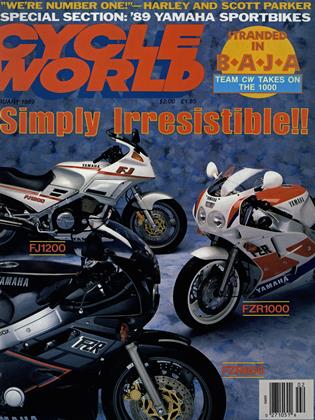

DIARY OF A DNF

QUESTION: What happens when two editors and a roadracer try Baja the easy way?

ANSWER: They discover there is no easy way

Time: 6:00 a.m. Rider: Doug Toland Section: Start to Nuevo Junction

It began with a call from David Edwards asking if I would ride for Team Cycle World in the SCORE Baja 1000. He and Ron Lawson needed a third co-rider for their Al Baker-modified Honda XR600. It didn’t take me long to say yes to racing in the most prestigious off-road race in North America.

My usual race venues are roadrace tracks, so as the Baja 1000 drew closer, some “minor” considerations came to mind. Such as being unable to spot the course markers that defined the 1000-kilometer course, and, hence, getting lost and running out of gas smack dab in the middle of nowhere.

Shortly after arriving in Ensenada, the seaside town that serves as race headquarters, I hooked up with CWs Senior Editor—and Baja guru —Ron Griewe, who took me on a pre-run of the first few miles of the course in his truck. He pointed out the course markers (orange paint sprayed on rocks, bushes and trees) and gave me first-hand advice on obstacles to watch out for. “If you see the locals waving you on, grab all the brakes you can: There’s probably a ditch or something in the road. Also, some cattle guards have ruts in front of them, so slow down there. And watch out for that rock we just ran over.”

Race day began at 3 a.m. with the Cycle World convoy barreling down the highway to reach the starting area on time. We stopped a mile outside the village of Ojos Negros. “We’ll unload the bike here and you’ll have to ride it to the start. Otherwise we’ll get caught in traffic and won’t make it to the first pit in time,” Griewe told me.“Good luck and be careful. We'll see you at Nuevo Junction.” That mile was the first time I had ever ridden an XR600.

The eerie chill I felt at the startline quickly turned to an adrenaline rush once the first bike scorched away at 6 a.m. With a bike leaving every 30 seconds, it didn’t take long for my turn to come up, and soon I found myself wideopen in top gear trying to see through the morning fog and dust kicked up by the other bikes. I couldn’t believe how much dust there was; at times I could barely see where the course went. Somehow, I managed to avoid clipping the sea of spectators that lined the first parts of the course.

After the start, I passed a few riders and was gladly out of the blinding dust, only to find myself, minutes later, in a what seemed like a Saharan sand storm. Much to my disbelief, when I reached the source of the dust, I discovered two carloads of Mexicans on the course. To top it off, a mile later I came across another carload going the wrong way. Griewe had mentioned that not all of Baja’s obstacles were natural.

As the course tightened and I tried to keep up the pace, the XR noticeably pushed its front end in hard-packed corners. One time the front end pushed right out from under me and I low-sided, knocking off the right handguard, but luckily causing no other damage. I got right back into the race, but not before a hard-ridden 250 went flying by.

After 60-plus miles of berms, ruts, sand washes and whoop-de-doos, I finally came upon a sign that read “XR's Only lA mi.” This was the first of 12 pits that AÍ Baker’s XR’s Only company had set up to service riders of its hopped-up Hondas, and I knew that my first ride was about to end. Handing the bike over to David, I briefly told him that everything was okay and patted him on the back as he took off It was 7:45 a.m. and I wasn’t scheduled to see the bike again until after dark, some 550 miles later.

Time: 7:45 a.m.

Rider: David Edwards

Section: Nuevo Junction to Borrego

I hadn’t been too worried when Griewe warned me about the “dreaded” Summit, the rocky path through the Sierra de Juarez mountains that I would encounter within miles of leaving the first pit stop. Ron leans toward overdramatization anyway, and it’s not for nothing that he’s earned the nickname “Ogre.”

But Chris Haines had me scared. Haines used to wrench for the Honda motocross team, and these days heads Baja Off-Road Tours, a company that runs expeditions through the peninsula. He’s a good rider and knows Baja (he and his teammates would eventually finish fourth in the race). When he asked me, minutes before I was to take over the XR, how many times I had pre-run the Summit, I mumbled something about the urgencies of the magazine business and told him that we hadn’t done any pre-running and that I’d never even seen the Summit before.

I seem to remember him letting out a long, low whistle before saying, “Well, good luck.” At least he had the mercy not to add, “You're going to need it.”

