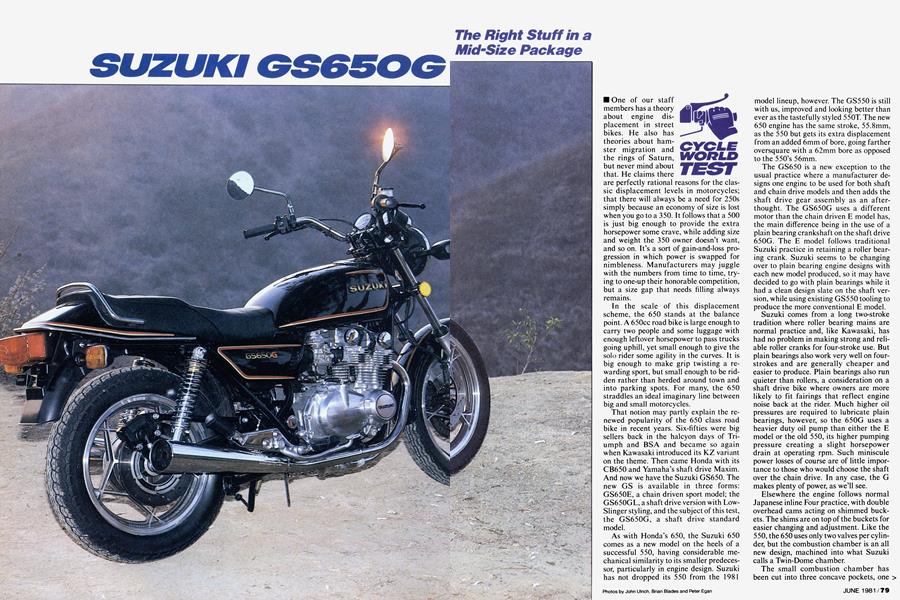

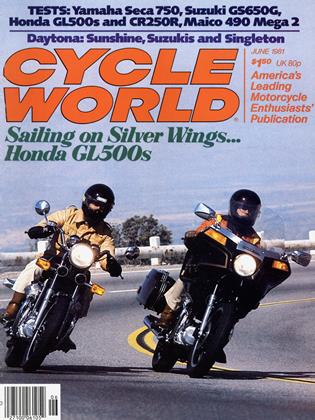

SUZUKI GS65OG

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Right Stuff in a Mid-Size Package

One of our staff members has a theory about engine displacement in street bikes. He also has theories about hamster migration and the rings of Saturn, but never mind about that. He claims there are perfectly rational reasons for the classic displacement levels in motorcycles; that there will always be a need for 250s simply because an economy of size is lost when you go to a 350. It follows that a 500 is just big enough to provide the extra horsepower some crave, while adding size and weight the 350 owner doesn’t want, and so on. It’s a sort of gain-and-loss progression in which power is swapped for nimbleness. Manufacturers may juggle with the numbers from time to time, trying to one-up their honorable competition, but a size gap that needs filling always remains.

In the scale of this displacement scheme, the 650 stands at the balance point. A 650cc road bike is large enough to carry two people and some luggage with enough leftover horsepower to pass trucks going uphill, yet small enough to give the solo rider some agility in the curves. It is big enough to make grip twisting a rewarding sport, but small enough to be ridden rather than herded around town and into parking spots. For many, the 650 straddles an ideal imaginary line between big and small motorcycles.

That notion may partly explain the renewed popularity of the 650 class road bike in recent years. Six-fifties were big sellers back in the halcyon days of Triumph and BSA and became so again when Kawasaki introduced its KZ variant on the theme. Then came Honda with its CB650 and Yamaha’s shaft drive Maxim. And now we have the Suzuki GS650. The new GS is available in three forms: GS650E, a chain driven sport model; the GS650GL, a shaft drive version with LowSlinger styling, and the subject of this test, the GS650G, a shaft drive standard model.

As with Honda’s 650, the Suzuki 650 comes as a new model on the heels of a successful 550, having considerable mechanical similarity to its smaller predecessor, particularly in engine design. Suzuki has not dropped its 550 from the 1981 model lineup, however. The GS550 is still with us, improved and looking better than ever as the tastefully styled 550T. The new 650 engine has the same stroke, 55.8mm, as the 550 but gets its extra displacement from an added 6mm of bore, going farther oversquare with a 62mm bore as opposed to the 550’s 56mm.

