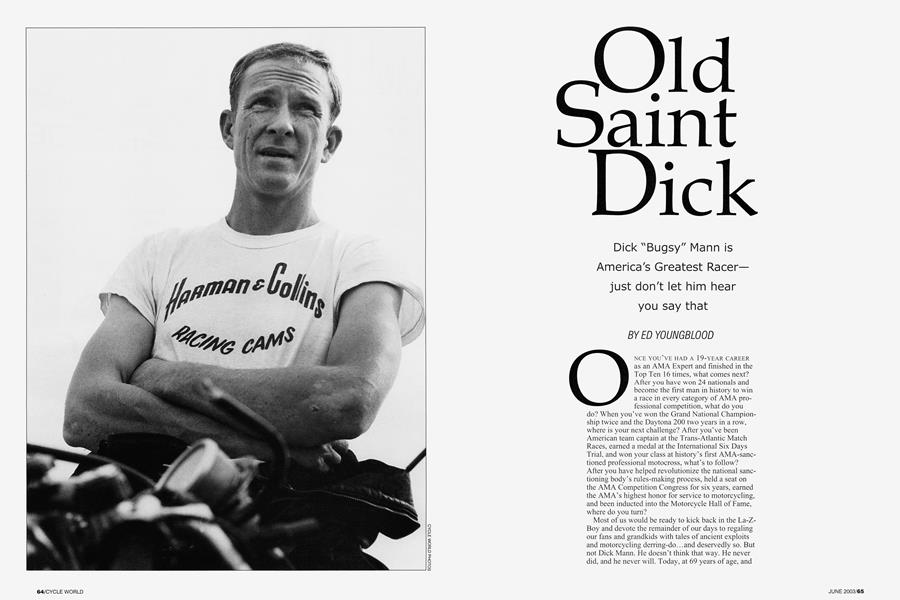

Old Saint Dick

FEATURES

Dick "Bugsy" Mann is America's Greatest Racer— just don't let him hear you say that

ED YOUNGBLOOD

ONCE YOU’VE HAD A 19-YEAR CAREER as an AMA Expert and finished in the Top Ten 16 times, what comes next? After you have won 24 nationals and become the first man in history to win a race in every category of AMA professional competition, what do you do? When you’ve won the Grand National Championship twice and the Daytona 200 two years in a row, where is your next challenge? After you’ve been American team captain at the Trans-Atlantic Match Races, earned a medal at the International Six Days Trial, and won your class at history’s first AMA-sanctioned professional motocross, what’s to follow? After you have helped revolutionize the national sanctioning body’s rules-making process, held a seat on the AMA Competition Congress for six years, earned the AMA’s highest honor for service to motorcycling, and been inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame, where do you turn?

Most of us would be ready to kick back in the La-ZBoy and devote the remainder of our days to regaling our fans and grandkids with tales of ancient exploits and motorcycling derring-do.. .and deservedly so. But not Dick Mann. He doesn’t think that way. He never did, and he never will. Today, at 69 years of age, and having battled a life-threatening disease, America’s most versatile, accomplished and enduring motorcycle champion continues to actively pursue the sport at a pace that would exhaust men half his age.

“I don’t relax. I go to sleep at night, that’s it. I don’t like to relax. I’ll have plenty of that...someday,” he says.

Bom in 1934 in Salt Lake City and raised mostly in Richmond, California, Mann discovered motorcycles through the acquisition of a secondhand Cushman scooter, which he used for his paper route, then traded for a brandnew BSA Bantam in 1949. Attracted to the weekly shorttrack races at Belmont Speedway, Mann traded the Bantam for a 350cc BSA, then eventually got a full-blown Gold Star dirt-track racer. There was something then-and there is something still-about the San Francisco Bay area for producing great motorcycle racers, and at Belmont, Mann went to school with the best, battling it out for a place in the main event with the likes of Joe Leonard, Charlie West and George Sepulveda. Today, Leonard fondly recalls, “I remember this little bright-eyed kid on a 350 BSA. He had about half the motor of everyone else, but he tried hard, he was really good, and sometimes he would make the main.”

