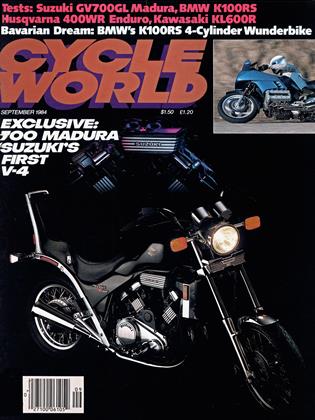

SUZUKI GV700GL MADURA

CYCLE WORLD TEST

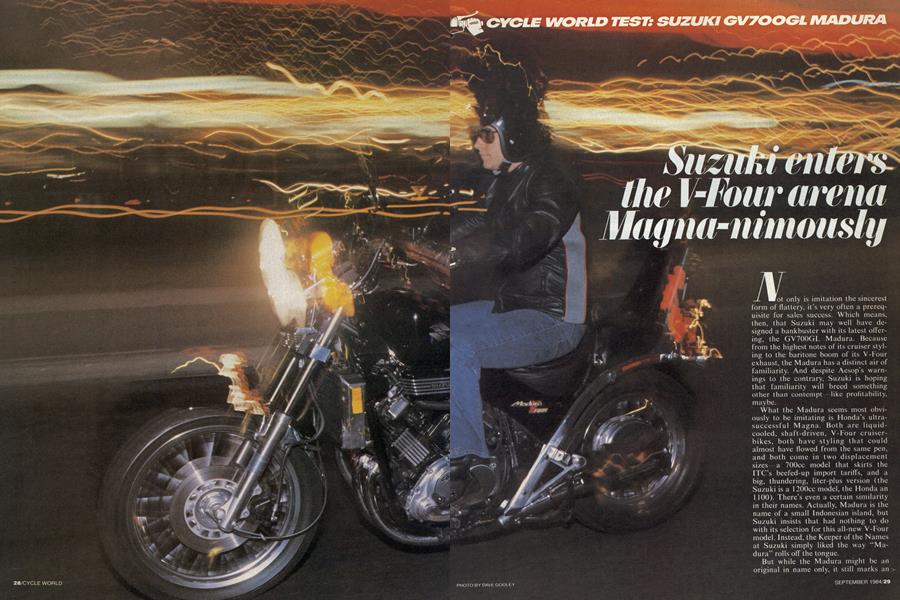

Suzuki enters the V-Four arena Magna-nimously

Not only is imitation the sincerest form of flattery, it’s very often a prerequisite for sales success. Which means, then, that Suzuki may well have designed a bankbuster with its latest offering, the GV700GL Madura. Because from the highest notes of its cruiser styling to the baritone boom of its V-Four exhaust, the Madura has a distinct air of familiarity. And despite Aesop's warnings to the contrary, Suzuki is hoping that familiarity will breed something other than contempt like profitability, maybe.

What the Madura seems most obviously to be imitating is Flonda’s ultrasuccessful Magna. Both are liquidcooled, shaft-driven, V-Four cruiserbikes, both have styling that could almost have flowed from the same pen, and both come in two displacement sizes a 7()0cc model that skirts the ITC’s beefed-up import tariffs, and a big, thundering, liter-plus version (the Suzuki is a 1200cc model, the Honda an 1 100). There’s even a certain similarity in their names. Actually, Madura is the name of a small Indonesian island, but Suzuki insists that had nothing to do with its selection for this all-new V-Four model. Instead, the Keeper of the Names at Suzuki simply liked the way “Madura” rolls off the tongue.

But while the Madura might be an original in name only, it still marks an> important milestone in Suzuki history. It is the company's first departure from aircooled street engines since the GT750 two-stroke triple was phased out back in 1977, and the first departure from inline engines since the ill-fated Rotary of a few years earlier. And just as Suzukis of recent years have been accused of adding to the proliferation of UJMs (Universal Japanese Motorcycles, i.e. inline-Fours), so too will some people now claim that the Madura and the Magna are forerunners of the UJC (Universal Japanese Custom, i.e. V-Four cruiser).

True or not, that claim gains some credibility if you consider all of the hardware similarities between the two bikes; because even though various design details diller, the fundamentals do not. The Magna and Madura engines look alike and are built similarly, w ith double overhead camshafts, four valves per cylinder, and liquid-cooled, cast-iron cylinders cast integrally w ith the upper half of horizontally split crankcases. The 698.5cc Suzuki's bore and stroke measure 69mm by 46.7mm, which is just marginally less oversquare than the 70mm-by-45.4mm dimensions on the 698.9cc Flonda. Each engine uses a 360-degree crank, meaning that it has both of its crankshaft throws (each throw carries the two connecting rods on its side of the engine) on the same axis. The two parallel pairs of pistons therefore rise and fall in unison (the two fronts together, the two rears together), with each pair firing alternately every revolution.

A significant advantage of a V-Four’s crankshaft over an inline-Four's is that it is lighter an important factor, considering that the crank is an engine's heaviest component. The Madura’s crank, which is almost identical to the Magna's, looks like it belongs in some 400-class vertical-Twin, for it is only about twothirds the width and less than half the weight of its counterpart in a GS750 inline-Four.

