WES COOLEY AND THE GREAT FIM AFFILIATION CAPER

The Agreement Between Two Opposing American Organizations to Jointly Affiliate With The Governing World Body Of Motorcycling May be One Of The Best Things Ever To Happen To Motorcycle Racing. But Dissension And Power Politics May Doom The Effort To Bridge Two Worlds. It Is Time That We Look Behind The Scenes...

DAN HUNT

PART I: SKIRMISH IN YUGOSLAVIA

CHANCES ARE that you may have heard about an agreement between the American Motorcycle Association (AMA) and another U.S. organization which represents the world governing body of motorcycling and international competition.

Very good, you say. Does that mean we'll get to see more races pitting grand prix stars like Mike Hailwood against AMA stars like Cal Rayborn and Gary Nixon?

And does it mean that a racer will have the alternative to pursue his sport in the informal atmosphere of small FIM-oriented clubs without the threat of being banned from AMA racing?

The answer is yes to both questions. Spectators could benefit from the inter nationalization of big-time motorcycle racing, and racers could be guaranteed they will continue to have more alterna tives to participate in motorcycle sport than the AMA is able, or willing, to provide.

But the "yes" comes with two big "Ifs":

-If both the AMA and this other group, The Motorcycling International Committee Of The United States (MICUS), wish to continue honoring the agreement, now that they have made it. Unfortunately, there is a chance that the AMA may change its mind and back out.

-If both groups can show enough maturity to demonstrate to the govern ing world body, the Federation Inter nationale Motocycliste (FIM), that they are qualified to jointly represent the United States in international dealings. But this question is also in doubt.

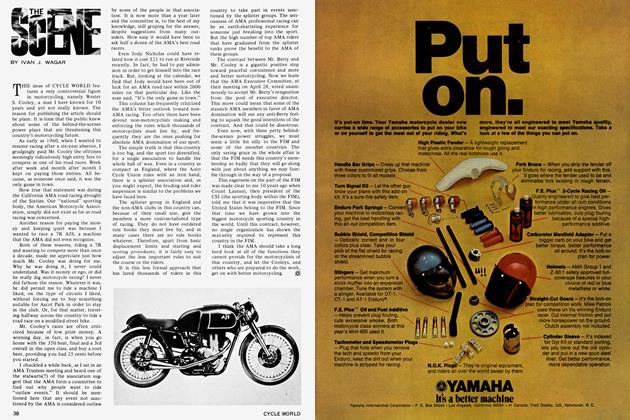

On the agreement appear the signa tures of Wes Cooley, as president of MICUS, and William Berry, who at the time of the agreement was executive director of the AMA.

Everyone should know by now what the AMA is. The AMA, like Wes Cooley, is an object of frequent excoriation. But at the very least the AMA is the largest and most powerful sanctioning organi zation for motorcycle racing in the United States.

The AMA is far from being inter national, however, in scope, orientation, sympathy, tendency or fact. That is where Wes Cooley steps in, for MICUS (deprecatingly called "Mucus" by its detractors) is the United States' tie with international motorcycling. It is the U.S. sanctioning arm of the FIM (Feder ation Internationale Motocycliste), under which the world motocross, road racing, and speedway championships are run, among other things. MICUS is to the United States what the CMA is to Canada and the ACU is to Great Britain.

If you, an American, wanted to enter an FIM event like the International Six Days, the "Scottish," the Isle of Man TT, or a European motocross, you would do so by obtaining an interna tional license from MICUS. More re cently, if your desire was to compete in the International class of the Inter-Am motocross series against world stars like Joel Robert, Bengt Aberg or Dave Bick ers, you would also apply to MICUS for International classification.

Why then should the AMA and MICUS get together to sign a piece of paper? Until recently there has been little direct need for an agreement be tween the two groups. The majority of the professional riders in the AMA have little or no interest in foreign competi tion. MICUS-affiliated groups, such as the ACA (Cooley's own group), Bob Hicks' Intersport in New England, the AFM (a California-based road racing club), the AAMRR (an Eastern road racing club), and PARA (a Midwest trials and scrambles club), have been able to get along without signs of friendship from the AMA, and perhaps have thrived from enmity in much the same way the Christians thrived on martyrdom. A little understanding would have helped, as the AMA has given many a good shafting to those of its flock who dared to participate in events put on by MICUS affiliates. This is, of course, whenever the AMA could get away with it, as certain states offer legal tools (i.e., the Cartwright Act in California) which deter the AMA from wholesale application of such idiotic monopoly.

Lately, however, the AMA has had to acknowledge the outside world. Interna tional Speedway stars have raced in AMA professional short track events. More and more foreign riders come to Daytona every year. And our best do mestic AMA road racers were weaned in the AFM, ACA and the AAMRR. The AMA, indeed, has finally admitted that motocross exists and has scheduled three national championship events this year. As the development of motocross in this country has occurred from out side rather than from within AMA ranks, it is plainly evident that the entry lists must be comprised in good part of riders who regularly compete in what the AMA terms "outlaw" events. If the AMA is to get good crowds, how in the hell can you suspend those "outlaws," particularly when they have so much spectator-drawing power?

