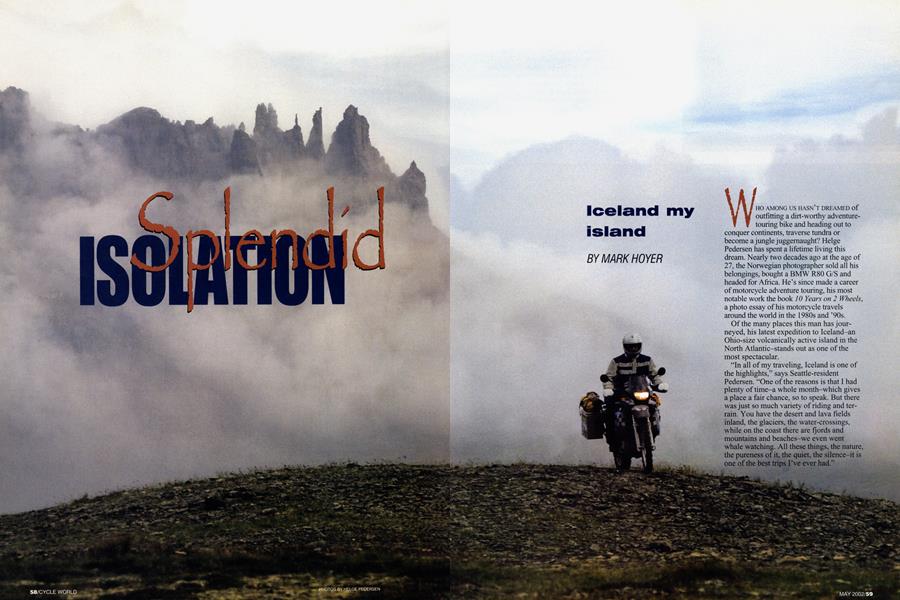

Splendid ISOLATION

Iceland my island

MARK HOYER

WHO AMONG US HASN'T DREAMED of outfitting a dirt-worthy adventure-touring bike and heading out to

conquer continents, traverse tundra or become a jungle juggemaught? Helge Pedersen has spent a lifetime living this dream. Nearly two decades ago at the age of 27, the Norwegian photographer sold all his belongings, bought a BMW R80 G/S and headed for Africa. He’s since made a career of motorcycle adventure touring, his most notable work the book 10 Years on 2 Wheels, a photo essay of his motorcycle travels around the world in the 1980s and ’90s.

Of the many places this man has journeyed, his latest expedition to Iceland-an Ohio-size volcanically active island in the North Atlantic-stands out as one of the most spectacular.

“In all of my traveling, Iceland is one of the highlights,” says Seattle-resident Pedersen. “One of the reasons is that I had plenty of time-a whole month-which gives a place a fair chance, so to speak. But there was just so much variety of riding and terrain. You have the desert and lava fields inland, the glaciers, the water-crossings, while on the coast there are íjords and mountains and beaches-we even went whale watching. All these things, the nature, the pureness of it, the quiet, the silence-it is one of the best trips I’ve ever had.”

From a guy who’s ridden through North and South America, Siberia, Mongolia, China, Singapore, Thailand, Japan, Africa, Australia and more, this is saying something.

The island at its extremes measures just 190 by 300 miles, yet Pedersen and his American riding partners-Sterling Noren, who works on cruise ships in the Caribbean, and Chris Poland, a Seattle pharmacist-covered some 3000 miles during their trip last August. Dubbed the “Globeriders Two Wheels to Iceland Expedition,” this was the first trip in a series Pedersen has planned over the next few years for a future book and video release (visit www.globeriders.com for more info).

Although Pedersen grew up in Norway, 600 miles to the east of Iceland, he knew little about the place. It wasn’t until a trusted friend returned raving about a trip there that the seed was planted. The more research Pedersen did, the more fired up he became.

He discovered that while Iceland is amazingly remoteand almost ignored by its neighbors-it features all the firstworld comforts of Europe, only with very few people. Just 278,000 residents inhabit the place, and most are located near the capital of Reykjavik in the southwest, or in small, coastal towns, where folks usually earn their living fishing.

“It’s got all the conveniences of civilization-you can get tires for your bike, you can get mechanical help and so forth,” he says. “And like one of the Icelandic bikers we met said, you're never farther away than 8-10 hours riding from the capital.”

The compact nature of Iceland was something that attracted Pedersen.

“One of the neat things is that you are limited to this kind of small island, so in a sense, you can't make a wrong turn.

I mean, it’s surrounded by water, so it’s sort of like, who

cares where you go?! Think of trying to do the same thing in Africa. If you go wrong there, you can end up in a war zone." The only weapons Pedersen and his pals were armed with were a trio of BMW F650s-two of them

newer Dakars, one an older Funduro-outfitted for the rigors of a back-country camping tour of Iceland. This included on Pedersen's bike Touratech auxiliary fuel tanks (10.3 gallons total!) and GPS, while all the bikes got aluminum saddle bags, skidplates and, most important, knobbies. "If you're going to go to Iceland you need an off-road vehicle to have fun," explains Pedersen. "You have to go to the interior of the island or to the small villages in the fjordlands on the coast, and usually you don't get to those places on good roads. I knew from my friend that you could do the island on a Gold Wing using the main roads. Maybe you'd struggle a little at some points because even these aren't all paved, but basically you could do it." Pedersen's never been one to follow the main roads, so they turned their heavily loaded F650s inland almost right away, through foggy, steep-sided, grassy valleys (there are very few trees in Iceland) and swift-flowing rivers, then straight to the heart of the island and site of Europe's largest desert. But even

with his experi ence, he and his compatriots were nonethe less concerned about what lay ahead. "You want to go to these remote places, to forge rivers and ride the tough terrain, but we all had knots in our stomachs about maybe falling over in a river and having our bikes swept away," says Pedersen. "There was a German who had that happen to him a few weeks earlier. He saved himself, but the bike was just gone." Confidence built with each success-which was good, because sometimes the river was the trail! Finally, they reached the barren, virtually unpopulated interior, where it can be days before you see another human being and the riding is tough going, but worth the effort. "We got into this lava field and it was just getting worse and worse, and more and more technical," Pedersen says of the barely marked interior track. "It's really hard work, but it's very rewarding. We could have dropped this section of the trip for something easier, but what's the point of that? Because we did this trail, we rode right up next to the Hofsjokull, the biggest glacier in Iceland, and Vatnajokull, another one nearby. You can feel the radiation of the cold from it even on the sunny day we had, and it was just incredible.

The land is black, the sky is a deep, deep blue, and then you have the white of this pair of glaciers on either side.”

One of the best things about Iceland is that it’s dotted with thermal springs, or “hot pots,” as the locals call them. With more than 100 active volcanoes, countless steam holes and geysers, clearly there’s plenty of geothermal activity to heat a little bath water.

“The hot pots were wonderful,” says Poland. “A camping group in Iceland takes care of most of them, so some have huts and cooking facilities nearby, but others were just out in the middle of nowhere. One of my favorites was one a German guy told us to go to, and gave us GPS coordinates-you’d never be able to find it on your own.”

This latter point brings to light what Pedersen thinks is one of the best new pieces of his expedition gear.

“I’m very much into GPS now,” he says enthusiastically. “It’s added a lot to traveling. With it, you can tell people exactly where to find interesting places and things.

Actually, just to have some fun at the end of the trip, we took off our front knobbies-we were switching back to street tires-and hung them on the wall in an abandoned house, took a picture and recorded the GPS coordinates. So if you’re in Iceland and you need a front tire, punch in N 65° 21.356’ W 14° 50.597’, and they’re yours-no kidding!”

GPS also had been good for some amusement earlier. Poland and Noren fell on the last day in the interior, when the rain-soaked gravel road on which they were traveling suddenly turned to slick clay.

Pedersen said it was like a "syn chronized crash." Neither rider was hurt, and after a few hours pound ing on levers, shifters and such, as well as re attaching a shorn saddlebag, they

saddlebag, they were back on the trail. Later, they met some German riders who said they had crashed in something similar.

“We both had taken GPS coordinates,” says Pedersen, “and when we compared them, it turned out it was exactly the same spot. Warning to travelers!”

The rest of the trip went smoothly, and the three ultimately circled the island, as well as making several more trips to its center. While the interior is fairly flat, the coast features much more abrupt terrain and countless waterfalls-here was some of the best riding.

“In the fjordlands, you get neat mountains and beautiful roads that seem made for motorcycling,” Pedersen relates. “They have these serpentine curves going up and down the mountains and around the fjords. One of the amazing things is that the other side of a fjord could be spitting-distance away, but it could take you an hour to ride there on land! Here, mostly the road varied between good asphalt and good dirt. There were some potholes and things, but we had a lot of fun.”

Pedersen says no Icelandic vacation is complete without visiting the former herring capi-

tal of the world, Siglufjordur, population 1065. It is “former” because one season after decades of good harvests, the herring just didn’t return. It’s a quiet place now, one where they rented an entire four-story hotel for $ 150 a night. Of course, then they headed to the local video shop/mini-mart where a sixpack of beer cost $35!

“We were glad to pay it!” Poland laughs.

Pedersen says a month in Iceland still wasn’t long enough, but the best riding season is August, which they had used up. At the end of the trip, one of the tents blew over (occupant still inside!) and so did a bike. Winter was coming, and even though the warm ocean current of the

Gulf Stream keeps Iceland fairly mild for such a northerly place (summer highs can be in the 40s and 50s), it was time to leave.

Surprised and delighted by this sort of secret jewel of the North Atlantic,

Pedersen is glad to have Iceland stamped in his passport.

“The wonderful thing about it is that you are very intimate with everything, but at the same time you feel like you’re on another planet. You’re not in Europe, and you really can’t place yourself. It gives you a weird feeling, even with all the other places I’ve been.”

We’ll have to see what he thinks after his upcoming trip to Madagascar. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

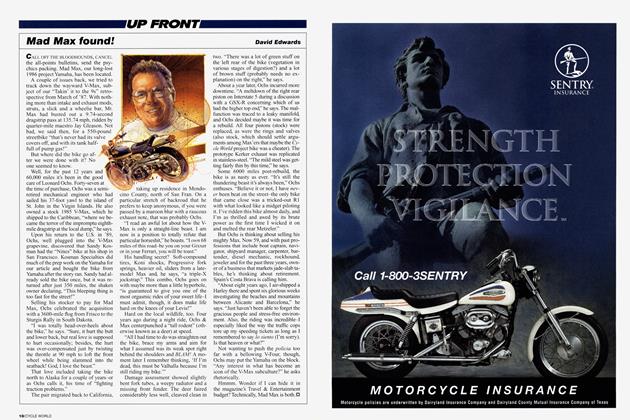

Up FrontMad Max Found!

May 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the Barber

May 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRoom At the Top

May 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the V-Rod: Harley's Next Revolution?

May 2002 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedici!

May 2002 By Brian Catterson