As it turned out, the Summit was no picnic in the park, but neither was it a ride through the fires of hell. Mainly what it was was rocky: bowling ball-sized rocks at first, grapefruit-sized at the top. As the XR crunched its way over the loose rocks, it would not only bounce up and down, but side to side, too, giving the impression of riding in an earthquake. Difficult work but not death-defying.

My only problem came on the way down, when the big XR’s engine gave a belch and stopped running. A succession of ever-weakening romps on the kickstarter left me out of breath and the bike still unstarted. In between gulps of air, I looked around me at the vast, empty landscape of Baja. Here I was in one of the world’s biggest off-road races, with 330 teams entered, and I couldn’t see a soul, not even a plume of dust off in the distance. I may as well have been on the surface of the moon, and I felt very, very lonely.

My second assault on the kickstarter was fortified with every off-color word I could think of, which must have impressed the XR, because it thundered to life after just three kicks.

After getting through the Summit, my next obstacle was a 30-mile-long sandwash. The name is deceptive, implying a smooth stretch of sand where a river once was, or will be

the next time it rains heavily. In actual fact, the name should be sand-¿222¿/-rock-¿72/¿/-bush-£2A2<7-tree-wash. This particular example was especially treacherous because its many rocks were the same color as the surrounding sand, making them all but invisible. To complicate matters, our Honda had first-generation XR’s Only suspension modifications, and wasn’t as ready for the rigors of an all-out race pace as Baker’s bikes with the latest round of fork and shock tweaks (see “Baja Commander,” p. 60). Caroming from one 60-mph run-in with a rock to the next, I felt like the pinball in some kind of diabolical arcade game, and congratulated myself for checking every option box in the Hallman catalog when I had ordered my new riding gear for the race.

The pit stop after the sandwash came as welcome relief, as the did the dry lakebed that followed, where I let the XR's 630cc engine make full use of its 100-mph gearing. Too soon, though, I was back in the rocks, this time on a fast, two-track dirt road that angled across the desert. When I spotted the Cycle World crew by the side of the course. I’d covered about 140 miles and been in the saddle for over three hours. By that time, my stamina had been drained, and every bump, jump and rock registered like a Sugar Ray Leonard punch to the kidneys. I turned the bike over to Ron, knowing that I'd have to do it all over again in three hours.

Time: 11:30 a.m.

Rider: Ron Lawson Section: Borrego to San Felipe

Maybe it’s just me, but I got the distinct impression that David was a little concerned when he handed me the motorcycle at the road crossing near Borrego. Earlier, he kept on repeating that we just needed to finish, that we weren’t in the race to win, that I should be as easy on the bike as possible.

Of course I was going to be easy on the bike. I’m always gentle with motorcycles. Even if I have suffered a mechanical dnf or two recently, they were all just bum luck and unfortunate coincidences. Just like the things that were about to happen to me. I was simply a victim of circumstance. Honest.

Shortly after getting on the bike I passed an alternate pit stop—that’s were you don’t usually stop unless you have something broken or breaking. There was supposed to be a major pit a few miles up the road where I would stop to take on fuel, so I blazed on down a whooped, sandy road. Miles went by and more miles went by. No pit. Unhappy thoughts started creeping through my mind. They became increasingly unhappy when the bike ran out of gas, and I had to fumble around for Reserve. In front of me, I could see nothing but empty desert all the way to the horizon. I rolled to a stop to consider my options. XRs are only worth about six or seven miles on Reserve. I could keep on going and quite probably run out of gas—and then slowly die in the desert and have buzzards pick my bones clean before anyone could find me. I could turn around and go backwards on the course and quite probably hit an oncoming rider or get disqualified. Or I could get off the course and try to find my way back to the alternate pit. I chose option three.

I found the pit just as I ran out of gas completely. I had lost a lot of time and places, but we were still in the race, so I wasn’t too upset. I filled up and took off. A few miles past the point where I had left the course earlier I came across another XR, out of gas: I had made the right choice. When I finally reached the official refueling pit, I told them about the stranded XR up the trail. They weren’t surprised.

My next worry came on a long section of dry lakebed. I had the throttle pegged, and it seemed like I was the only person on earth. The ground was flashing past my wheels, and the wind was pressing my goggles against my face, but it seemed as if I was barely moving at all. The horizon wasn’t getting any closer and there were absolutely no trees, bushes or landmarks for reference. I could have been on a large treadmill in a windstorm and had the same sensations. But I soon discovered I wasn’t alone. I glanced over my shoulder and saw my worst fear making a dust cloud on the distant horizon. A race buggy was catching me fast.

Now, I have no problems with going into the first turn with a dozen other riders on a motocross track. And I don’t worry too much about playing tag with other bikes in huge whoops. But the thought of dicing with a car was terrifying. As the dry lake slowly turned into a sandy, rocky sandwash, I was riding for all I was worth, trying to pull away from this nightmarish vision of ill will.

That was a mistake.

When a race buggy hits a coconut-sized rock at 50 mph, the driver might feel a slight twitch in the steering wheel. When an XR hits the same thing, it jolts into the air, the rider does a handstand, and, if he’s lucky, he slaps back on the bike like a gymnast who’s slipped and landed spreadeagle on a balance beam. After I had performed 10 or 15 of these graceless maneuvers, the buggy passed me anyway. I reduced the pace, but kept right on hitting those invisible rocks and inventing aerial moves that would make Bart Conner cringe.

After 160 miles of this, I was only too happy to give the Honda back to David. Both rims were badly bent, with some spokes missing and the rear hub cracked. The rear tire had flung off most of its center knobs, and there was even a nail sticking out, although the tire was still inflated.

Baja hadn't been very kind to me. I could only hope my next stint would be better.

Time: 2:30 p.m.

Rider: David Edwards

Section: San Felipe to Mike’s Road

When Ron herded the Honda into the pits just north of San Felipe, I didn’t know whether to shoot him or the bike: The undinged, sweet-running machine I’d given him at Borrego was now a wobbly wheeled, oil-splattered scow.

Before I knew it, though, Ron Griewe had the XR on its side and was exchanging the wheel assemblies with fresh ones that he had in the back of his truck. With the bike upright, OFs Publisher and long-time Baja fanatic, Jim Hansen, tightened bolts while Griewe’s wife Marilyn dumped a quart of oil into the Honda. Within minutes, it was race ready.

A few miles later, I wished the thing had had the good sense to die in San Felipe.

Actually, the bike was running great; it was me that was having problems. The first 20 miles of my ride paralleled the Sea of Cortez, and the course for all of those miles consisted of sandy whoop-de-doos. As far as I’m concerned, whoops—undulations in the ground that resemble a sine wave gone berserk—are The Worst Things in Dirtbiking. On a lightweight motocrosser, they can be tiring; on a top-heavy four-stroke, they suck the energy right out of a rider. Then, in the middle of slogging through these instruments of the Devil, I got zapped by an unlimited, two-seat Baja bug. One moment I was all alone, the next a Porsche-powered monster with four or five yardlong shocks per wheel came flying past about 12 inches from my left ear. I was so spooked that I immediately pulled off the course and rode through the puckerbushes all the way to the end of the whoop section. It was slower going, but it beat being turned into buggy mulch.

Unfortunately, that was not my last encounter with a four-wheeler. Several of them churned past me on a fast, dirt road, and, because we were heading directly into the setting sun, their illuminated dust blocked my forward vision as effectively as if someone had thrown a bucket of white paint at my goggles. Yet, I couldn’t slow down very much for fear of being pancaked by another truck or buggy speeding through the dust from the rear.

After 70 tense miles of whoops, buggies and fading light, I was pretty happy to see Lawson alongside the course, motioning me in for a rider change.

Time: 4:30 p.m.

Rider: Ron Lawson

Section: Mike’s Road to Johnson Ranch

The sun was slowly disappearing when David rolled into the pits at the start of the road to Mike’s Sky Ranch. I watched as the XR's Only crew installed the massive dual headlights. David looked tired, but he was in good spirits, “Just treat it like a trail ride,” he said. “Were going to finish.”

I thought so, too. Dnfs always happen in the first half of the race; we were past that point. Now I just had to deliver the bike to Doug on the other side of the peninsula, and we would cruise in for a finish in our rookie effort. Not bad for a roadracer and a couple of editors.

Wrong.

I was only on the bike for a couple of miles when I heard the sound. At first it wasn’t much, just a clacking at high rpm. I pretended I didn’t hear it. Then it got louder, eventually sounding like someone had thrown a bunch of nails into the top end. I slowed down and put the bike in a tall gear and that seemed to help, but I knew I was in trouble.

I kept on going and so did the noise. Every now and then the bike would stumble as if someone were jabbing at the rear brake. Now I faced yet another dilemma. It was dusk and I was heading directly into nowhere on a bike that could go supernova at any second. Once again, I counted my options. I could keep going (the engine clunked in response to that one), or I could get off the course and head back to the last pit (What? You quit because of a little noise?). All I knew was that I didn’t want to spend a cold night in the middle of Mexico huddled next to a broken Honda, which was most likely going to happen.

Flash!

Somewhere in the night, a camera strobe went off. Somebody was out there. I slowed the XR and began to turn around. And at that instant, the motor let out its final clunk and locked up solid. I gracelessly fell over and the bike’s headlight winked out. It was through. I was through. > Team Cycle World was through.

I leaned the bike against a fence and walked back up the dirt road. The photographer, by strange accident, was Kinney Jones, who was shooting for Cycle World. He towed me back to the pit with his aging XR350, where AÍ Baker’s crew examined the machine and signed its death certificate. A post-mortem blamed a sheared third gear for the dnf, but I know better. It was just bum luck and unfortunate coincidence.

I thought about Doug, who sat 120 miles away waiting for a bike that would never arrive.

Time: 8:40 p.m.

Rider: Doug Toland

Section: Johnson Ranch to Ensenada

I had already been at Johnson Ranch for about four hours—most of that time spent napping in my girlfriend Sandy’s car—when the leading Kawasaki zapped through at 3:10 p.m. and brought me to attention.

An hour and a half later, as the sun set over the Pacific, I was suited up and anxiously waiting for Ron and the Honda to arrive. With each four-stroke exhaust boom that approached, I rushed to the middle of the road, ready to flag Ron down. When the last of the light had eroded, I borrowed a lantern from some newfound friends who had been supplying Sandy and me with food and drink from their motorhome all afternoon. As each set of halogen headlights got closer, I held the lantern up to a piece of cardboard which had Cycle World scrawled on it, hoping to see a familiar face under the oncoming helmets. No dice.

By 7 p.m., four hours after the first bike had come by, I suspected that something was wrong, hoping that it was just mechanical and not a rider injury. Finally, at 8:40 p.m., a SCORE official came by, asking if we were waiting for bike number 687. I said yes, to which he replied, “I have a radiogram for you.” Even before I read it, I knew that I wouldn’t be riding the Team Cycle World XR into Ensenada, that the official race ledger would forever have the entry “did not finish” next to our names.

The note was succinct. It read, “Come home. We’re done.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWords From the Wise

February 1989 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCommon Threads

February 1989 By Peter Egan -

At Large

At LargeDr. Archer's Air Bag

February 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

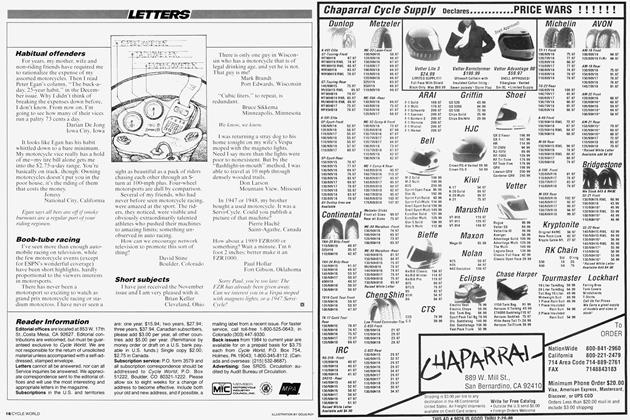

LettersLetters

February 1989 -

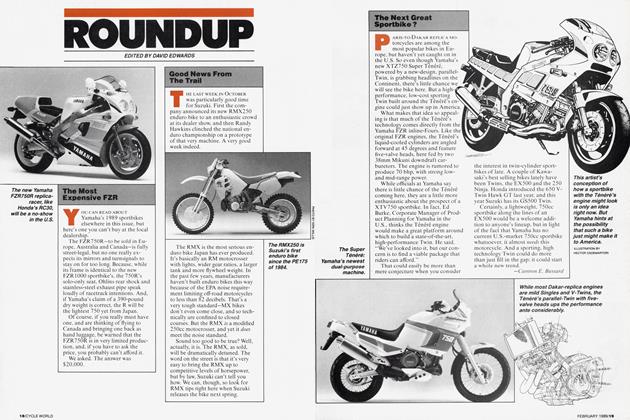

Roundup

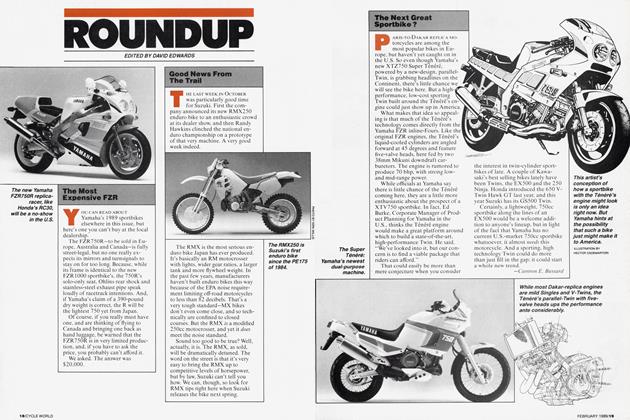

RoundupThe Most Expensive Fzr

February 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupGood News From the Trail

February 1989