Dick shared his experience and taught me how to set goals. He didn't have a lot to say, but when he did, you listened, -Kenny Roberts

Having Joe Leonard declare you “good” would be praise enough for most, but Mann, in characteristic modesty, professes otherwise. He says there are two kinds of riders: those with natural talent and those who have to leam the trade. Talented guys-Dick Dorresteyn, Eddie Mulder, Kenny Roberts-are few and far between, and Mann never counted himself among them. He surely had more natural ability than he will admit, but he became a racing legend through determination, hard work and countless hours on the road. The underdog status he got used to at Belmont seemed to follow him through much of his career. Mann was one of the few riders (Mert Lawwill another) who built, raced and maintained his own equipment, and rarely did he have a first-class ride. Knowing the tedious hours that went into engine work and chassis setup, Mann built his machines to handle well and finish the race, at midpack if necessary. He says, “My bikes were more like workhorses than racehorses. You have to finish the race to earn some money, much less win.” In fact, Mann was one of the last of America’s working-class racers who, like his friends Neil Keen, Darrel Dovel and Babe DeMay, actually made his living and fed his family with the hard-earned winnings from local tracks across the nation.

Although his career is commonly linked with BSA, “Bugs” (not even Dick is sure of the childhood nickname’s derivation) raced anything and everything, and won championships on more brands than any other rider. Mann’s winning mounts included BSA, Matchless, Yamaha, OSSA and Honda. Though he was a big four-stroke Single specialist early in his career, he later became the first man to win an AMA national aboard a two-stroke. He won non-nationals on Bultacos and Parillas, finished second twice at Daytona aboard Harleys and completed his final full season of championship racing aboard a Triumph.

Over such a long and varied career, it becomes difficult to identify Mann’s greatest moment. Some think it was at the Ascot TT in 1963 when he rode the grueling 50-lap event with a wound in his groin the size of your fist, not only winning but capturing the AMA Grand National Championship by a single point over George Roeder. Others believe it was the day in March, 1970, when he nursed an ailing Honda 750 Four to victory in the Daytona 200, giving Honda its first major American success and relaunching his own career. Conventional wisdom had declared Dick Mann over the hill by the close of the 1969 season, and no one would give him a ride except for Honda’s Daytona one-shot. But even then, Mann was selected as the sole American rider only so Honda could be politically correct, because its hopes were really placed on three British imports-Bill Smith, Tommy Robb and Ralph Bryans-all of whom blew up or turned their mount into a smoldering pile. Following the Daytona victory, BSA couldn’t wait to re-sign Mann to its factory team, and aboard one of their big roadracing Triples he delivered two of the best seasons of his career. He won Daytona a second time, rolled out legendary duels with world champ Kel Carruthers, and gained international acclaim at the Trans-Atlantic Match Races in England-all the while racing against a new generation of hotshots almost young enough to be his sons.

Those who raced against Dick Mann-from Bill Turnan in the 1950s to David Aldana in the 1970s-express awe at his toughness and determination. Once he raced at Watkins Glen with a freshly broken collarbone. Friend Digger Helm says, “He had a bone sticking through his skin, but he just taped a sanitary napkin over it and raced anyway. At the end of the race his T-shirt was red with blood.” In fact,

Bugs is one of the smartest peopl I've ever known.

-Mert Lawwill

Mann raced much of the 1966 season with a broken collarbone, held together with a pin that stuck out through his shoulder and a hole cut in his leathers. Then there was the time at Sacramento in 1963 when Johnny Hall taped Mann’s broken left hand to the handlebar so he could race, and again at Sacramento in 1970 when the On Any Sunday cameras recorded Mann cutting a cast off his broken ankle so he could boot up and eam a place in the main event.

By 1975, all of the great racers that Mann had grown up with had hung up their leathers, but Bugs was looking for new challenges, riding motocross and earning, at the age of 41, a bronze medal in the grueling International Six Days Trial. “I rode 180 miles one day without ever getting off the motorcycle,” he remembers. “I didn’t have anything to eat or drink, and I didn’t take a leak the whole day!”

