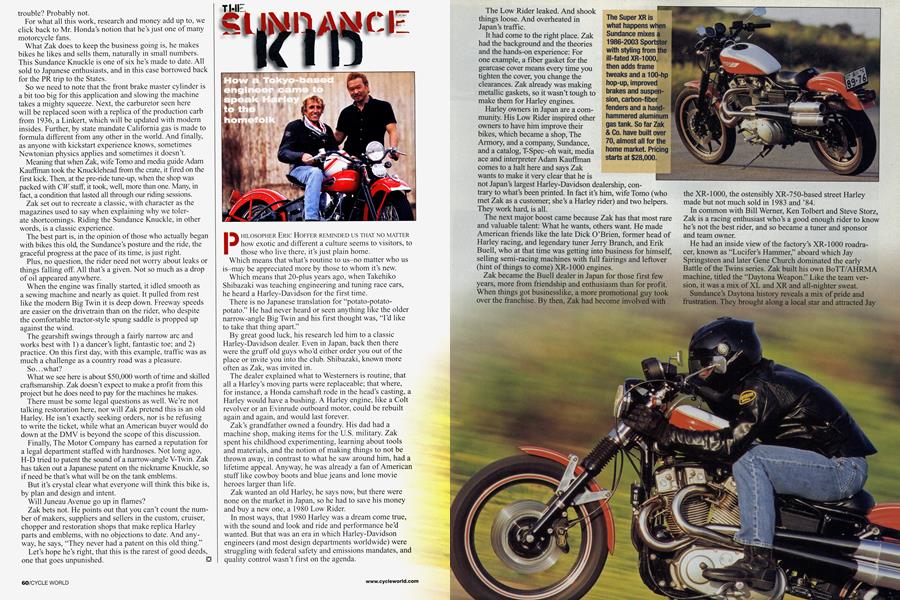

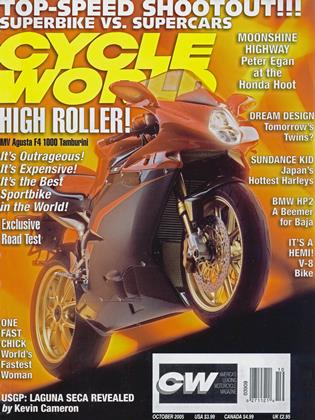

THE SUNDANCE KID

How a Tokyo-based engineer came to speak Harley to the homefolk

PHILOSOPHER ERIC HOFFER REMINDED US THAT NO MATTER how exotic and different a culture seems to visitors, to those who live there, it's just plain home.

Which means that what’s routine to us-no matter who us is-may be appreciated more by those to whom it’s new.

Which means that 20-plus years ago, when Takehiko Shibazaki was teaching engineering and tuning race cars, he heard a Harley-Davidson for the first time.

There is no Japanese translation for “potato-potatopotato.” He had never heard or seen anything like the older narrow-angle Big Twin and his first thought was, “I’d like to take that thing apart.”

By great good luck, his research led him to a classic Harley-Davidson dealer. Even in Japan, back then there were the gruff old guys who’d either order you out of the place or invite you into the club. Shibazaki, known more often as Zak, was invited in.

The dealer explained what to Westerners is routine, that all a Harley’s moving parts were replaceable; that where, for instance, a Honda camshaft rode in the head’s casting, a Harley would have a bushing. A Harley engine, like a Colt revolver or an Evinrude outboard motor, could be rebuilt again and again, and would last forever.

Zak’s grandfather owned a foundry. His dad had a machine shop, making items for the U.S. military. Zak spent his childhood experimenting, learning about tools and materials, and the notion of making things to not be thrown away, in contrast to what he saw around him, had a lifetime appeal. Anyway, he was already a fan of American stuff like cowboy boots and blue jeans and lone movie heroes larger than life.

Zak wanted an old Harley, he says now, but there were none on the market in Japan, so he had to save his money and buy a new one, a 1980 Low Rider.

In most ways, that 1980 Harley was a dream come true, with the sound and look and ride and performance he’d wanted. But that was an era in which Harley-Davidson engineers (and most design departments worldwide) were struggling with federal safety and emissions mandates, and quality control wasn’t first on the agenda.

The Low Rider leaked. And shook things loose. And overheated in Japan’s traffic.

It had come to the right place. Zak had the background and the theories and the hands-on experience: For one example, a fiber gasket for the gearcase cover means every time you tighten the cover, you change the clearances. Zak already was making metallic gaskets, so it wasn’t tough to make them for Harley engines.

Harley owners in Japan are a community. His Low Rider inspired other owners to have him improve their bikes, which became a shop, The Armory, and a company, Sundance, and a catalog, T-Spec-oh wait, media ace and interpreter Adam Kauffman comes to a halt here and says Zak wants to make it very clear that he is very not Japan’s largest Harley-Davidson dealership, con trary to what’s been printed. In fact it’s him, wife Tomo (who met Zak as a customer; she’s a Harley rider) and two helpers. They work hard, is all.

The next major boost came because Zak has that most rare and valuable talent: What he wants, others want. He made American friends like the late Dick O’Brien, former head of Harley racing, and legendary tuner Jerry Branch, and Erik Buell, who at that time was getting into business for himself, selling semi-racing machines with full fairings and leftover (hint of things to come) XR-1000 engines.

Zak became the Buell dealer in Japan for those first few years, more from friendship and enthusiasm than for profit. When things got businesslike, a more promotional guy took over the franchise. By then, Zak had become involved with the XR-1000, the ostensibly XR-750-based street Harley made but not much sold in 1983 and ’84.

In common with Bill Werner, Ken Tolbert and Steve Storz, Zak is a racing enthusiast who’s a good enough rider to know he’s not the best rider, and so became a tuner and sponsor and team owner.

He had an inside view of the factory’s XR-1000 roadracer, known as “Lucifer’s Hammer,” aboard which Jay Springsteen and later Gene Church dominated the early Battle of the Twins series. Zak built his own BoTT/AHRMA machine, titled the “Daytona Weapon.” Like the team version, it was a mix of XL and XR and all-nighter sweat.

Sundance’s Daytona history reveals a mix of pride and frustration. They brought along a local star and attracted Jay Springsteen, no less, to fly the flag. They set lap records, and won preliminary races. They got help from O'Brien and got to use the insider’s shop, Robinson’s H-D, close to the track. They also suffered a series of trifling flaws, mostly from outside suppliers. The battery went dead one year, followed by a flexing flywheel that cramped the oil pump drive. A front tire went flat, a bolt fell out of the countershaft retainer.

And so it’s gone at Daytona Beach. The scrapbook has a photo of the Weapon next to the legendary Britten. That was the year Sundance won a BoTT class.

"You beat the Britten?!"

Zak smiles ruefully. No, it turns out. The Britten won, with the Japanese Pro fourth on the Weapon and Jay sixth on a street version of the Sundance racer.

As a character indicator, not only does Zak bear no grudge, he was a Britten fan. There was one of the rare machines in Japan and Zak went to the Honda museum to suggest they buy it. The suggestion was rejected, quickly and stiffly, leading Zak to wisecrack that if Mr. Honda came back now, he’d never get a job with Honda Motors.

More to the point here, Zak began working on HarleyDavidsons before cable TV turned motorcycles, specifically pseudo-choppers, into show biz. Not his thing. Zak knows the builders in the U.S. and Japan who construct these things. He’s careful to say he respects them and the creations they display, but in his own case, his interests are technology and sport, pretty much in balance, and the television fad has no appeal for him.

(Pause for purists to nod approval.)

The sport aspect began with those XR-1000 engines used by Buell. Zak bought an XR-1000 and as with the Low Rider, he liked most of it, and reckoned he could fix the other parts. He became the man to see in Japan if you had an XR-1000. More of a hobby, he says, ’cause the sales there were only a fraction of the sales in America and those were a disaster.

Since then, as seen on the previous page, Sundance has corrected the XR’s flaws, artistic as well as technical, and has moved ahead.

At 46, Zak has spent exactly half his life working on and improving Harley-Davidsons. It’s exquisite work...make that art. He doesn’t produce a lot of bikes and parts, they are expensive and they’re not for everybody.

Again, Zak stops Kauffman in mid-translation: “He wants to make sure you know that this is not profit.”

“This is passion,” Zak says. Point made

Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontProject 100 Down

October 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMad Dogs And Irishmen

October 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSausages And Steel

October 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2005 -

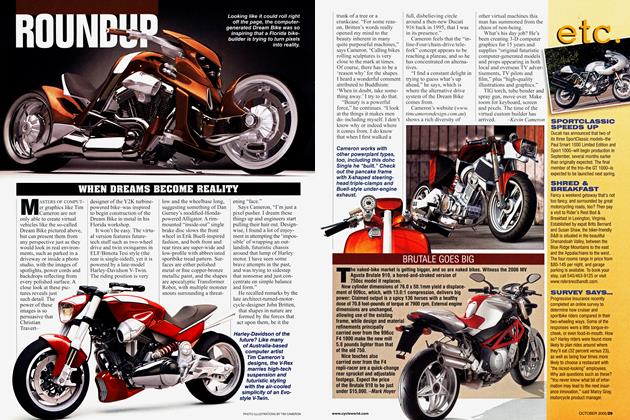

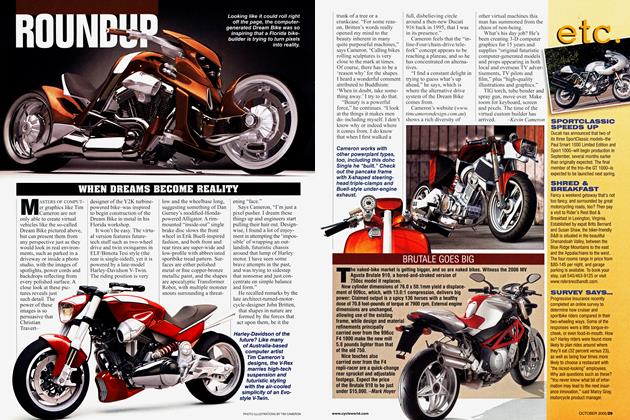

Roundup

RoundupWhen Dreams Become Reality

October 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBrutale Goes Big

October 2005 By Mark Hoyer