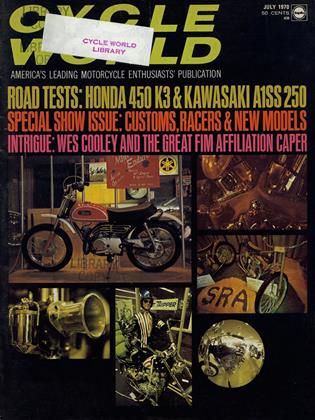

So last Autumn, the Three B's of the AMA-William Berry, President William Bagnall and Vice President Michael Bondy-went to Europe. And Berry went on to the FIM autumn congress in Yugoslavia. They had been instructed by the AMA executive committee that Berry's trip was a fact-finding mission, and he was not to enter into an agree ment without further committee review and approval. But, once in Europe, Bagnall "authorized" Berry to consum This is a photograph of the MICUS/AMA agreement made by Wes Cooley and William Berry in Yugoslavia. The chain of events that led to its signing are curious, but it is a step in the right direction-to link two worlds of motorcycling, yet permit each to retain its own identity.

mate a deal if it was to the benefit of the AMA.

The way had been paved by Bondy, who had lobbied with the FIM’s vice president, Emil Voerster. Voerster indicated he would support a move to oust MICUS, the present U.S. affiliate.

But Cooley had gotten wind of the AMA mission. So he arrived in Europe five days before the congress to do his own lobbying to protect MICUS. He received support from his old friend, Baron von Essen, an influential deputy vice president of the FIM, and fron the Belgian and Swedish representatives.

Cooley had already charmed the snooty Russian delegation during a sidetrip to Spain the previous year by jumping into an amateur bullring and running several straight passes on a young bull that had been wreaking havoc among the other erstwhile toreadors of the day. (“I was so scared I couldn’t stop,” he explained, laughing.)

When Berry arrived in Yugoslavia, and attended a speedway meeting prior to the FIM congress, Cooley walked across the infield, greeted an aloof Mr. Berry and invited him to lunch as his guest. It was a gesture which few of the protocol-conscious international delegates there failed to notice.

The important thing to note here is that Cooley, one man representing MICUS, has better rapport with the Europeans than all three of his AMA counterparts put together. And he is a superb tactician.

Realizing that having half the apple was better than losing the whole thing, Cooley conferred with the president of the FIM. He secured an informal agreement that if he and the AMA could reach a detente for the period of one year, MICUS could share equally with the AMA in the forming of a new arm of the FIM for America. It would be called the USMA (United States Motorcycle Association), but neither the AMA or MICUS would lose their respective integrities. The USMA would have two votes in FIM affairs, the AMA having one, MICUS having the other. Standoffs would be settled by the FIM president.

Result: Berry never got to the floor of the FIM congress.

Result: Berry attended two FIM caucuses as the “guest” of Wes Cooley.

It was now up to Berry. Apparently, he felt the time was ripe to get something out of the trip, even if it was only the other half of the apple.

Result: Berry and Cooley signed an agreement which established, on a oneyear trial basis, several points of cooperation between the AMA and MICUS. One point was that AMA and MICUS could co-sanction professional races in the U.S. Another was that AMA professional riders could, directly through the AMA, apply for an International license from the FIM (cost: $15).

Even if the agreement was made without AMA Executive Committee approval, it was a giant step forward. Two motorcycling factions in the U.S., who have often been bitterly opposed, were agreeing to cooperate for the betterment of the sport.

However, the outcome of this overseas power play has a curious note to it. It wasn’t necessary for the AMA to send Berry to Yugoslavia. It might have made the same agreement with Cooley right here in the United States. At less cost. But apparently some members of the AMA had been gambling for the whole apple.

Had the AMA and the FIM come to a direct agreement, ousting MICUS in the bargain, there would have been a rapprochement of U.S. and European motorcycling. But it would have been of dubious benefit. Cooley and a few thousand MICUS-affiliate riders would have been frozen out. Without the prestige of FIM affiliation, clubs like Intersport, AFM, ACA and AAMRR could conceivably shrivel away. In one fell swoop, the AMA would have destroyed MICUS, which is one form of leverage that these clubs have over the AMA. Assuming that traditional AMA attitudes would prevail, the AMA, suddenly all-powerful, would have done next to nothing with its new tie (there are some influential AMA stalwarts who are unaware, for example, that the U.S. fields a large team each year in the International Six Day Trial). This country’s move away from motorcycle “isolationism” would have been set back 20 years.

Even now, with the AMA/MICUS agreement signed, there are few AMA executive committee members who can claim that they have seen a copy of the agreement. Berry reported on his mission to the committee after he returned to the United States, but no one there thought to ask to see it. They may see it published here for the first time.

As for the non-AMA faction, some of its members think that Cooley “sold out” by signing an agreement with the AMA. Not so. In truth, he outmaneuvered the AMA. By giving them half the apple, Cooley saved MICUS and its member clubs from oblivion. For a little while, at least . . .

PART II: THE FIM SETS SAIL ON A STORMY AMERICAN SEA

IN the beginning, which dates back to the Fifties, there was the United States Motorcycle Club (USMC). As Cooley remembers it, USMC was the brainstorm of a man named Tom Galan. Galan has been characterized by some people in motorcycling as resembling a city-slicker of the type that country bumpkins should avoid when walking near the Brooklyn Bridge.

Somewhere Galan heard that the FIM was a good thing to tie up with. So he contacted them in Europe and asked for affiliation. A representative arrived from Europe to see if the USMC had proper facilities.

As Galan had no facilities, he used his insurance office as club headquarters to impress his visitors.

The USMC got the go-ahead to hold certain international races in the U.S., which would give USMC greater prestige. Enlisting further cooperation from

Bill France of NASCAR in putting on these events at Daytona, one of which featured Mike Hailwood, Galan’s club grew like topsy.

Roughly concurrent with USMC were other “splinter” groups: the already existing American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM), which evolved from the West Coast-based Grand Prix Riders Association; the American Cycle Association (ACA), which is Cooley’s own club; the AAMRR (American Association of Motorcycle Road Racers), formed out of one of the USMC chapters; the Pan American Racing Association (PARA), formed by Kansan Bill Grapevine to foster exchange activity between U.S. and Mexican racers; the Streeterville Scramblers, a gung-ho group of affluent types; and the North Carolina/Tennessee Racing Association, an aggressive, big-purse outfit run by a fellow named Red Nabors.

These clubs and the USMC were virtually ignored by the AMA and left to develop on their own.

Then Galan had the bad taste to remark in a USMC newsletter that his group would run right over the AMA. At this point the AMA monolith got a little stirred up and scared off a good number of riders who patronized USMC events by saying that they would never get to ride in an AMA event again. The other non-AMA clubs were shaken up, too. Galan dropped out of the picture and the USMC started fading.

We asked Bill France Jr. if USMC was the FIM affiliate. He said no, the USMC was only a club with permission to run a few international events, not the real affiliate. The question is academic, in a way. As it was the only group given power to run FIM events here, USMC was in effect the “ad hoc” FIM affiliate.

Why then, we asked France Jr., was it necessary to form MICUS?

If international events were to multiply in this country, he replied, we needed a group similar to the American automotive world’s ACUS, a branch of the FIA, which sanctions world GP events; USMC was only a single club, and not an effective one at that. So some tentative meetings were held, including Cooley, the USMC, AAMRR and the other clubs. A few years passed with nothing being done.

Then in 1962, three of France’s associates became the nucleus of the first “official” FIM affiliate—named the International Motorcycling Board of the USA, Inc. They were: William Spear, president; Howard Sluyter, vice-president; and honorary secretary and treasurer, Rene Dentan, who would be quite useful, for, as president of American Rolex Company, he commuted regularly to Geneva, Switzerland, spoke French, and therefore could communicate personally with the FIM on his business trips. Incorporation took place

in September 1962 in Delaware, that state offering no particular advantage other than a set of liberal corporation laws for non-profit groups.

Three different names appear on the original charter-R.G. Dickerson, J.A. Kent, and Z.A. Pool III, all of Dover, Delaware; these men are probably lawyers, or legal proxies for Spear, Sluyter and Dentan, who did not reside in the state. Proxies hold the original incorporation meeting, then transfer the directorships to the proper people at a subsequent meeting.

The bike clubs were brought into the Board as members, and could voice their needs by appointing a club representative to the board.

As the original name was somewhat of a mouthful, even when reduced to initials, the group changed its name on Feb. 19, 1963 to Motorcycling International Committee of the United States, or MICUS.

So MICUS carried on. USMC, the club which had the original “tie” with Europe, sagged even further and declared bankruptcy six or seven months after MICUS incorporation.

In those days, the AMA people used to get uncommonly bitter when MICUS’ name was mentioned, for some of them apparently had an eye to securing the FIM affiliation.

From several sources, some of which are contradictory, it is only possible to say that the AMA apparently made overtures to the FIM before MICUS was formed. The FIM replied that the USMC was functioning as the FIM’s sanctioning arm in the United States, and there could be only one such group serving the FIM here at any one time. But the FIM added that the AMA would be considered for affiliation, if the USMC should ever go out of business.

Imagine AMA’s surprise when MICUS appeared on the scene and USMC went bankrupt months later! Somebody had shut the gate on poor old Columbus.

The irony of this! MICUS’ operation was indirectly supported by the AMA’s biggest promoters—the Bill Frances Sr. and Jr., of Daytona Speedway. MICUS’ “headquarters” was now in the Speedway office, and Russ Moyer, Daytona press secretary, handled MICUS’ licensing and sanctioning paperwork.

It seems strange that the Frances would put themselves in such a position with the AMA. On the other hand, we reason, the AMA of that period was even more clubby, chauvinistic, bush league and inefficient than it is now. As such, it was more certainly incapable of fostering international competition on a big time scale than it is now. Perhaps the Frances were of the same opinion.

At any rate, MICUS carried on, but at a somewhat static rate of growth. I recall tales of woe from racers I knew during the early Sixties who tried to get international licenses to compete overseas, and were met with such slow service that they took matters into their own hands and faked it.

Then William Spear resigned as MICUS’ president. Bill France Jr. still thought there might be something in it and took over the presidency. But he soon decided he wanted out, as did the other two directors, Sluyter and Dentan. None of the three had enough time for the job, France said.

In 1967, France called a meeting of the member clubs in Atlanta, Ga. Wes Cooley says that France had telephoned him before the meeting and asked Cooley to take over, because it was costing France too much money and time. Cooley said that he would accept, but asked that the other member clubs be present so they would not feel slighted and pull out.

When the meeting was called, all the clubs were notified, but only the AFM, ACA, AAMRR and PARA representatives appeared. Grange’s group and the Streeterville Scramblers had disappeared.

Cooley represented the ACA as its president; Fred Otto represented the AAMRR as its president; Grapevine represented PARA as its president. As for the AFM, it was represented by John McLaughlin (road racing buff and former Catalina winner), who was delegated as the AFM representative for that meeting, although he was not actually a member of the AFM at the time.

There are conflicting reports as to what actually transpired at this meeting, which, as we shall see, had grave consequences.

Wes Cooley claims that when France Jr. and his associates resigned, they named him president of the governing board of directors and told him to appoint two other board members. Cooley further claims that McLaughlin, Otto and Grapevine were named as club representative directors, rather than members of the governing board of directors.

A copy of the MICUS by-laws would seem to support Cooley’s claim, as Article 6 lists “Permanent Director” and “Representative Directors.” A photocopy we have of the minutes of that meeting would also seem to support his claim.

But McLaughlin, Otto and Grapevine claim that there is no distinction between the two, and McLaughlin’s lawyer contends that such a double corporate set-up would be illegal.

McLaughlin says he was made the “real” secretary-treasurer, and Otto and Grapevine were made the “real” vicepresidents.

The only thing for sure at this point: Cooley received the MICUS charter, application forms, etc., and a check for

$1000 from the old MICUS bank account.

The latter was delivered to McLaughlin to open a new bank account, which required the signatures of both McLaughlin and Cooley when a withdrawal was to be made.

Whether McLaughlin was the real secretary-treasurer or not, he, in fact, was told to keep MICUS’ books and make deposits of sanction monies and license fees. And he did so, for awhile.

But a problem arose. Cooley asked McLaughlin to let him see the books in late 1968. McLaughlin, Cooley says, arrived at his house with a single sheet of paper on which he had written names, check numbers and deposits. In Cooley’s opinion, this was not the way to keep a set of books.

“So I took my CPA, John Harris, over to see McLaughlin and tried to get a set of books out of him. He had none,” Cooley says.

Cooley decided to keep his own books and open a new bank account for MICUS. Why didn’t he tell McLaughlin this? He didn’t want to hurt McLaughlin’s feelings, he said. And then he would tie up loose ends when someone from the AFM eventually replaced McLaughlin.

This apparently remained a moot point with McLaughlin until last fall, when he decided to sue Cooley. The Inter-AM, sanctioned by MICUS, was in full swing, but John hadn’t received any sanction fees to bank from Cooley for quite some time.

He demanded to see Cooley’s books. Cooley claims that he told McLaughlin that the books could be viewed at his lawyer’s office. But McLaughlin says he never saw them. At any rate, the latter filed suit.

Elsewhere in the far but thinly flung world of MICUS, all had not been well. Going back in time a bit, Fred Otto, representing MICUS in New England, took sanction money from promoter Bob Hicks for the first international motocross at Peppered in the fall of 1968. But Otto, says Cooley, did not even act as a rep at Peppered. Hicks didn’t have so much as an FIM rulebook to go by. Cooley complained to Otto and said Otto’s reply was that he didn’t know anything about motocross, because he was, after ad, a road racer. Oh. But Hicks said he’s been quite happy with MICUS: “They don’t interfere.”

Cooley continues, “The same thing happened with Bid Grapevine and John McLaughlin. Not one of these gentlemen attended their FIM meets. McLaughlin,” he said, “never went to one of the California Motocross Club events, although sanction money had been paid to MICUS.”

So, last year Cooley sent reps from his own club, the ACA, to each of the Inter-Am motocrosses to help with the

running of the event. Cooley notes, “That’s another thing McLaughlin is complaining about—that we spent money to send people places—which we did. We had to.”

In another move against Cooley, McLaughlin called a meeting of the MICUS board of directors, the intent of which was to oust Cooley from MICUS. Cooley shunned the meeting, contending it was illegal. Otto, Grapevine and McLaughlin voted Cooley out.

Cooley makes these points about that meeting: 1) Under California code, directors must be notified five days prior to the meeting. Cooley contends he received his notice only one day prior to the meeting; the actual date on the letter is only five days before the meeting. 2) As chief executive officer of MICUS, Cooley says he notified every member of the corporation by registered telegram on the day he received McLaughlin’s letter that this was an illegal meeting. 3) In the corporation by-laws, it says that the only officer who may call a directors’ meeting is the president (i.e. Cooley). Cooley says McLaughlin was a members’ board secretary-treasurer, not a member of the governing board, and should not have called the meeting.

In short, the whole thing is a bag of snakes. McLaughlin’s suit has yet to come to court. But meanwhile, he notified the FIM that MICUS’ address was changed, following the emergency election meeting on Nov. 22, 1969. So Cooley stopped getting his mail from the FIM, and McLaughlin started getting it instead.

Cooley now intends to file a crosscomplaint against McLaughlin and the others.

One by-product of the address change: Motocross rider Russ Darnell, who applied to Cooley for an international license, arrived in Europe a few months ago, having arranged his starts for this season. But he could not ride, for his license is not valid, apparently due to a mix-up in paper work.

A further by-product is yet to come. Cooley feels that there is no way he can lose the McLaughlin vs. Cooley suit, but if by some strange chain of events he did, he feels that it will destroy MICUS for good.

“Nobody else in MICUS has any rapport in Europe. All of them have an absolute vendetta against the AMA, which I think overrides their ability to compromise with dignity—not give everything away-and try to work something out with the AMA.”