By the early 1980s, a vintage motorcycling movement had begun in America, and Mann was at the forefront, organizing an annual dirtbike rally and helping write rules for the California Vintage Racing Group. In early 1989, a number of the regional vintage racing enthusiast organizations consolidated under the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association. AHRMA had previously been largely focused on roadracing, but Mann and several of his friends pushed for the creation of a vintage MX program. AHRMA Chairman Fred Mork says, simply, “Dick Mann is solely responsible for the vintage-motocross movement.” Mann recoils from this kind of exclusive recognition, and is quick to assert, “AHRMA’s strength is in its great depth of volunteers. It has succeeded through the dedicated work of hundreds of volunteer leaders throughout the nation. No single individual has made it happen.”

Regardless of where credit is due, AHRMA has grown to 10,000 members, half of whom are primarily interested in motocross, and among those who keep the organization

going are Dick and his wife Kay. Mann still travels in the neighborhood of 50,000 miles a year, attending AHRMA board meetings and consulting on the design of motocross tracks suitable for vintage machines. “What other two-time Grand National Champion do you know who will ride around on a lawn mower for three days to put on an amateur motocross for 30 guys?” asks one AHRMA member.

He was so much better than the rest of the Americans. Dick was surely one of the better riders I raced against during my first time in the States.

-Torsten Ha 11 mai

Mann also has been instrumental in the development of a national vintage-trials program, and in 1997-along with the late Leroy Winters-helped launch a national vintage-enduro series. He says, “Those not involved sometimes confuse vintage competition with jalopy racing. It is anything but. The machines these people ride are beautiful works of art. They are true racing machines from a bygone era, and it is the mission of the vintage movement to keep the bikes, tracks and rules of competition as faithful to that era as possible.”

Providing a supply of race-worthy museum pieces is one of the ways Mann pays his bills. He assembles eight to 10 motorcycles per year, most of which are big British and Swedish four-stroke Thumpers. These are not restorations to stock, but true competition machines, set-up just as Mann and other racers prepared their own bikes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A Dick Mann-built motocrosser or trials machine is a highly prized motorcycle. About 70 have been built and sold to date, and Mann always has a waiting list of more than a year. Collector John Sawaski says, “You never see a Dick Mann machine on the market. Owners hang on to them because they are beautiful, and because nothing else works as well. The engines and gearboxes are superbly built. They contain a lifetime of Dick Mann’s experience, and work far better than they did when they were brand new.”

Dick Mann was and is the Michael Jordan of our sport. -Jimmy Odo

I took Dick cowtrailing on my trails, the ones I rode almost eve but Bugs was so fast every 5 or 10 minutes to wait me to catch up. -Gary Nixo

In July, 1999, Mann was diagnosed with throat cancer, and the disease, plus a radical regimen of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, nearly killed him. At age 65, he confronted the ordeal with characteristic toughness and determination. Today, Dick is riding again, and as devoted to the motorcycle sport as ever, spending up to 10 hours per day in his shop building vintage racers, or long hours on the road on behalf of the vintage-motorcycle sport. He is a true American legend with a worldwide following of devoted fans spanning three generations. It seems that everything he has done with motorcycles he has done well, with one exception: Mann has never worn his celebrity well. To him, it seems an ill-fitting suit tailored for someone else. Despite his huge following and a lifetime of achievement, he remains humble, selfeffacing and sometimes painfully shy.

In fact, it is probably that humility and self-effacement that keeps him away from the La-Z-Boy. How can he possibly rest on his laurels when he fails to acknowledge that he even has any? Dick Mann always cared more about motorcycling than he did about himself, his fame or his image. That’s just how he was. That’s how he is today. □

President of the American Motorcyclist Association from 1981-99, Ed Youngblood recently authored Mann of His Time, a biography of Dick Mann. It is available from Whitehorse Press, 800/531-1133, www.whitehorsepress.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue