An American Rider stars abroad

DAN HUNT

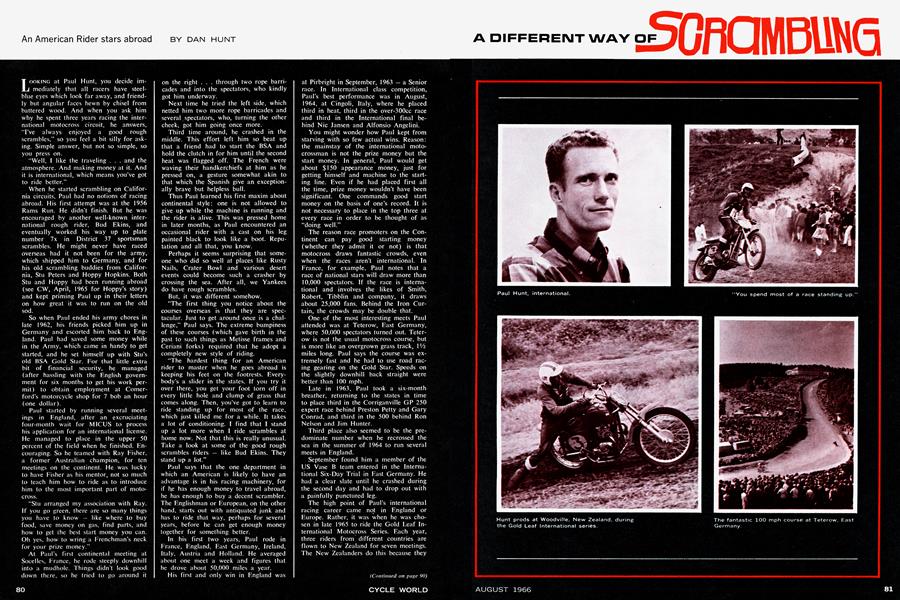

LOOKING at Paul Hunt, you decide immediately that all racers have steelblue eyes which look far away, and friendly but angular faces hewn by chisel from battered wood. And when you ask him why he spent three years racing the international motocross circuit, he answers, “I’ve always enjoyed a good rough scrambles,” so you feel a bit silly for asking. Simple answer, but not so simple, so you press on.

“Well, I like the traveling . . . and the atmosphere. And making money at it. And it is international, which means you’ve got to ride better.”

When he started scrambling on California circuits, Paul had no notions of racing abroad. His first attempt was at the 1956 Rams Run. He didn’t finish. But he was encouraged by another well-known international rough rider, Bud Ekins, and eventually worked his way up to plate number 7x in District 37 sportsman scrambles. He might never have raced overseas had it not been for the army, which shipped him to Germany, and for his old scrambling buddies from California, Stu Peters and Hoppy Hopkins. Both Stu and Hoppy had been running abroad (see CW, April, 1965 for Hoppy’s story) and kept priming Paul up in their letters on how great it was to run on the old sod.

So when Paul ended his army chores in late 1962, his friends picked him up in Germany and escorted him back to England. Paul had saved some money while in the Army, which came in handy to get started, and he set himself up with Stu’s old BSA Gold Star. For that little extra bit of financial security, he managed (after hassling with the English government for six months to get his work permit) to obtain employment at Comerford’s motorcycle shop for 7 bob an hour (one dollar).

Paul started by running several meetings in England, after an excruciating four-month wait for MICUS to process his application for an international license. He managed to place in the upper 50 percent of the field when he finished. Encouraging. So he teamed with Ray Fisher, a former Australian champion, for ten meetings on the continent. He was lucky to have Fisher as his mentor, not so much to teach him how to ride as to introduce him to the most important part of motocross.

“Stu arranged my association with Ray. If you go green, there are so many things you have to know — like where to buy food, save money on gas, find parts, and how to get the best start money you can. Oh yes, how to wring a Frenchman’s neck for your prize money.”

At Paul’s first continental meeting at Sooelles, France, he rode steeply downhill into a mudhole. Things didn't look good down there, so he tried to go around it on the right . . . through two rope barricades and into the spectators, who kindly got him underway.

Next time he tried the left side, which netted him two more rope barricades and several spectators, who, turning the other cheek, got him going once more.

Third time around, he crashed in the middle. This effort left him so beat up that a friend had to start the BSA and hold the clutch in for him until the second heat was flagged off. The French were waving their handkerchiefs at him as he pressed on, a gesture somewhat akin to that which the Spanish give an exceptionally brave but helpless bull.

Thus Paul learned his first maxim about continental style: one is not allowed to give up while the machine is running and the rider is alive. This was pressed home in later months, as Paul encountered an occasional rider with a cast on his leg painted black to look like a boot. Reputation and all that, you know.

Perhaps it seems surprising that someone who did so well at places like Rusty Nails, Crater Bowl and various desert events could become such a crasher by crossing the sea. After all, we Yankees do have rough scrambles.

But, it was different somehow.

“The first thing you notice about the courses overseas is that they are spectacular. Just to get around once is a challenge,” Paul says. The extreme bumpiness of these courses (which gave birth in the past to such things as Metisse frames and Ceriani forks) required that he adopt a completely new style of riding.

“The hardest thing for an American rider to master when he goes abroad is keeping his feet on the footrests. Everybody’s a slider in the states. If you try it over there, you get your foot torn off in every little hole and clump of grass that comes along. Then, you’ve got to learn to ride standing up for most of the race, which just killed me for a while. It takes a lot of conditioning. I find that I stand up a lot more when I ride scrambles at home now. Not that this is really unusual. Take a look at some of the good rough scrambles riders — like Bud Ekins. They stand up a lot.”

Paul says that the one department in which an American is likely to have an advantage is in his racing machinery, for if he has enough money to travel abroad, he has enough to buy a decent scrambler. The Englishman or European, on the other hand, starts out with antiquated junk and has to ride that way, perhaps for several years, before he can get enough money together for something better.

In his first two years, Paul rode in France, England, East Germany, Ireland, Italy, Austria and Holland. He averaged about one meet a week and figures that he drove about 50,000 miles a year.

His first and only win in England was at Pirbright in September, 1963 — a Senior race. In International class competition, Paul’s best performance was in August, 1964, at Cingoli, Italy, where he placed third in heat, third in the over-300cc race and third in the International final behind Nie Jansen and Alfonsio Angelini.

You might wonder how Paul kept from starving with so few actual wins. Reason: the mainstay of the international motocrossman is not the prize money but the start money. In general, Paul would get about $150 appearance money, just for getting himself and machine to the starting line. Even if he had placed first all the time, prize money wouldn’t have been significant. One commands good start money on the basis of one’s record. It is not necessary to place in the top three at every race in order to be thought of as “doing well.”

The reason race promoters on the Continent can pay good starting money (whether they admit it or not) is that motocross draws fantastic crowds, even when the races aren’t international. In France, for example, Paul notes that a race of national stars will draw more than 10,000 spectators. If the race is international and involves the likes of Smith, Robert, Tibblin and company, it draws about 25,000 fans. Behind the Iron Curtain, the crowds may be double that.

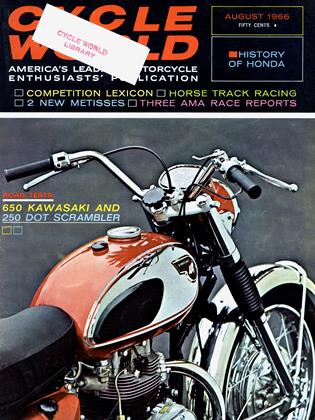

One of the most interesting meets Paul attended was at Teterow, East Germany, where 50,000 spectators turned out. Teterow is not the usual motocross course, but is more like an overgrown grass track, 1 '/2 miles long. Paul says the course was extremely fast and he had to use road racing gearing on the Gold Star. Speeds on the slightly downhill back straight were better than 100 mph.

Late in 1963, Paul took a six-month breather, returning to the states in time to place third in the Corriganville GP 250 expert race behind Preston Petty and Gary Conrad, and third in the 500 behind Ron Nelson and Jim Hunter.

Third place also seemed to be the predominate number when he recrossed the sea in the summer of 1964 to run several meets in England.

September found him a member of the US Vase B team entered in the International Six-Day Trial in East Germany. He had a clear slate until he crashed during the second day and had to drop out with a painfully punctured leg.

The high point of Paul’s international racing career came not in England or Europe. Rather, it was when he was chosen in late 1965 to ride the Gold Leaf International Motocross Series. Each year, three riders from different countries are flown to New Zealand for seven meetings. The New Zealanders do this because they believe that competition against internationals will improve their own breed, which is somewhat isolated. So Paul went in the company of two other international stars — Frank Underwood of England and Bert Lundin (brother of Sten) of Sweden.

(Continued on page 90)

A DIFFERENT WAY OF SCRaMBLING

Paul had been riding his 500cc Triumph-engined Metisse, which he’d completed in early 1965, so he was quite an object of curiosity for the natives, who lack decent machinery because of high tariffs and transport costs. All three riders were accosted with offers to buy their machinery.

As part of their tour, the three were expected to lay out an “international standard” motocross course for the second meet of the series, which took place at Christchurch. Their choice of a jump into a sandy pit horrified the native riders. Lundin, Underwood and Hunt assured them that this part of the course was very international indeed, and absolutely necessary if it was to be a “true” motocross.

When race day came, the only three riders to crash in the pit were Lundin, Underwood and Hunt.

Paul was plagued by engine trouble for most of the tour and was unable to finish three international heats. In spite of this, he placed fifth overall, tied with Underwood and New Zealander Hugh Anderson, who is better known as 125cc Grand Prix road race champion of 1965.

Paul returned home via Hawaii, stopping long enough to visit AMA rider Dick Mann and win a race on a borrowed 650cc Triumph, ahead of Mann, who had engine trouble.

His first meeting on home ground after his return was in May of this year at Irvine, California. Riding the Metisse, he won both the 500 expert and Open expert classes.

Has he returned to the states a faster rider than when he left? Most certainly, yes. But was it a direct result of riding the European circuit for three years? Paul hedges on his answer. “I’ll say that my style has improved a lot. If I said I was faster, I’d have to go out and prove it.”

He feels that, in spite of the growing American interest in international racing, there will never be many Americans trying their luck on overseas scrambles circuits. “There’s not enough rough scrambles meets here to give us proper training for abroad. Besides that, the rough scrambles over there are very different from those we do have here.”

Paul wishes that some of America’s top riders had the chance and the inclination to try the foreign circuits. “It is important that top American talent make an effort to do well abroad,” he says, adding that it is worth trying just for the experience.

“You’re representing America, in a small way, sure, but that’s what you’re doing. It’s hard to say what it feels like, but the whole thing really gets to you at the pre-race presentation. The riders line up in front of the crowd. They play the national anthem and all the flags of the countries participating are flying. It makes you feel very small.”

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

Dan Hunt

-

Special Features

Special FeaturesFrank Heacox Sells Helmets. Lots of Them. But He Opposes the Helmet Law. He Is, You See, A Motorcyclist. And We Can Thank Our Lucky Stars.

APRIL 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

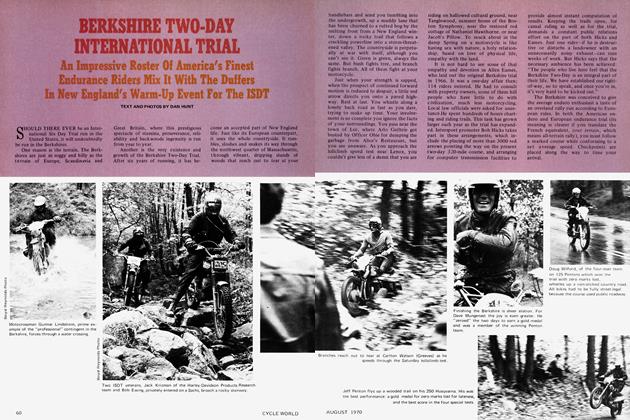

CompetitionBerkshire Two-Day International Trial

AUGUST 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureAma Racing: the Full Scam

APR 1971 By Dan Hunt