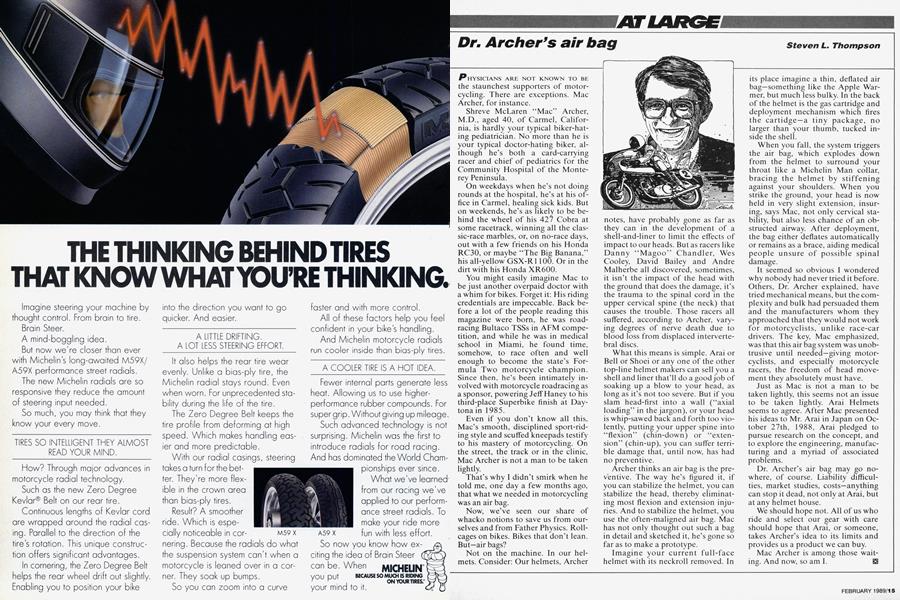

Dr. Archer’s air bag

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

PHYSICIANS ARE NOT KNOWN TO BE the staunchest supporters of motorcycling. There are exceptions. Mac Archer, for instance.

Shreve McLaren “Mac” Archer, M.D., aged 40, of Carmel, California, is hardly your typical biker-hating pediatrician. No more than he is your typical doctor-hating biker, although he’s both a card-carrying racer and chief of pediatrics for the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula.

On weekdays when he’s not doing rounds at the hospital, he’s at his office in Carmel, healing sick kids. But on weekends, he’s as likely to be behind the wheel of his 427 Cobra at some racetrack, winning all the classic-race marbles, or, on no-race days, out with a few friends on his Honda RC30, or maybe “The Big Banana,” his all-yellow GSX-R1100. Or in the dirt with his Honda XR600.

You might easily imagine Mac to be just another overpaid doctor with a whim for bikes. Forget it: His riding credentials are impeccable. Back before a lot of the people reading this magazine were born, he was roadracing Bultaco TSSs in AFM competition, and while he was in medical school in Miami, he found time, somehow, to race often and well enough to become the state’s Formula Two motorcycle champion. Since then, he’s been intimately involved with motorcycle roadracing as a sponsor, powering Jeff Haney to his third-place Superbike finish at Daytona in 1985.

Even if you don’t know all this, Mac’s smooth, disciplined sport-riding style and scuffed kneepads testify to his mastery of motorcycling. On the street, the track or in the clinic, Mac Archer is not a man to be taken lightly.

That’s why I didn’t smirk when he told me, one day a few months ago, that what we needed in motorcycling was an air bag.

Now, we’ve seen our share of whacko notions to save us from ourselves and from Father Physics. Rollcages on bikes. Bikes that don’t lean. But—air bags?

Not on the machine. In our helmets. Consider: Our helmets, Archer notes, have probably gone as far as they can in the development of a shell-and-liner to limit the effects of impact to our heads. But as racers like Danny “Magoo” Chandler, Wes Cooley, David Bailey and Andre Malherbe all discovered, sometimes, it isn’t the impact of the head with the ground that does the damage, it’s the trauma to the spinal cord in the upper cervical spine (the neck) that causes the trouble. Those racers all suffered, according to Archer, varying degrees of nerve death due to blood loss from displaced intervertebral discs.

What this means is simple. Arai or Bell or Shoei or any one of the other top-line helmet makers can sell you a shell and liner that’ll do a good job of soaking up a blow to your head, as long as it’s not too severe. But if you slam head-first into a wall (“axial loading” in the jargon), or your head is whip-sawed back and forth too violently, putting your upper spine into “flexion” (chin-down) or “extension” (chin-up), you can suffer terrible damage that, until now, has had no preventive.

Archer thinks an air bag is the preventive. The way he’s figured it, if you can stabilize the helmet, you can stabilize the head, thereby eliminating most flexion and extension injuries. And to stabilize the helmet, you use the often-maligned air bag. Mac has not only thought out such a bag in detail and sketched it, he’s gone so far as to make a prototype.

Imagine your current full-face helmet with its neckroll removed. In its place imagine a thin, deflated air bag—something like the Apple Warmer, but much less bulky. In the back of the helmet is the gas cartridge and deployment mechanism which fires the cartidge—a tiny package, no larger than your thumb, tucked inside the shell.

When you fall, the system triggers the air bag, which explodes down from the helmet to surround your throat like a Michelin Man collar, bracing the helmet by stiffening against your shoulders. When you strike the ground, your head is now held in very slight extension, insuring, says Mac, not only cervical stability, but also less chance of an obstructed airway. After deployment, the bag either deflates automatically or remains as a brace, aiding medical people unsure of possible spinal damage.

It seemed so obvious I wondered why nobody had never tried it before. Others, Dr. Archer explained, have tried mechanical means, but the complexity and bulk had persuaded them and the manufacturers whom they approached that they would not work for motorcyclists, unlike race-car drivers. The key, Mac emphasized, was that this air bag system was unobtrusive until needed—giving motorcyclists, and especially motorcycle racers, the freedom of head movement they absolutely must have.

Just as Mac is not a man to be taken lightly, this seems not an issue to be taken lightly. Arai Helmets seems to agree. After Mac presented his ideas to Mr. Arai in Japan on October 27th, 1988, Arai pledged to pursue research on the concept, and to explore the engineering, manufacturing and a myriad of associated problems.

Dr. Archer’s air bag may go nowhere, of course. Liability difficulties, market studies, costs—anything can stop it dead, not only at Arai, but at any helmet house.

We should hope not. All of us who ride and select our gear with care should hope that Arai, or someone, takes Archer’s idea to its limits and provides us a product we can buy.

Mac Archer is among those waiting. And now, so am I.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWords From the Wise

February 1989 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCommon Threads

February 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

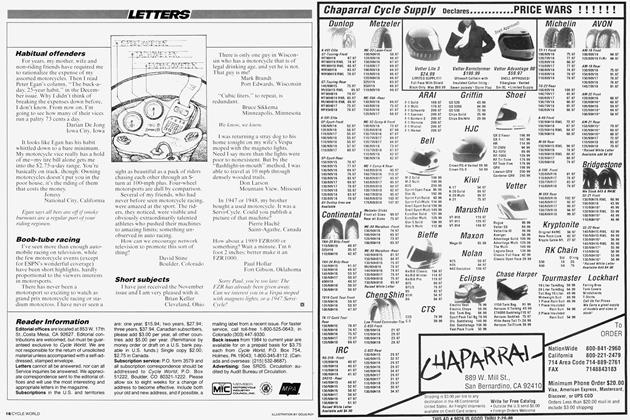

LettersLetters

February 1989 -

Roundup

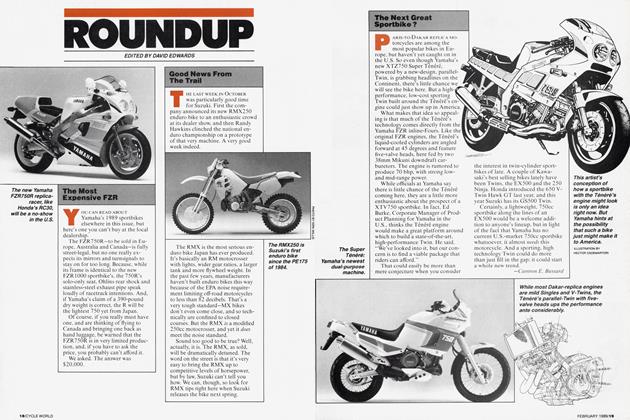

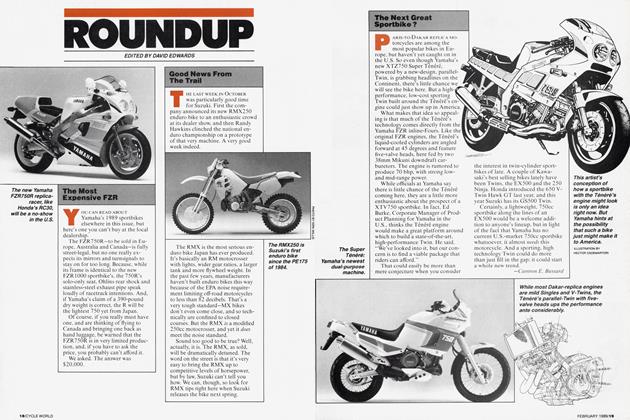

RoundupThe Most Expensive Fzr

February 1989 By David Edwards -

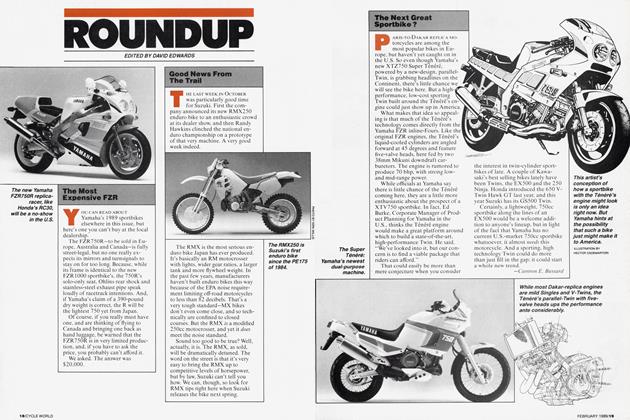

Roundup

RoundupGood News From the Trail

February 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Next Great Sportbike?

February 1989 By Camron E. Bussard