Very First Vee

Before aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss took to the air, he showed Harley and Indian how it was done

ALLAN GIRDLER

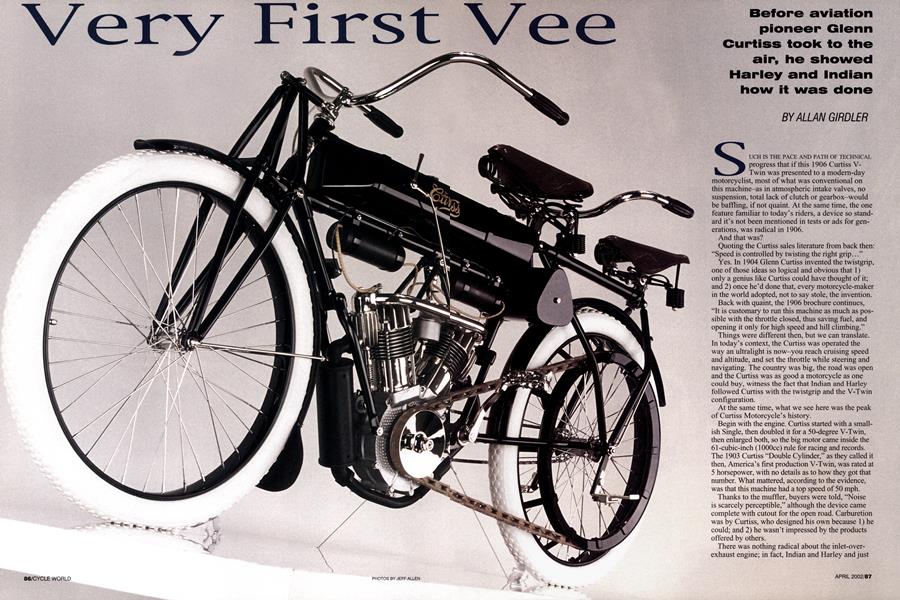

SUCH IS THE PACE AND PATH OF TECHNICAL progress that if this 1906 Curtiss V-Twin was presented to a modern-day motorcyclist, most of what was conventional on this machine-as in atmospheric intake valves, no suspension, total lack of clutch or gearbox-would be baffling, if not quaint. At the same time, the one feature familiar to today’s riders, a device so standard it’s not been mentioned in tests or ads for generations, was radical in 1906.

And that was?

Quoting the Curtiss sales literature from back then: “Speed is controlled by twisting the right grip...”

Yes. In 1904 Glenn Curtiss invented the twistgrip, one of those ideas so logical and obvious that 1) only a genius like Curtiss could have thought of it; and 2) once he’d done that, every motorcycle-maker in the world adopted, not to say stole, the invention.

Back with quaint, the 1906 brochure continues, “It is customary to run this machine as much as possible with the throttle closed, thus saving fuel, and opening it only for high speed and hill climbing.”

Things were different then, but we can translate. In today’s context, the Curtiss was operated the way an ultralight is now-you reach cruising speed and altitude, and set the throttle while steering and navigating. The country was big, the road was open and the Curtiss was as good a motorcycle as one could buy, witness the fact that Indian and Harley followed Curtiss with the twistgrip and the V-Twin configuration.

At the same time, what we see here was the peak of Curtiss Motorcycle’s history.

Begin with the engine. Curtiss started with a smallish Single, then doubled it for a 50-degree V-Twin, then enlarged both, so the big motor came inside the 61-cubic-inch (lOOOcc) rule for racing and records. The 1903 Curtiss “Double Cylinder,” as they called it then, America’s first production V-Twin, was rated at 5 horsepower, with no details as to how they got that number. What mattered, according to the evidence, was that this machine had a top speed of 50 mph.

Thanks to the muffler, buyers were told, “Noise is scarcely perceptible,” although the device came complete with cutout for the open road. Carburetion was by Curtiss, who designed his own because 1) he could; and 2) he wasn’t impressed by the products offered by others.

There was nothing radical about the inlet-overexhaust engine; in fact, Indian and Harley and just about everyone in the business used pocket valves, as seen on the DeDion-Bouton engines that pioneered motorcycling.

Curtiss offered engineering, though, with large flywheels and refined cast iron, and roller bearings where lesser motorcycles used bushings. The intake valves could be depressed to allow injection of gas on those cold mornings, and the central camshaft allowed both exhaust valves to be opened for starting with one lever.