If Cooley wins, MICUS will keep half the apple for some time. It is uncertain what will happen if he loses. Even before the decision is made in court, the FIM might get fed up with the whole mess and deliver the affiliation to the AMA in toto. (Continued on page 66) Continued from page 65

PART III: "WHAT IS A WES COOLEY?"

IF you you have may stayed have guessed with us that this this far, story is not entirely about Wes Cooley.

But Wes babe just keeps popping up in the middle of it all, like a cork in a storm-tossed sea. Is this phenomenon mere random action? Or, may one ask, in a more indignant stance, is Mr. Cooley even qualified to make frequent appearances in an area so important to motorcycling?

Examining the Cooley phenomenon from a psychological point of view, we can say, conservatively, that he is “controversial.” More extremely, we can say that he is hated by many. Somewhere in the middle, where a rational man would assume he could find the truth, we can say that he is the subject of a great deal of bad-mouth and that he may have

been slipshod in his execution of some MICUS affairs.

The rational man might therefore conclude that the Wes Cooley phenomenon, examined for its surface aspects, carries a somewhat negative cast.

But we can, and should, take this extremely emotional and negative tide of opinion against Cooley and examine it further. To do so. we might borrow a stock market concept called the “theory of contrary opinion.”

Stated simply, contrary opinion means that smart men should think about buying when the dummies are scared and selling out. Conversely, when the dummies are lapping up everything in sight, the smarties are pulling out, because they know the bubble is going to burst.

If contrary opinion holds true in Cooley’s case, he comes up smelling like a bed of roses. Particularly if you examine the underlying fundamental virtues of the man.

The important thing is that his detractors accord him a certain amount of attention. If Cooley ignores them, or shuns them, his detractors get even madder.

That makes us inquisitive. What is a “Wes Cooley,” and how did he get involved in motorcycling?

Wester Shadrick Cooley is basically a businessman. And if it is really true that money is how we keep score in America—as Adam “Money Game” Smith and Neil “Peaches” Keen say it is—then Cooley scores pretty well.

More crassly, he scores about a million bucks worth, an asset that varies daily with the up-and-down performance of “ICN,” a ticker symbol listed on the American Stock Exchange.

Cooley is an executive with ICN, initials for International Chemical & Nuclear (which Wes gauchly pronounces “nookeooler” in an attempt to hide his good breeding). And he owns a large block of that stock. Significantly, not one of his detractors can claim as much.

While the acquisition of money has acquired a malodorous taint in these idealistic times, an objective amoral look at the process of amassing a fortune would reveal that it requires intelligence, dedication, luck and a great deal of work. Being a little hardnosed doesn’t hurt, either. Cooley has what it takes on all five counts.

Some people would like to curtail his involvement in motorcycling. But they can’t seem to find his jugular. It is hard to apply motorcycle industry pressure to oust a man who doesn’t gain his living from the motorcycle industry.

Some people say Cooley is in motorcycling for an “ego trip,” implying a negative connotation. The term “ego trip” strikes me as a rather dull barb. Most strivers—be they executives, politicians, motorcycle racers or writers— need to be sustained by some such thing if they are to survive.

Cooley himself says he is in motorcycling for kicks. He enjoys it, believes in it, and wants to see it grow. Viewed against his past, Cooley’s involvement seems quite in character.

On the other hand, Neil Keen, who as president of a professional bike racers’ group had dealings with Cooley, has double-contrary opinion. Cooley and Les Richter of Riverside Raceway assembled a group of racers and industry people to inform them they were going to throw an international grand prix race. What galled Neil, then? Cooley and Richter wanted Keen and his boys to race for nothing.

(Continued on page 69)

Continued from page 67

In typically eloquent fashion, Neil commented: “I would feel much better about Cooley if he would admit that he is in racing to profit from it. Then he would be believable. But no, he says he’s in it for the good of racing.”

As for the more tangible Wes Cooley, he epitomizes the native Angeleno. His age—38—may be a surprise to those who have met him, for he looks to be in his late 20s. He is in excellent physical condition. In spite of a Lear-Jet business schedule that drives him at 60 to 70 hours a week, he manages to get out riding every so often on a 250 Husky. He belongs to the Prospectors (ironically, an AMA club) and we saw him on the starting line of the Hi-Mountain Enduro only a few months ago.

The other part of his youthful demeanor derives from his style—middle be-bop, rock-and-roll, Korean War erabackswept hair, almost a ducktail treatment, but narrowly avoiding hipness or zootiness. To see him either in bellbottoms or, at the other extreme, in a flashy square man’s suit with diamond ring would be travesty and it wouldn’t fit—like King Kong in a body stocking. His is the middle road, the California business-guy look, the face you don’t remember too well until you look it up after signing his contract. It’s a proven marketing technique, and if you don’t believe it, ask some of the men in the motorcycle industry who continue to use that same era approach quite effectively—Frank Cooper and Don Brown, to name two.

Now a history of Wes Cooley, by Wes Cooley.

His high school education consisted of a succession of prep and military schools, some of which I am familiar with first-hand and can attest to the manner in which they teach you about the bumps and grinds of the real world, as well as getting you used to the idea of working your tail off, and instinctively telling who the liars and flakes are. Cooley’s introduction to motorcycling consisted of a Harley VL-74, acquired at the age of 16.

