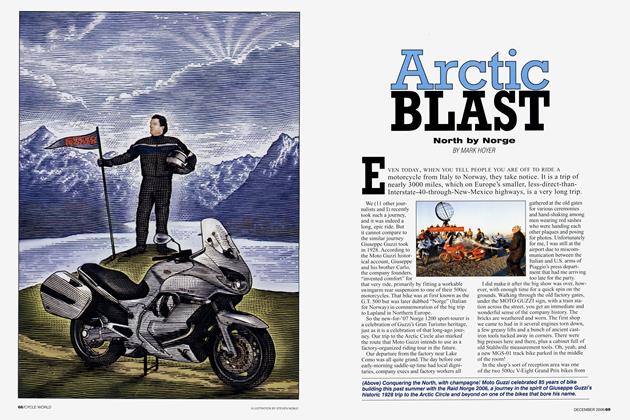

A Matter of STYLE

BRIAN CATTERSON

DREAM JOB, ISNT IT? YOU LAZE AROUND YOUR stark-white mezzanine design studio all day, whimsically sketching the motorcycles of your dreams, secure in the knowledge that your ideas will one day be transformed into metal and plastic. Your understanding boss regards you as a delicate genius and leaves you to do your work, you've got no hard deadlines, and you're confident that whatever you envision will pass muster with the legions of Ducatisti eager to embrace the Next Big Thing. Weekends, you tool around Bologna on the latest Ferrari-red prototype, drawing admiring looks from Latin lovelies.

Yeah, right.

“I don’t think I even rode a motorcycle for three years after I started here,” says Pierre Terblanche, the 45-yearold South African who since 1997 has been chief of design at Ducati, and the man behind the new 999. “I just worked all the time.”

Truth be told, Terblanche didn’t even have a proper studio at that time, just a drafting table in a big, empty room. In fact, when I visited him this past October, the paint in the new Ducati Design department was barely dry.

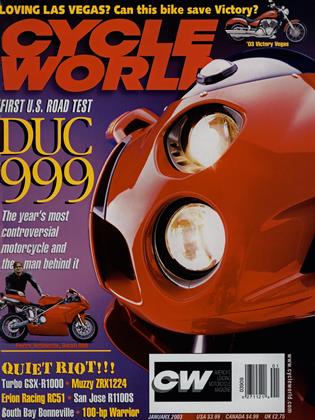

If you’ve read the letters section of this or any other motorcycle magazine lately, you know Terblanche has been lambasted for the 999’s controversial styling. Make that grilled over hot coals. Even the company website (www.ducati.com) is a minefield.

One e-mail in particular made an impression on him-and it’s not the supportive one he’s got tucked away in his wallet, either. “It read, ‘Shoot Terblanche and his dog,’” he says, unamused. “I don’t mind them criticizing me, but Pippo didn’t do anything wrong!”

A candid conversation with Pierre Terblanche, the man behind the 999

Pippo (pronounced “peepo”) is Terblanche’s sidekick, an overgrown dachshund named after a Walt Disney character, who waltzed into the Cagiva factory in Varese one day a decade ago and adopted Pierre as his new owner. They’ve been inseparable ever since-there’s a doggy bed in the comer of Terblanche’s office for when Pippo comes to work on the weekends.

Over the past few years, I’ve gotten to know Pierre-and Pippo-pretty well. In the days preceding the 999’s press introduction at the Autódromo Misano last July, we spent a day together bombing around northern Italy in his Audi A4 company car, another day kicking around the factory, and had dinner, oh, four or five times. And I learned a lot-way too much to fit in the four-page riding impression published in CVTs October, 2002, issue. So when the boss suggested I interview Terblanche for this issue, I was surprised to learn that he wanted me to return to Italy yet again. My notebook was already chock-full of information.

Well, it turns out there’s no end to what you can learn from Terblanche. The man is a walking encyclopedia of design, with a keen appreciation of form. He excitedly tells me about discovering a craftsman who restores vintage watches to their former glory, and a collection of art-deco radios is displayed on a ledge in his office. He shows me an old German book, Stromlinienform, and rifles through the pages, citing his influences-this streamlined locomotive helped shape the front of the 999’s fairing, this propeller-driven monorail inspired the muffler, this film projector led to the radiator fans, etc., etc.

Most of us can’t even draw the motorcycles parked in our driveways, let alone one that’s destined to replace Massimo Tambumi’s masterpiece, the Ducati 916, a sportbike that will go down in history as one of the most beautiful ever. Yet that doesn’t dissuade us from critiquing the 999-which surprises Terblanche not in the least.

“Designing a bike like the 999 is like standing naked center court at Wimbledon,” he acknowledges. “What do I say to the critics? Piss off until you’ve seen one in the flesh!”

When last I’d visited the factory, Terblanche’s assistants were housed in a tiny room across the hall, the walls of which were covered with photos of bikes and cars. Digging into a file drawer, Pierre pulled out a dozen or so drawings representing a small fraction of the hundreds his team produced over tens of thousands of man-hours.

“Before we even got started on the 999,1 had my guys sketch all of the existing sportbikes’ front and rear ends.. .then told them I didn’t want to see any of that ever again,” he recalls. Instead, he had them look at pictures of Formula One cars, which ultimately resulted in the 999’s smooth-sided fairing and distinctive air conveyers.

During his speech at last summer’s press introduction, Terblanche called the 999 “the first new Ducati,” based on the fact that it was the product of a proper design project, created entirely on CAD programs such as Alias, Unigraphics and Pro Engineering. The others-bikes like the current Supersports-were just styling exercises, the same old underpinnings with new skins.

“Nowadays we build a bike backwards,” he explains. “First we build it from foam core and clay, then we scan it and put it in the computer. From there, we could build a complete motorcycle using a rapid prototyping machine.” Just like the Multistrada parked across the room.

An expensive, complicated process, rapid prototyping entails a procedure called stereo lithography, in which two or more laser beams are shot into a resin bath that hardens at the points where the beams intersect to yield a three-dimensional part. Aluminum components can now be made the same way, by “synthesizing” aluminum powder. “You can do limited production runs, even crankcases,” Terblanche beams.

These prototype parts then serve as patterns for the tooling used to make the injection-molded production parts. “The theory is you spend more money initially, but only make your tooling once. Normally, we make a fiberglass mockup and paint it so everyone can look at it and be happy. But this time we went straight from clay to production.

“The software is getting to the point where you should be able to type in ‘sportbike’ and have certain parameters spring up-say, the distance between the front tire and the engine with the suspension fully compressed,” Terblanche continues. “You could in the wheelbase, steering angle, etc. and have the computer design a frame for maximum rigidity-the frame tubes have moved barely 20mm between the 851 and the 999, so we know this stuff pretty well now. The top tripleclamp and double-sided swingarm were designed this very way, by defining all the points we had to keep and connecting them.

“Having all these specs in the computer could reduce the drawing phase from 12-15 weeks down to perhaps three days, which would give me that much longer to mess about with all the other stuff. In theory, anyway...”

I asked Terblanche if they had specs from previous Ducati models-or those of rival manufacturers-filed in the computer. He shook his head and replied, “No, but we studied all that, which is how we arrived at the 999. From here, we’ll just go forward.”

But probably not as far forward as Terblanche would like. For example, while the 999 marks the first use of a CAN (Controller Area Network) line on a motorcycle, Terblanche insists that bike electronics are years behind cars, and decades behind cellular telephones. “Any engineer in Silicon Valley would find the 999’s electronics laughable,” he says.

He can envision a bike with Blue Tooth technology, a developing system utilizing radio waves that would let a motorcycle’s various electronic components “talk” to one another without any wiring at all.

The 999’s much-critiqued exhaust system, with differentdiameter pipes for each cylinder and a huge underseat muffler, also marks something of a breakthrough. “Everyone said you had to have equal-length pipes, but I asked why. Wasn’t there some other way to do it? There was, and now it’s been copied on the Desmosedici MotoGP bike.”

As proud as Terblanche is of the 999’s muffler, however, he would have been even prouder if it looked like the one his team had originally sketched, with distinctive triangular outlets. “Politics,” he says, scowling.

Another proposed part that didn’t make it into production was a beautiful cast subframe, replaced due to cost concerns by a traditional tubular piece that Terblanche says, “looks like something from a plumber’s yard.”

The clever rear suspension he designed for the 999, in which the shock attaches only to the swingarm, is another sore point-because it turned up on the Honda RC21IV MotoGP bike before the Ducati ever broke cover! “It’s not similar, it’s identical,” Terblanche proclaims, suspecting a network security problem. “And Honda patented it before we could, so we had to change ours. But it turned out all right, because we ended up improving ours even further.”

From the beginning, one of the design team’s goals was to make the 999 as compact as possible. “I saw an old Moto Guzzi 850 Le Mans and was impressed by how slim it was, with such a big motor,” Terblanche recounts. “Why did we get away from that? Why did it take 20 years to rediscover small motorcycles? You look at a 999, and compared to it an RC51 looks like an oil tanker, a GSXR a pregnant cow!”

Compact, yes, but not crowded, thanks both to a roomy riding position and an adjustable seat/tank and footpegs. That’s just the tip of the iceberg, however, because Terblanche dreams of building a bike with radically adjustable ergonomics, enabling its owner to transform it from cruiser-comfortable to superbike-serious in a matter of minutes. “But Ducati would never go for it,” he says with a shrug.

“The reality of design is that you have to fight for everything,” Terblanche adds. “I feel it’s my job to produce the bikes other companies will copy in the years to come, but others at Ducati are content to build what everyone else is building, only prettier. So you could say that with the 999, we reached all the targets they never set for us!”

If you get the idea that the 999 represents the hard-fought triumph of one man’s vision over corporate considerations, well, Terblanche would agree.

“I nearly had a nervous breakdown. That’s what it takes to do a bike like this.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Mysterious Mr. Deeley

January 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Pure Racebike

January 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIntermot Musings

January 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

January 2003 -

Roundup

RoundupMr1000: Fischer Motor Company Aims High

January 2003 By Nick Ienatsch -

Roundup

RoundupBulldog Gets More Bite

January 2003 By Matthew Miles