The GS650 is a new exception to the usual practice where a manufacturer designs one engine to be used for both shaft and chain drive models and then adds the shaft drive gear assembly as an afterthought. The GS650G uses a different motor than the chain driven E model has, the main difference being in the use of a plain bearing crankshaft on the shaft drive 650G. The E model follows traditional Suzuki practice in retaining a roller bearing crank. Suzuki seems to be changing over to plain bearing engine designs with each new model produced, so it may have decided to go with plain bearings while it had a clean design slate on the shaft version, while using existing GS550 tooling to produce the more conventional E model.

Suzuki comes from a long two-stroke tradition where roller bearing mains are normal practice and, like Kawasaki, has had no problem in making strong and reliable roller cranks for four-stroke use. But plain bearings also work very well on fourstrokes and are generally cheaper and easier to produce. Plain bearings also run quieter than rollers, a consideration on a shaft drive bike where owners are more likely to fit fairings that reflect engine noise back at the rider. Much higher oil pressures are required to lubricate plain bearings, however, so the 650G uses a heavier duty oil pump than either the E model or the old 550, its higher pumping pressure creating a slight horsepower drain at operating rpm. Such miniscule power losses of course are of little importance to those who would choose the shaft over the chain drive. In any case, the G makes plenty of power, as we’ll see.

Elsewhere the engine follows normal Japanese inline Four practice, with double overhead cams acting on shimmed buckets. The shims are on top of the buckets for easier changing and adjustment. Like the 550, the 650 uses only two valves per cylinder, but the combustion chamber is an all new design, machined into what Suzuki calls a Twin-Dome chamber.

The small combustion chamber has been cut into three concave pockets, one for each valve and one for the spark plug. The valves are slightly offset in the chamber with the exhaust valve closer to the center of the engine. In addition to helping swirl the incoming mixture, this offset allows the spark plug to crowd in closer to the center of the combustion chamber. Central location of the plug, as in fourvalve heads, is not possible, but by using the small D-type (12mm) plug and moving the exhaust valve slightly inward, a near central location is possible for balanced flame propagation.

The very small combustion chamber gives the engine a high 9.5:1 compression ratio, even with the use of relatively flat topped pistons, up from 8.6:1 on the 550, which uses a more heavily domed piston. Suzuki says the flatter piston produces better power, the piston dome creating less interference with the gas flow dynamics of the incoming mixture. This combustion efficiency and clean burning means the engine can run a high compression ratio on low-lead gas without detonation, while giving excellent fuel mileage. We can’t argue with the results; we were unable to provoke any pinging, even doing heavyhanded roll ons using super low-cal gas, and our average mileage was just a shade under 60 mpg.

Suzuki technical advisors told us they were very proud of this cylinder head design, as it was the result of emperical testing where countless subtle changes in combustion chamber shape were tried and scrapped until the correct combination was found, rather than putting the head into production on the advice of a computer and its single design. They found that opening the valve pockets slightly from the chosen shape created unwanted surface turbulence in the incoming mixture, and narrowing it any more shielded the valves too much and upset the advance of a smooth flame front in the chamber.

Like the late model 550s, the 650 has helical primary gears for reduced noise, and also comes with a fair amount of rubber blocking between the cylinder fins for the same reason. Viewed from the front, the cooling fins and cam cover on the 650’s head and barrel are cast to perform essentially the same function as the old RamFlow cooling system did on Suzuki’s earlier two-strokes. The vertical fins are shaped to funnel the air past head and barrel hot spots, and vertical fins on top of the head turn the air flow toward less exposed areas.

Ignition is electronic—no points to set—with a pair of permanent magnets set on the stationary backing plate. The centrifugal advance mechanism is identical to that used on the earlier 550’s points setup, but now has a small ferrous arm rotating on the end of its shaft instead of a points cam. Elsewhere in the low maintenance department, the cam chain tensioner is automatic and the engine oil level is checked, by current practice, at a small window in the right side of the crankcase.

The Suzuki draws its air and fuel through four 32mm Mikuni CV carbs, which work very well indeed on the new bike. When the 650 is started cold on full choke the carbs have the usual Suzuki propensity to set the engine roaring and racing at an rpm that has you visualizing oil pressure bypass valves being blown off their seats. But playing with the steering head-mounted choke button during the first half minute of warmup will keep the revs at a sane level until the engine is ready to settle down and idle. After that the engine runs fine and can be ridden away with very little choke and no trace of hesitation or other lean carb blues. We love to test bikes where the carbs work as well as the 650G’s because it saves us a lot of time in coming up with alternate jet and needle recommendations for readers whose bikes are out there staggering and lunging around the nation’s highways. There were virtually no flat spots in our test bike’s carburetion under any running conditions, and the warmup time to responsive running is blessedly brief.

Air filtration for the carbs is handled by an oiled foam element, accessible under the right sidecover. Cleaning is done by removing the foam sock from a coneshaped plastic cage, rinsing in solvent and reoiling. The side of the airbox is held on by two sliding clips, one of which is a little hard to reach during filter replacement, but the system is otherwise strong and simple.

The G and GL model 650s share a newly designed shaft arrangement Suzuki calls its Direct-Link system. In this setup the pinion gear, which turns the driveshaft, is located directly on the end of the transmission mainshaft, rather than on the layshaft or a separate jackshaft, as is more typical of shaft bikes. In the first four of the 650’s five gears power goes from the mainshaft to the layshaft and then back to a gear at the end of the mainshaft which rotates independently of the others and drives the pinion gear. But when 5th gear is selected that independent gear is coupled directly to the mainshaft, so there are no spare shafts or gears in play. Power from the primary gear goes directly through the mainshaft to the pinion gear and driveshaft.

This arrangement makes for a very simple transmission and final drive assembly and also eliminates unnecessary slop in the drive train when the bike is in high gear. An added advantage is narrowness; because the pinion gear is on the mainshaft it can be inboard of the driveshaft and still turn it in the correct direction for forward motorcycle movement. When the pinion gear is coupled to a transmission layshaft it must be located outboard of the drive shaft to get the correct drive rotation. The inside placement simplifies gear and bearing layout, making the transmission case lighter and narrower; moving the drive pinion forward also makes it shorter.

Most of the shaft drive Suzukis have been very good about minimal drive train lash in the past, particularly the GS1000G, even without the Direct-Link system. The GS650G follows that tradition with an exceptionally tight and nonclunky drive train. There is very little noticeable lash, even in the lower gears. Get on the power and all you feel from the drive line is a slight rise at the rear end, a torque reaction from the ring and pinion gears.

Solid drive train hookup is just one favorable element that adds to the tight, unified road feel of the bike. Everything works crisply and the GS is one of those bikes that seem to have been made from one piece, rather than many loosely jointed pieces. Starting the motorcycle and riding it away, a low level of growling vibration is felt between 3000 and 4000 rpm while accelerating up through the gears, but once cruising speed is reached and maintained in any gear the vibration level smooths out so as to be almost unnoticeable. At highway cruising speed the low growling sound is still there, mixed in with the wind noise, but the footpegs and handlebars are nearly free from the tingling and gnawing found in some midsized Fours. Backing off the throttle in any gear produces a certain amount of twittering and whirring of the gears common to shaft drive bikes, but the sound is a lot nicer when unaccompanied by clunking and drive train slop.

Other than added weight, unsprung and otherwise, which is always a slight drawback to shaft drive bikes, the Suzuki’s only real shaft-related fluke is a tendency for the rear end to bob and dip a bit in hard corners if the rider displays grave indecision with the throttle. Steady state cornering is smooth and untroubled, and a firm, progressive roll-on while exiting a corner produces only a mild, predictable rise from the back end.

Our general pleasure with the 650’s street handling led us to ride it out to Willow Springs Raceway to see if wringing it out on the track would produce any surprises. Our only real surprise was how well the bike handled—better than a couple of supposed sport bikes we’ve had on the track recently—and how smoothly and comfortably it could be ridden at box stock racing speeds. The 650 felt agile and compact for its displacement and handled transitions from one corner to the next with ease.

The Suzuki’s rear suspension has a pair of shocks with five-position adjustable spring preload and an external collar allows the rider to quickly dial in one of four possible shock damping rates. The collar is large, clearly marked and clicks from one position to the next with little wrist effort. The outer collar operates a pair of small spur gears that turn a rod which runs down the center of the shock body. The rod has a disc on the end with four holes drilled in it, large to small. Turning the disc rotates different holes into line with the shock’s oil orifice, changing oil flow restriction and damping.Z

With rear springs and damping on full soft the ride is comfortable for a solo rider, but hard throttle application produces noticeable (and visible, to bystanders) climband-wallow torque reaction in corners; on full damping and preload the bobbing influence of the shaft is nearly absent, even on the race track.

The front fork tubes are equipped with separate air caps, for which the owner’s manual recommends a 7.1 psi dose of pressure, with a maximum of 14.2 psi permitted. Most riders will probably find fiddling with the air caps unnecessary once normal pressure is set unless they add fairings and other weight for touring. With 7.1 psi in the tubes the standard spring rates and damping on the 650 work fine for normal use and have none of the soft, diving habits exhibited by earlier GS550s and 750s under hard braking. It would be nice, however, if the GS had a balance tube between the two air caps. Filling forks legs with small amounts of air pressure is an imprecise procedure at best, and a healthy percentage of the pressure can be lost each time a gauge is used. It’s always hard to get the pressure at exact recommended specs, but at least with a balance tube you know the fork legs are equally, if a little inexactly, pressurized.

The GS650’s brakes are very good; the stopping distances we recorded during testing, 32 ft. from 30 mph and 141 ft. from 60 mph, are about normal for the class. The 650’s three 10.75 in. slotted discs provide a lot of swept area, 287.7 sq. in, and as is often the case where a bike has plenty of braking power, the tires and road surface provide most of the limitation on stopping distance. Tires on the 650 are Mag-Mopus Bridgestones, a 3.25 H-19 front and a 4.25 H-17 rear, provide fairly good traction for OEM tires and were noteworthy during the braking tests and many laps around Willow Springs for their lack of unpleasant surprises. They were predictable through fast corners, and even improved slightly as they heated up.

At the lever end of the system, the Suzuki’s brakes are easy to modulate, having a good effort-to-tire-smoke ratio. The rear brake seems touchy at first riding, locking up the rear tire easily during lowspeed stops in city traffic, but after a few miles of familiarity it seems merely powerful and useful.

Shift action is also above par. From a dead stop the transmission was occasionally hesitant to engage first from neutral when the engine wasn’t fully warmed up. Once warm however, the Suzuki accepts downshifts with almost servo-action ease, and the lever action in either direction is short and succinct. In a day at the drag strip and a full day at Willow Springs, none of the three testers who rode the bike missed a shift. Ratios in the five-speed gearbox are well spaced, and using the gearbox is made easier by the 650’s broad power band.

Performance for the 650, like its brakes, transmission and handling, is good. Our test bike ran through the quarter mile in 12.91 sec. at 101.46 mph. The only 650 we’ve tested which betters that figure is Yamaha’s Midnight Maxim, which was only a hair faster and quicker with a 12.84 sec. 101.8 mph run. Happily, the Suzuki’s power is not all top end rush, but is distributed generously through the bike’s working rpm range. Lugged down in top gear, the GS will pull strongly from 3000 rpm on up. For normal city riding there’s plenty of power to be had between 3000 and 5000 rpm, with little need to run the needle higher. But for passing cars or working out a bad case of sheer exuberance, the engine will get down and pull seriously all the way to its 9500 rpm redline, and a little beyond. At 60 mph the engine is turning about 4600 rpm, from which it will pull well enough to take most hills and pass most cars on the highway, even two-up. But when passing takes on a note of urgency, 4th gear gives the rider an extra 700 rpm and a very healthy boost in acceleration.

While 4th makes an excellent passing gear, the GS has incredibly good midrange for a 650 and doesn’t demand a lot of shifting to keep the engine from falling on its face. Our top gear roll-ons with computer gear aboard produced some eyeopening figures; the GS accelerates from 40 to 60 mph in 4.8 sec., or exactly the same amount of time as its slightly quicker quarter mile competitor, the Yamaha Midnight Maxim. But the Suzuki covers ground in the 60 to 80 mph (passing) range half a second faster than the Yamaha, 5.6 sec. versus 6.1 sec. It also out-accelerates the HondaCB750C in that range; the Honda we tested in Oct. 1980 took 5 sec. to go from 40 to 60 and 6 sec. from 60 to 80. Good mid-range makes a bike fun to ride because it’s the kind of performance you can feel, rather than the kind that shows up only on the quarter mile clocks. The Suzuki’s willingness to pull was another factor that made fast, smooth laps at Willow Springs so easy; it comes out of corners hard even with the revs below peak power.

At 59.6 mpg the Suzuki 650 joins that modern league of high performance Fours that serve up mileage figures you can brag about along with low E.T.s and high top speeds. The 59.6 mpg was on our mileage loop, which typifies normal city/highway riding speeds; trying to get from Willow Springs to L.A. before sundown while wearing a dark face shield netted 44 mpg, that figure attained at roughly 1.6 times the national speed limit. Still not bad. Normal cruising gives the Suzuki a 189 mi. range to reserve, and about another 40 mi. to empty. Our Suzuki brochure said the bike had a 4.5 gal. tank and the owner’s manual said 4.2, but try as we might we couldn’t squeeze more than 3.9 gal. into the empty tank.

Long distance between fillups won’t be too much of a problem with the GS as it is a comfortable bike to ride. The seat is properly padded, even without that contemporary overstuffed sofa look, and the passenger portion got hearty acclaim from a weekend guest. The footpegs and handlebars are both well located; pegs in that middle ground between full custom windup-the-pantlegs and racer’s crouch; the handlebars similarly non-extreme. Performance minded riders thought the bars could be a bit lower and farther forward and others thought they were just about right, especially considering that many shaft bike customers like to mount fairings and have less problem with wind pressure while riding. Opinions aside, everyone was able to ride the Suzuki without backache or wrist failure.

Finish on the GS is excellent, and nearly all who looked at the bike commented that it was a nice clean design, tastefully painted and happily lacking in false glitter and exaggerated styling flourishes. The tank shape received favorable comment from one staff member who said it looked traditionally Suzuki, reminiscent of the Titan era.

Instrumentation is simple; separate tach and speedometer with a small idiot light panel between them. The instrument faces are easy to read at night, with red numerals that are backlit in what Suzuki calls Astro-lighting. There is a two-way helmet lock, beneath the left side of the seat with separate rings for two helmets so they can be removed one at a time rather than having one crash to the ground while you do a saving catch on the other. A nice touch.

In the marketplace of 650cc motorcycles the Suzuki has a lot going for it. The bike comes in three distinct forms; sport, shaft and shaft Low-Slinger, unlike the Yamaha Maxim which is available only ih Special trim, so there is something for, everyone. It offers a bit more performance than the Honda CB650, again with the option of shaft drive. The gas tank is large enough to put some distance between fillups; the seat is comfortable, yet not so severly stepped that rider movement if impaired, and suspension settings allow a wide range of comfort and performance adjustments. At 493 lb. the GS is heavier than either the Maxim or the Honda 650, but it handles that weight very well and still gets excellent fuel economy. It is compact without being small, agile, about as, fast as anything in its class and has a broad power band that makes city, canyon road, or open highway riding a pleasure.

We couldn’t find much to dislike about the GS650G. It is a well-conceived machine where everything works just a little better than it has to. Some test bikes feel fine at first and then begin to chip away at the rider’s enthusiasm as small irritants and quality problems surface; other bikes also feel right at first and then go on feeling right, winning the owner’s continued enthusiasm as the miles pile up on the odometer. The GS650G belongs in the latter group. An excellent motorcycle.

SUZUKI

GS65OG

$2749

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontInnocence Vanquished, Fatherhood Victorious

June 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1981 -

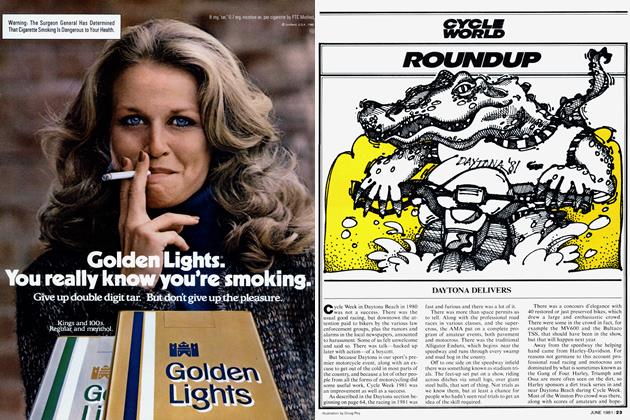

Department

DepartmentRoundup

June 1981 -

Competition

CompetitionDaytona'81 Speed, Fame, Sand And Sweet Magnolia

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Competition

Competition200-Mile Formula One

June 1981 By John Ulrich -

Daytona'81

Daytona'81The Battle of the Twins

June 1981 By Peter Egan