Then came 30 months of the military. Cooley’s athletic prowess (a 9.8sec. 100-yard dash and high school swimming records that still stand) paid off handily, and he qualified for a specialized training course which was sort of a pilot program for what is now called the Green Berets.

This consisted of paratroop school at Ft. Benning, psychological warfare and ranger training at Ft. Bragg, and FBI school at the Pentagon. Wester Shadrick Cooley emerged from this ominoussounding 20th-century-man educational series as a full special forces agent for the Government. Fortunately, he didn’t have to use any of it and was able to return to civilian life as the Korean War petered out.

(Continued on page 71)

Continued from page 69

He qualified for a scholarship to El Camino College, was a straight-A student, and president of his fraternity. Then on to USC, where his record was equally as good. He graduated with a B.S. degree in Economics and Marketing and an A.A. in Law.

It was during his USC period that Cooley was “drafted” into motorcycle politics by Joe Quaid.

Does anybody remember Joe Quaid? Don’t all raise your hands at once. Okay, you give up. Does anybody remember Pookie Baker? Ah, a few hands! If you were drooling over that chic series of Bultaco advertisements in CYCLE WORLD a few years back, therein was Pookie modeling. It was great stuff. Miss Baker also wrote and illustrated a travel series for CW in 1966. But back to Joe Quaid, who worked for Bultaco American during that period. He’s her husband. Now you’ve got it.

Before that Joe was also at USC with Wes, and they had been friends from their days at El Camino. Quaid, who was involved with the Grand Prix Riders Association, alias the American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM), talked Cooley into going to see a race “out in the desert.” It was a road race, with a gigantic 14-man entry. Oh, those struggling early days of American road racing!

Cooley was hooked, or “stoked,” as he puts it. He started scoring races, and soon was racing himself. Great fun, but Quaid, who was on the AFM board, had some plans for Wes, whose acumen for business and leadership (a USC senator, president of the Tro-Vets, not to mention the usual high scholarship) was already apparent.

The AFM was in trouble, and in the red. It owed an insurance company twelve or thirteen hundred dollars. The company brought suit and sought an injunction to stop the whole works until they were paid. Also, AFM’s officers had been too busy having fun and had forgotten about the annual amenities required by the Internal Revenue Service.

Would Cooley take over the presidency and help get them out of this mess? Cooley agreed reluctantly, apparently not having been informed about the full extent of the problem.

(Continued on page 73)

Continued from page 71

To cut it short, he registered as president of the corporation, non-profit in fact as well as in law, and in the months following worked out a time payment plan with the insurance company. He soft talked the 1RS into a more sympathetic position, with the proviso that the AFM might let 1RS take a look at the books periodically.

As time passed, everyone forgot his service. Cooley ran things his own way. The corporation setup—governing members of which Cooley was the kingpin, and elective board of directors, who gave suggestions which somehow were always shrugged off—was hardly conducive to good feelings. As Cooley prospered in his private business life, the rank-and-file started whispering that he must have been skimming money off the races and investing it in stock.

That is a rather absurd notion, one that could be expected from the corporals in the trenches who mutter sweet nothings in the dank night about their beloved general. Cooley puts it another way: you don’t skim a million bucks from a nickel-and-dime operation.

But eventually, some of the AFM boys decided they wanted to have their own racing club. Cooley didn’t much care, and even let them take the AFM name with them, although he retained the original corporation. Cooley renamed his group the American Cycle Association (ACA) and in subsequent years spread the GPRA/AFM/ finally ACA out of the road-racing-only picture and into short track, TT scrambles, motocross and speedway—some professional and some not. It was a rather impressive alternative program, considering the lack of variety in AMA offerings during those years. His present program involves the ACA summer series of weekly short track and TT races, 18 road races and 20 motocross meetings. During the Inter-Am series, when he has to do his MICUS business, the ACA becomes dormant.

On the negative side, as of late, come mutterings from riders and AFM people that he doesn’t use enough flagmen, or that he holds purses until the completion of the season, or that he pulls sneak plays on riders’ insurance, or that poor so-and-so didn’t get paid for the 12hours, etc. They are tenuous charges and many seem to evaporate when you go to the source. For instance, we went to the sponsor of two riders who allegedly had not been paid for their 1969 win. The sponsor told us they were paid. There was a delay, because the ACA awards banquet was delayed for about a month last winter while Cooley was in the hospital for an operation.

If Cooley has one major fault, it is this: He needs a full-time public relations man and paper pusher; his wife, Beverly, spends many hours per week on ACA affairs, as it is. Wes has a reputation for being short with people. At a riders’ meeting, he comes on like a drill sergeant. He sometimes misses appointments with people who are not going to take it lightly, and he can be very hard to reach when he needs to be. Men who have raced with his club say that he can act petty at times. Boom! Conflict. Misunderstanding. Bad-mouth.

If you can forget Cooley’s studied lack of flash, all these shortcomings remind us of a few eccentric millionaires we know. They also remind us of certain rank-and-file dealings we have seen go on in the AMA.

. . . Which gets us back to the original point. Where did Wester Shadrick Cooley get all that success?

It began with his education, of course. You study money to make money. Then you try to find a big wave and ride it home. Cooley never explained this during our interview, but we have a feeling that his intuition told him that people were going to need a lot of pills and stuff during the “Soporific Sixties.”

So he joined Hyland Laboratories (biologicals, diagnostics, etc.) as a marketing assistant to the vice president.

(Continued on page 76)

Continued from page 73

Then came two false starts: a car wash franchise in Torrance that bogged down in the recession of 1961, and a stint at legal underwriting with General Insurance Co., and a non-start with another. “It just wasn’t my bag,” he says.

Back to drugs. He went partying with an old USC crony, who used to enlist Cooley’s aid in passing courses. Next morning, his buddy, who was president of Allergan Pharmaceuticals, yanked him out of bed and told him to come to work, hangover or not. When Cooley joined Allergan, he was the sixth employee of six employees. Allergan grossed $80,000 annually. When he left about six years later (having nicely covered as assistant for a golf-loving vice president), Allergan was grossing $5 million and employed 250 people. Cooley’s life was becoming more comfortable.

And his capacity for work was noticed in 1965 by a visitor to Allergan named Milan Panic (say it “pahnish”). Panic, a struggling refugee from Yugoslavia with a language problem and an uncompleted education for a Ph.D in Chemistry, had some rare chemicals to sell. They were made by his own two-bit company (the stock sold at 25 cents a share in those days) housed in a small brick building in the City of Industry.

Panic wanted to hire Wes after they became friends. Wes was leery at first, because the only thing holding Panic’s International Chemical & Nuclear Corp. (ICN) together was so much financial chickenwire. Panic would acquire other two-bit companies with saleable products by trading some of his nearly worthless stock. Soon, however, Wes started taking notice, because, after only two years, ICN was trading at a new high of $11 a share. Ouch! And Wes could have bought 2000 shares when the price was only 25 cents!

In 1967, Panic persuaded Cooley to come to work for the gift of “a number” of ICN shares worth $11, and, of course, a fat salary. If you want to know exactly how many shares you can go ask a certain relative of a certain publisher of a certain motorcycle paper.

That relative worked at ICN and knew how many shares Cooley was given. So publisher and relative computed out what Wes would be worth today. Then publisher ran it in his newspaper for funsies.

At any rate, Cooley had put himself in the right position at last, having had the brains and drive to be noticed. Suitably attracted, Lady Luck wailed on.

ICN bought another company called U.S. Nuclear and Cooley’s stock jumped to $38.

ICN bought Nuclear Science & Engineering and Cooley’s stock jumped to $70.

Then ICN bought Environmental Sciences, followed by Technical Associates, and Cooley’s stock went to $380 and split 2.5-for-1.

More building and buying, etc., and Cooley’s stock grew and was split 2-for1 (which fractions the price by multiplying the number of shares available, making it easier to buy and grow). Lately it has been holding moderately well in a generally dismal market. When the Dow Jones thundered down past 740, his paper worth probably dropped to about $750,000.

ICN itself grosses $82 million with net earnings of $5 million. Projected gross sales should easily top $100 million in the coming year, Cooley says. Panic, who had to work in the steel mills when he arrived in the U.S. in 1959 because of his limited English, is now worth about $7.5 million—not bad for 11 years work and for a man who is only 41 years old.

Cooley says Panic is the original capitalist, the guy who gets all sentimental at the office Christmas party and says, “You should get up in the morning and thank God in his act that you can go to work.” Or, “Yes, I was born in Yugoslavia, but I was born American.”

Naturally, when everybody found out Cooley had all those paper profits, they all had another reason to throw stones.

“It must be jealousy,” says his leggy wife, Beverly.

Thinking positively for a moment, the AFM might not have survived if Cooley hadn’t given of his time and talent. There might have been no road racing in California for 10 years. And if there had been no road racing in California, there might have been no Grants, Baumanns, Pierces or Rayborns to grace AMA starting grids at Daytona or Louden. All of these pavement masters cut their teeth in AFM and ACA events.

Men who arrive at the top to run things have their shortcomings and idiosyncrasies. They aren’t necessarily crowd-pleasers, for they aren’t part of the crowd. Luck plays a part in their success, admittedly. Wes Cooley may not have singlehandedly been responsible for the survival of the AFM, the flourishing of the ACA, or the growth of Hyland, Allergan and ICN. But can anyone believe that his successful association with these enterprises resulted from pure chance?

Now that we know a little more about the historical side of Wes Cooley, we can well understand how he saved MICUS from the AMA onslaught in Yugoslavia.

(Continued on page 78)

Continued from page 77

PART IV: THE END GAME

IN there this world, are players. there Both are pawns are in and the game, but one is moved and the other makes the move. Both arrive to the end game and both take part in the checkmate. The players either win or lose. The pawns do neither, they are only there to be used.

Assuming that this parallel is applicable to the complex set of machinations we have described so far, then we may properly say that we are in the “end game.”

It’s a three-sided game to all outward appearances. John McLaughlin vs. Cooley/MICUS vs. AMA. That’s strange. The usual adversary game has only two sides . . .

End play is centered around the internal strife besetting MICUS. Divide your enemy, the old saying goes.

But the question asks itself: who is dividing MICUS? It appears on the surface that the division is self-inflicted. Yet, the AMA would gain much if MICUS were rent asunder—exclusive FIM affiliation and no more competition. AMA would have things its own way: it would take over the Inter-Am series, all licensing of riders who wish to compete abroad, sanctioning of international speedway events, road races, motocrosses, etc., and the choice of U.S. entries to the ISDT. Using the aforementioned art of contrary opinion, then, it would seem likely that anyone in the AMA hierarchy who desired this to happen would be delighted to give the division of MICUS a helping hand, even if the division was primarily self-inflicted.

The division of MICUS arises from the McLaughlin vs. Cooley affair. John McLaughlin, staunchly non-AMA, is suing Wes Cooley, staunchly but more diplomatically non-AMA.

As related to us by Paul Garber, acting as McLaughlin’s lawyer in the action, the suit covers three points, based on California corporate code:

1. McLaughlin seeks to compel Cooley to surrender the books of MICUS for inspection, under Section 3005 of the code, claiming that as an officer and director of MICUS, he has a right to see them, and has been denied that right.

2. Making both MICUS and Cooley defendants under Section 811 of the corporate code, McLaughlin alleges that Cooley collected monies for licenses and race sanctions and failed to deposit them to the authorized corporate account at the United California Bank of Monrovia.

3. Cooley is sole defendant in yet another action based on Section 820 of the corporate code, which lawyer Garber describes as a charge that Cooley has committed acts “tantamount to corporate fraud.” The action seeks $50,000 punitive damages.

If McLaughlin wins on all points of his suit, Cooley would have to surrender all MICUS documents and records, and the court would appoint a CPA to audit MICUS books. Further, Cooley would be removed from MICUS and no longer be a director, and would have to pay attorneys’ fees for the suit, as well as making restitution for any “fraud” that was proved, and pay $50,000 in punitive damages.

Attorney Garber thinks McLaughlin has a good case. And Cooley thinks likewise about his own chances; he says he has the necessary documents, including the minutes of the Atlanta meeting, to prove that neither McLaughlin, Otto or Grapevine were made members of the governing board of MICUS. The outcome of the case seems to hinge largely on proof of this fact one way or another.

It would be useless to speculate on the outcome of the trial; Cooley has been subpoenaed, but has not yet given his deposition, at which time preliminary evidence would be presented.

However, beyond the immediate outcome of the impending trial, the suit has some interesting implications, which we discussed with Attorney Garber.

For instance, wouldn’t McLaughlin’s suit, successful or not, endanger MICUS’ affiliation with the FIM?

Garber said yes, there was some danger of that, but that it was a “risk that we’re prepared to take.” He also commented that if McLaughlin could prove that himself, Otto and Grapevine were directors of the governing board of MICUS, it would be grounds for invalidating the agreement Cooley signed with Bill Berry of the AMA during their trip to the FIM congress. For Cooley thus would not have had the approval of the MICUS board to take such an action.

On the other hand, McLaughlin himself feels that there is little risk in MICUS losing the FIM affiliation, but if it did, “the AMA would have to fight me on an anti-trust basis.” If the “present management” of the AMA succeeded in getting exclusive FIM affiliation, McLaughlin said, “they would let it lie. They wouldn’t do anything with it.” After he queried the AMA regarding formation of the co-affiliate USMA, McLaughlin added he received a reply stating that the AMA didn’t wish to discuss the matter. “Nobody seemed to know anything about the agreement,” he said.

Attorney Garber seems quite knowledgable about the inner workings of motorcycle politics (for instance, he was aware that the AMA had asked Executive Director William Berry to resign before that fact had become a matter of public record). Well, he should be, as he is also counsel for a magazine published by William Bagnall (president of the AMA). Further, he said he is handling McLaughlin’s correspondence to and from the AMA dealing with the formation of the USMA—the proposed joint affiliate to the FIM comprised of the AMA and MICUS.

So we asked Garber if invalidation of the Cooley-Berry agreement on MICUSAMA cooperation would not leave the FIM affiliation up for exclusive grabs by the AMA?

He said that such an outcome was possible, but that if it should happen, maybe it wouldn’t be a bad idea, in his “personal opinion.” The AMA, he explained, was a well-established organization in this country, and “at the boardof-directors level” had a good reputation for honesty and integrity. He also praised AMA President Bagnall as being an honest man, whom he had known for years.

Garber’s “personal opinion,” to which he most certainly has a right, gave this writer great pause, for it is ill-fitting that an attorney voice his personal sentiments in favor of the AMA to a member of the press—particularly when he is being paid to represent a man who is dealihg with the AMA as an officer/ director of MICUS-John McLaughlin.

Voicing such sentiments as he did, Attorney Garber no longer seemed to be meandering across the political chessboard like a knight or a rook or a bishop. He sounded more like one of the players . . .

PART V: EPILOGUE

THIS hasn’t has been it? If an the amazing reader will odyssey, have empathy with the writer’s task for a moment, he will realize what it is to walk through a confusing labyrinth of fact and fiction, in which the walls, floor and ceiling always seem to be moving.

From no one can he get the straight story. Nor can he find anyone who is fully informed on the matters discussed here. So he is left to grope around the outer passages of the maze, hoping that his path faithfully implies the dimensions of the hidden center.

The only conclusion to be drawn from our trip is that it forms a dismal picture of motorcycle sporting activity and its regulation as it exists in America today. Lack of leadership. Lack of focus. Lack of goals. Lack of perspective. The political structure of motorcycle sport is hardly a political structure at all, but rather a loose conglomerate of people, each pulling for his own separate bailiwick, instead of together for the sport.

It matters little whether Cooley wins, McLaughlin wins, MICUS wins or the AMA wins.

Right now, we are all losing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue