, or even a superstar. In addition to the Ducati, the participant roster included the

Honda CB750, Kawasaki Z-l, Kawasaki Mach IV 750cc twostroke, Triumph Trident 750, Harley-Davidson Sportster 1000 and Norton Commando 50. The test caretully measured performance in four categories: acceleration (quarter-mile ET and terminal speed), braking force and lap times at Orange County Raceway.

The test objective was to determine the single best-performing street superbike. This had been the point of the first comparison two years earlier when testers I assumed-correctly for that time-that performance buyers wanted the quickest-accelerating, hardest-braking and best-handling bike, “frills and window-dressing” be damned. The best performer was the best motorcycle.

But by 1972 things were changing. Cycle could still determine the top gun based on the narrow performance categories, but now the editors realized the best performer could be one thing, but the best motorcycle might be something else entirely. Of course, the ground rules were already in place for the 1973 comparison, and consequently the best-performer/best-motorcycle disconnect could only be honestly acknowledged and then dealt with in the future. Specifically, that disconnect meant that later comparison tests would have to be far more complex in order to recognize and measure the increasing sophistication of high-performance motorcycles.

The raw, blustery, pure-performance Kawasaki Mach IV, an air-cooled, three-cylinder two-stroke, won “Superbikes 1973” fair and square. But did most readers really care?

Readers comb comparison tests to learn which motorcycles the editors genuinely liked for themselves. The ’73 comparo clearly answered that question. The editors were dazzled by the Kawasaki Z-1 (which finished second) and the Ducati 750 GT (fifth). The Z was the finest, latest, fullest expression of comprehensive Japanese engineering and the transverse-Four concept, but the Ducati had achieved parity as a favorite by using a 90-degree-Twin format. The editors noted that the Ducati 750, like the Z-l (and Honda 750), had been “cruelly restricted” by the narrow design of the test. The 750 GT “was the bike everyone wanted to ride home, points totals or no,” they said. That conclusion validated Ducati’s V-Twin layout as much, if not more, than victory at Imola.

The Ducati proved that the transverse-Four simply represented one-but not the only-path to the future. With perfect primary engine balance, the 750 GT proved uncannily smooth and deceptively

___strong. Sure, the Duck

Sure, the Duck

fell 14 ponies short of the mighty 903cc Kawasaki, but out on the road, in a top-gear roll-on from 30 to 90 mph, the torquey 469-pound Ducati would “kill the 903,” which weighed 542 pounds.

In the end, the comparison test made editors into believers. Almost immediately, two of the three principal authors of the test bought the bike everyone wanted to ride home, and eventually, staffers would own about a half-dozen 750 Ducatis.

Ownership. Now that was the ultimate endorsement of the new Ducati V-Twin. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue