Clipboard

World Super Retread

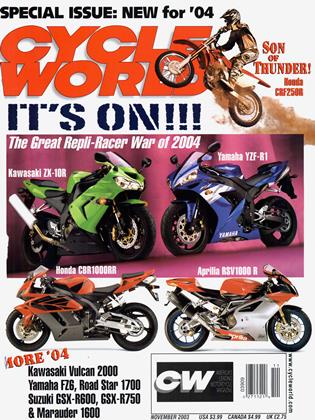

At the Laguna Seca round of World Superbike, it was announced that beginning in the 2004 season, all competitors in the series would compete on a single make of tire—a “spec tire.” Insiders correctly predicted the maker to be Pirelli. Initially, it had been rumored that a deal had been struck by which three series—World Superbike, AMA Superbike and British Superbike—would adopt a common set of technical rules. In response—again, only rumor—the manufacturers had showed renewed interest in the class—from which former participants Aprilia, Honda and Yamaha have been absent this year. Just as this hopeful news made the rounds, the spec-tire bombshell struck.

Unattractive rules proposals have been used as negotiating gambits in the past-remember the “kit rule,” which was proposed not so long ago to save manufacturers from constant heavy R&D cost?

Is the spec tire one of these?

What’s wrong with a spec tire?

By requiring all competitors to ride on a single brand, such a rule eliminates teams and riders already contracted to another tire-maker. In so doing, it also eliminates that favorite device of promoters: the wild-card rider. This is a locally rated rider from the event’s host nation who crosses swords on his home track with the world stars. With WSB already down to one-and-ahalf brands (Ducati and fractions of some others), can it afford to chop even more riders and teams from its grids?

Now the arguments in favor of a spec tire: By eliminating one of the major variables and major expenses in racing, it creates a more level playing field. Yes, the factories may go home, but in their place will spring up a much larger number of private teams (WSB events used to attract 70 entries in its mainly privateer early days).

Michelin tires are an important element in Ducati’s stunning success in MotoGR Will that tire-maker calmly accept Pirelli tires on Ducati Superbikes after years of Ducati-Michelin success in that class? Powerful relationships are at stake here, but their power to affect events has yet to be felt. Further, a spec-tire rule may not even be good for the R&D of the tire-maker chosen. Because its tires compete only with themselves, much less is learned, and at a slower pace.

Does the spec tire truly try to “create a more level playing field?” Or is it just a sanctioning body, taking over product sponsorships that have traditionally been the province of the teams? As Mr. Flammini’s FGSport has bought back WSB from Octagon, he is surely under pressure to produce income. This change may appear to him to be the shortest path to stability.

Only so much sponsorship money exists, so if more goes to the series promoter in a spec-tire deal, less remains for the teams. Clearly the gamble is that private teams, however well or poorly financed, can be transformed by FGSport and TV into world spectacle just as well as factory teams.

When one team owner complained that the spec-tire deal would cost him $350,000 in sponsorship and one of his riders $100,000, Flammini reportedly replied, “It’s for the good of the series.”

Can a series benefit from losses to its participants? Can lost participants be replaced quickly enough to keep the show going?

What next? More than one insider predicts that Michelin will move its WSB operation to the U.S., creating a tire war here and thereby making AMA Super-

bike the top production-based class worldwide. (Dunlop has been pretty much a “spec tire” in U.S. Superbike for many years.) The U.S. scene is already heavy with rider talent and teams. More lOOOcc equipment is on the way from Honda and Kawasaki. Expect some wonderful racing if this all comes to pass.

Meanwhile, AMA, FIM and British Superbike appear close to common technical rules (save for fuel and possibly throttle-body sizes). In an ideal world, this would allow riders to compete anywhere on an equal footing. The fly in this ointment is the “spec-tire barrier.”

Racing is not a democracy, nor does it necessarily represent the rule of reason. It is a business whose income must cover its expenses. If Mr. Flammini, who effectively “owns” WSB, has determined that a spec tire does the most for his bottom line, all other arguments are moot.

Racing is unpredictable, making forecasts pointless. Life doesn’t have to make sense, but we do have to cope with it. All these ingredients-new and old-fly into the pot that bubbles on history’s great stove. We’ll taste the soup next spring when World Superbike resumes under its new plan. -Kevin Cameron

KTM to field American team in Dakar

Americans practically invented desert racing and remain darned good at it. Just look at a list of winners for races like the classic Baja 1000 or the newer-to-thescene Vegas-to-Reno 500-miler. All winners are Americans.

But desert racing extends beyond the Mexican peninsula or regions of the western United States, and that would be the world’s largest sandbox: Africa. There, European off-road enthusiasts have invented their own type of desert racing >

typified by the multi-day “marathon raids” or “rally raids.”

The king of these rallies is, of course, the Dakar Rally-a multi-country race that takes nearly three weeks and covers up to 7000 miles! It’s an event that has grown to capture the imagination of adventure-loving Europeans in its 25-year history, enough to where it’s a daily staple in mainstream media news reports during the course of the race.

Curiously, it has not had much of an American presence. But that’s changing for the 26,h edition as KTM and Red Bull have announced full factory backing of a three-rider team of Americans. Team USA will challenge the Dakar-sawy Europeans in the mad dash that begins on New Year’s Day 2004 in France, ending seven countries and 18 days later in Dakar, Senegal.

For the first time in Dakar Rally history there will be a race within the race, pitting country against country. The two topplacing riders of each nation will score points toward a team championship, sort of like the Motocross des Nations, the ISDE or the Trial des Nations.

So, who are the three Americans that KTM has drafted? Two are desert veterans

with plenty of experience in overseas competition. Paul Krause and Larry Roeseler were two immediate choices of KTM North America’s Vice President of Media Relations Scot Harden, a former top desert racer and one of the few Americans to win an African rally. “Selecting Krause was a nobrainer” says Harden. “Paul had been literally calling me once a week for the last four years about doing Dakar, ever since the first-and-last time he did it in 1998.”

As for Roeseler, Harden says of the jack-of-all-trades, “L.R. and I go back over 30 years. He had mentioned to me in passing a while back that racing Dakar is something he’d like to do someday. When it looked like this thing was going to happen, I wanted to get the best off-road riders that we could to represent our country, and L.R. is the best, in my mind.”

As another possible member of the elite U.S. squad, Harden initially inquired about Civ's Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis, who finished third at the 2000 Dakar on a BMW. Lewis declined the offer.

With that door closed, KTM opted for a novel approach: an open casting call. Those who believed they had what it would

take simply needed to send Harden their resume and cross their fingers. (The third team rider was due to be chosen by the end of summer.)

Despite being armed with works 950cc Twins, team manager Harden and racers Krause and Roeseler are realistic enough to know they simply don’t have the experience to gun for the outright win. Taking the team championship and getting on the podium as individuals is, however, within their grasp.

“I’m not going there just to say I did Dakar,” Roeseler insists. “I’m going there with pretty high expectations.”

Krause echoes those sentiments and adds, “I’d love to finish on the podium. I am going there this time with an eye much more toward results than just getting to the finish. That being said, of course, you can’t be in the results if you don’t finish.” -Mark Kariya

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRoad Man

November 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoogie Music & Them Mean Old Biker Blues

November 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDodging the Dragon

November 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2003 -

Roundup

RoundupJesse James, Inc.

November 2003 By Mike Seate -

Roundup

RoundupAnti-Dive Alive!

November 2003 By Mike Keller