CYCLE WORLD TEST

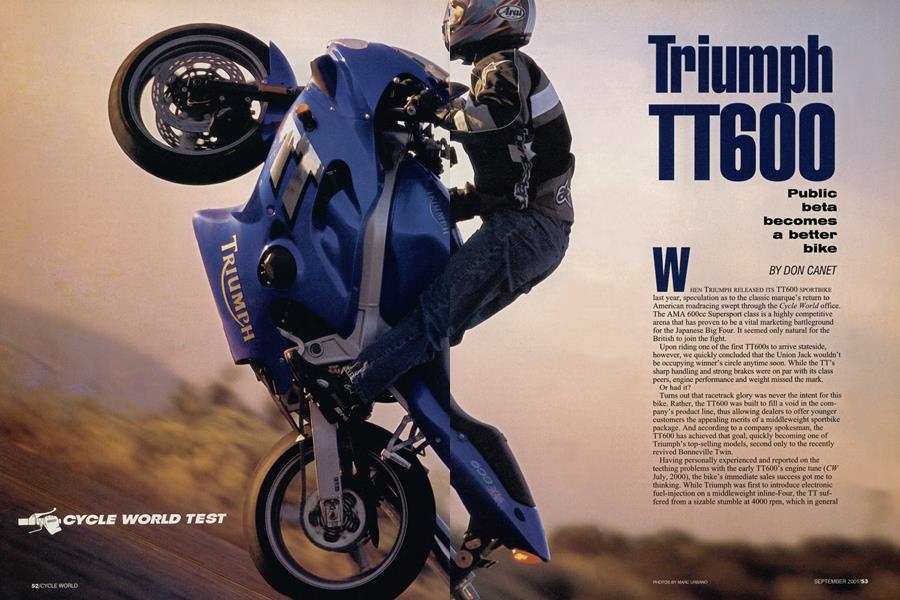

Triumph TT600

Public beta becomes a better bikez

DON CANET

WHEN TRIUMPH RELEASED ITS TT600 SPORTBIKE last year, speculation as to the classic marque’s return to American roadracing swept through the Cycle World office. The AMA 600cc Supersport class is a highly competitive arena that has proven to be a vital marketing battleground for the Japanese Big Four. It seemed only natural for the British to join the fight.

Upon riding one of the first TT600s to arrive stateside, however, we quickly concluded that the Union Jack wouldn’t be occupying winner’s circle anytime soon. While the TT’s sharp handling and strong brakes were on par with its class peers, engine performance and weight missed the mark.

Or had it?

Turns out that racetrack glory was never the intent for this bike. Rather, the TT600 was built to fill a void in the company’s product line, thus allowing dealers to offer younger customers the appealing merits of a middleweight sportbike package. And according to a company spokesman, the TT600 has achieved that goal, quickly becoming one of Triumph’s top-selling models, second only to the recently revived Bonneville Twin.

Having personally experienced and reported on the teething problems with the early TT600’s engine tune (CW July, 2000), the bike’s immediate sales success got me to thinking. While Triumph was first to introduce electronic fuel-injection on a middleweight inline-Four, the TT suffered from a sizable stumble at 4000 rpm, which in general street use seriously hampered the bike’s rideability. This glitch could have been a death sentence for a bike intended for everyday transportation, but thanks to the marvel of modem electronics, dealers were able to upgrade customers’ injection maps as new ones became available-and moreover, did so free of charge.

Software updates are commonplace in today’s data-sawy society. One would have to imagine that the TT600’s target audience-riders in their midto late-20s-is a computer-literate lot. Most being home-computer users, they’ve no doubt purchased a PC application or game only to find an update (or several) were needed to eliminate bugs that escaped the product’s beta testing.

I spoke with one TT600 owner who said he’d purchased his bike when it first came out, and had immediately installed the accessory performance exhaust canister and remapped the injection to dodge the engine stumble. Dealers report that the less restrictive, albeit louder, canister has indeed been a popular item.

So now, one year down the road, we have a current TT600 testbike in-house. Specifications are unchanged from last year’s model with the exception of the latest engine-tune data uploaded into the engine-management system’s brain. While there’s still a trace of power flux below 4000 rpm, throttle response and quality of low-rev output are leaps and bounds better than before. This improvement has not come without a cost, however, as our dyno showed a 3 horsepower loss throughout the midrange and top end. Triumph has confirmed our findings to be consistent with its own results. Believe me, though, if this is the price for the low-rev remedy, then it was well worth it. Furthermore, the finicky cold-start manners that plagued our previous testbike also have been fixed. Simply thumb the starter button without applying any throttle and the engine fires to life, settling into a high idle for a few minutes as it warms.

My first ride around town revealed a bothersome amount of drivetrain lash and sloppy upshifts. Adjusting the throttle cable to remove excess slack helped a good deal. While gear changes from first to second remain clunky, action in the upper gears is very smooth. Keeping the throttle slightly cracked open when shifting produces the best results. We had complained of a grabby clutch with our 2000 TT, but this 2001 bike provided smooth engagement, though it still has a fairly stiff pull compared to that of other 600s.

At slower in-town speeds, the TT’s liquid-cooled inline four-cylinder engine is audibly buzzy, emitting a sound reminiscent of a playing card ticking in the spokes of a kid’s bicycle, another good excuse for mounting the accessory canister with its pleasing exhaust note. Engine vibration is felt through the bars, pegs and tank, with vibes smoothing somewhat between 5000 and 6000 rpm (60-70 mph in sixth gear) and another smooth band at 7000 rpm, which is good for about 80 mph in top gear. The mild vibration level while cruising in this sweet spot, combined with a moderately sporting riding position atop a wellpadded saddle, makes the TT an enjoyable freeway mount. While taller riders may find the pegs a bit high, leaving too little legroom for long-range comfort, my 5-foot-10 frame found the TT a set of soft saddlebags away from legitimate sport-touring duty.

Venture into a set of curves and the TT600 really shines. Rolling on grippy Bridgestone BT010 radiais, the chassis steers light and neutral. Feedback through the fully adjustable KYB suspension is excellent, while striking a good balance between bump absorption and chassis control. Cornering clearance is on par with the best 600s, so skimming the pegs takes some doing. Stability remains solid over rough surfaces or at high speed, a real credit to a bike that feels so light on its feet.

Another area where Triumph sportbikes have gained widespread praise is the brakes.

The TT’s Nissin four-pot front calipers don’t disappoint, providing strength and consistency without being overly sensitive in normal street use. The rear setup also provides very good feel and function when used in conjunction with the front.

Dragstrip testing backed up our dyno results with a best pass of 11.42 seconds at 121 mph-slightly off the 11.26-second/122-mph showing of last year’s bike. If this seems like a step backwards, just consider the amount of time spent below 7000 rpm, an area in which the current bike has been vastly improved. That said, those caught up in the acceleration and power-figure wars will probably want to look into the Big Four’s 600cc offerings.

At $8299, the TT600 remains the most expensive of mainstream middleweight sportbikes. Based strictly on perform-

ance and function, the class offers better bikes for less money. But for some, owning a machine with a made-inEngland difference is worth the added premium; it’s the gentleman’s choice. And you’ll never be accused of being just another Kurds Roberts wannabe.

EDITORS' NOTES

BACK IN THE EARLY 1980S, WHEN 1 FIRST took notice of streetbikes, my focus was on current offerings, and Triumph was history. Coming along well after the Golden Era of Britbike prosperity has relieved me of feeling any nostalgic emotions when riding the revived company’s latest products.

Call me heartless, then, but I view the TT600 as a piece of hardware to be judged purely on function. And, as such, I find no reason to recommend this bike over the Honda CBR600F4Í, CWs recent pick for Best Middleweight Streetbike of 2001. While these two 600s share parallel missions-that of being balanced-yet-sporty everyday rides-the Honda simply does it all better while costing less.

If the TT were a clear-cut bargain, perhaps I could be swayed. I do understand, however, that for many, the Triumph name alone makes it worth paying a premium.

-Don Canet, Road Test Editor

AFTER AN EXCRUCIATINGLY LONG LAYOFF due to a broken wrist, I’ve been getting back up to speed on one of my favorite sportbikes, Honda’s VTR1000F Super Hawk. Though unchanged since its 1997 debut, the half-faired V-Twin remains a faultless handler, with friendly ergonomics, good vibrations and terrific Open-class grunt.

Which is why I kept putting off plans to ride our ’01 TT600, in spite of its beautiful Caspian Blue paint and redone fuel-injection mapping. After all, the VTR is smoother, more comfy, more powerful and scales-in only 25 pounds heavier. Then there’s the price issue: As Road Test Editor Canet points out, the Triumph costs a class-topping $8299. The bigger-bore Honda, meanwhile, rings in at $8999, a $700 premium that I would gladly pay. (And dealers are dealin’, have been for years.) Apples and oranges? I think not. Out in the real world, where most folks don’t have a dozen bikes from which to choose, these are important, potentially deal-breaking issues. Maybe if the Triumph were a 750... -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

I’VE NEVER UNDERSTOOD TRIUMPH’S decision to produce a 600cc Four rather than one of its trademark Triples. The company line is that computer simulations determined engineers couldn’t get competitive power from three cylinders. Well, news flash, they didn’t get competitive power from four cylinders, either!

The fact that the TT600 can’t compete with the latest Japanese middleweights might be excusable if it exuded traditional European mechanical character, but it doesn’t. In fact, its blandness rivals that of the most appliance-like Japanese machine.

I can’t help thinking Triumph should have taken a page from Ducati’s book and built a 750cc version of its existing Open-class Superbike, the 955i Daytona. That way, they’d have performance and character. Sell it for the same price as the TT600 and it would come off as an inexpensive alternative to a 748, rather than an overpriced Katana.

It’s not too late. -Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

TRIUMP TT600

$8299

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpanish Flyers

September 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAncient Beemer Update

September 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTurning

September 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Unleashes Bulldog V-Twin!

September 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupNew Life For A Legend

September 2001 By Matthew Miles