Drive was as simple and foolproof as Curtiss could make it. Direct is the word here, with a flat leather belt and a leather-covered pulley on early models. Couldn’t be easier: Lift the exhaust valves, set the controls, pedal until the engine is whirring away, drop the valves and the engine takes over. Even the gearing was simplified. Standard roadwear was a 20-inch rear pulley and 5-inch front, or 4:1, with optional fronts in 4-, 5.75or 7-inch diameters.

The brochure mentions the use of high-grade steel for the frame and fork, adding that no Curtiss had ever suffered structural failure of these componentsone assumes this is a subtle hint that other, lesser makes couldn’t make that claim.

The standard 1906 model, as shown here, was, well, pretty standard. Rims were 28 inches in diameter with 2.5-inch-wide tires, and virtually the only option was the passenger accommodation. There was a competition model, lower and shorter and priced at $300, against $275 for the road machine, but the pamphlet warned that the racer was “not recommended for road work, as it lacks the easy riding qualities found in the long wheelbase and large tires” of the standard model.

That last claim puts us into the realm of relativity: A long wheelbase and big tires may, in fact, deliver a better ride than a short chassis on inflexible tires, but even so, they don’t equal suspension.

Rival makers had been experimenting with suspension, front and rear, since 1903. Real, effective bump-absorption would be delayed for another 30 to 50 years, but everyone knew that suspension was worthwhile. Curtiss seems to have been the exception. The ’06 model was the peak of the brand, collectors now agree, because this model had features-especially the twistgrip-that the other makes were copying. But when Harley-Davidson introduced the elegantly named Step Starter, Indian went to gear primary and chain final drive, and Cyclone had a triangulated swingarm, Curtiss kept the belt and the pedals.

Oh, there were some concessions to progress. While the drive belt stayed, in ’06 it became V-shaped for better grip.

and Curtiss proclaimed its superiority until the brand ceased in 1910-today, Harley-Davidson and Victory would agree. And history tells us that late in the make’s life the Curtiss could be bought with front suspension, a quarter-elliptic spring rather like the one seen on Indians of the time, speaking of ideas too good not to borrow. Then there was the oddly elegant WThree motor, none of which, sadly, seems to have survived.

Not a lot of detail development, though, for a man who would go on to claim more than 500 inventions in his relatively short lifetime. Educated guesswork says first, that Curtiss must have believed he’d taken the motorcycle as far as it needed to go-that is, pedal ’til the engine fires, sit loosely and get home before dark was enough. Second, he’d lost interest in bumping along on the ground when he could be soaring through the air, so that’s where his passions had, urn, flown.

Meanwhile, this particular example is a typical survivor. What it did was survive.

Owner Otis Chandler, who loaned this machine from his museum in Oxnard, California, to the Guggenheim display in Las Vegas, says the motorcycle was acquired from a collector who’d had it in the back of his bam for years. He, in turn, got it from another collector who'd had it for years. It had been saved from neglect, but not preserved.

Restorer and now classics dealer Glenn Bator (www.batorinternational.com), who tackled the project for Chandler, says it was one of the more challenging resurrections he’s undertaken. Just being parked in the comer is hard on motorcycles, and this restoration involved tasks as major as replacing part of the frame, never mind the missing little parts and the search for just the right paint and plating.

“The Curtiss was one of the most tedious and time-consuming jobs I’ve put out in all my years of restoration work, but I fell in love with this bike the first time I saw it,” says Bator. “I feel honored to bring it back to life; it was a real heart-and-soul project.” So, too, for Chandler, who had the resources and the will to do things right, even when a restoration is more accurately described as a re-creation.

On that note, Chandler and Bator cheerfully concede that although their research says this is a 1906 model, if some details emerge-the pitch of a bolt, the size of a fastener, something like that-proving it’s an ’07, the placard would be changed without a struggle. A 1906 or ’07 Curtiss Double Cylinder are that close.

Looking at it now, almost a full century later, makes one wonder: What would Curtiss the bike have been if Curtiss the man hadn’t lost interest? E3

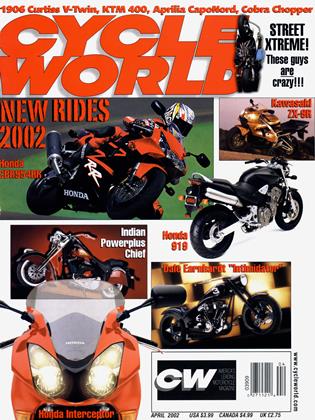

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter of the Month

April 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Mouse That Roared

April 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Rpm Chronicles

April 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Bmw Über-Tourer Twin

April 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUltimate Towing Machine?

April 2002 By David Edwards