There are, however, two noteworthy, differences between Magna and Madura engines: the angle and location of their vee-spreads. The Honda’s cylinder banks >are at 90 degrees to one another, with the forward bank almost on a horizontal plane and the rear bank almost vertical; the Madura’s cylinders are angled at 82 degrees in a symmetrical fashion, with each bank angled41 degrees from vertical.

Suzuki wouldn’t specify exactly why an 82-degree angle was chosen, but we suspect it has something to do with Honda holding a Japanese patent on 90degree V-four motorcycle engines. Having a less-than-90-degree vee-spread causes the Madura to emit a bit more engine vibration than the Magna does, inasmuch as V-type engines can achieve their much-acclaimed perfect primary balance only when their cylinder banks are at 90 degrees. But that added vibration is so small, and is so well cushioned by the Madura’s rubber engine mounts, that it’s not worth worrying about.

Neither must you worry about valve adjustment on the Madura, for it has automatic valve-lash adjusters that never require attention. That’s a first for a Suzuki but Honda’s Nighthawk 640 and other select Honda motorcycles had it first. And in truth, automobile engines and Harley-Davidson Big Twins have used similar hydraulic lash-adjusters (called hydraulic lifters or hydraulic tappets in those applications) for decades. The difference is that in H-D and automobile engines, the lifters move up and down with the valve train, while in the Madura and Magna, the hydraulic lash adjusters are stationary, acting only as pivot points for the finger-type cam followers. That lack of movement allows the adjusters to continue operating at extremely high rpm, whereas the type that must constantly jiggle up-and-down generally stop working at a fairly low rpm. So even though the Madura has an extremely high (10,750-rpm) redline, its adjusters have no trouble keeping up.

Aside from its method of valve adjustment, the Madura’s cylinder-head design has little in common with the Magna’s. The head incorporates the patented Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber (TSCC) configuration introduced on inline-Four Suzukis several years ago, with a 38-degree included angle between the intake valves and the exhausts. The Madura’s method of driving its camshafts also differs from the Magna’s. The Honda uses two independent cam chains, one for the two cams atop the front cylinders, another for those atop the rear's, and each chain runs right down to the crankshaft through the middle of the engine, between its respective pair of cylinders. The Suzuki, however, has three chains. One is geared to the crank at the right side of the engine and drives a short jackshaft that’s situated just above the upper engine case at the base of the cylinders’ vee-spread. From there, the cam drive is much like the Honda’s, with a single, Hy-vo-type chain running between each pair of cylinders up to its respective camshafts.

Suzuki chose this method of cam drive for two reasons, despite the complexity it adds (three chains and three automatic tensioners rather than two each, plus an idler shaft and bearings, and a handful of chain guides). For one, shorter chains can be used, which helps extend the life of the chains and tensioners. Also, because the Suzuki’s system is driven from the right end of the crankshaft (with a sprocket splined onto the end of the crank) rather than from the middle, there’s no need to machine a gear in the middle of the crank. Not only does that save considerable manufacturing expense, it also allows the engine to be a bit narrower.

Aside from that, however, there is little about the Madura engine, designwise, to differentiate it from the Magna. Both have a hydraulically actuated clutch, both use CV carburetors (33mm downdraft Mikunis on the Madura, 34mm downdraft/sidedraft Keihins on the Magna) that are fed by an electric fuel pump, and both employ a six-speed gearbox that has an unusually tall “overdrive” top-gear ratio. One difference is that the Suzuki’s intermediate gearcase (the spiral-bevel reduction that turns the power 90 degrees at the rear of the engine) simply bolts on, whereas the Honda’s is built in. And with the Madura’s gearcase removed, it’s easy to see how, with a shorter transmission countershaft and an appropriate sprocket, this V-Four could be converted to chain final drive. Does that mean Suzuki has a V-Four, chain-drive sportbike up its new-model sleeve?

That’s a hard question to answer right now. But based on the way it performs, the Madura engine could do a morethan-respectable job in a full-on sport machine. Its quarter-mile times (12.89 seconds, 102.96 mph) indicate that the 700cc Madura is not quite as fast as most 750s, but that’s to be expected, given its displacement handicap. Besides, the Madura is a not a racebike in any sense of the word; and out on the highways and byways in real-world situations, the Madura feels fast. Its power output is almost linear from idle to redline, with no flat spots to disappoint, no sudden surges of power to catch you unawares. So when you roll open the throttle, the bike simply moves out quickly and instantaneously, accelerating at what seems like a constant rate.

In addition, the Madura is a typical VFour in that it offers excellent low-end and mid-range wallop, which is much more useful for most types of riding than having a rush of top-end acceleration. The Suzuki’s power is immediately accessible, meaning that you don’t have to break-dance on the gearshift every time you want to pick up the pace. Granted, the Madura’s roll-on acceleration in top gear is not forceful enough to give anyone whiplash, but that’s mostly because the ratio in sixth gear is quite tall.

Despite all their similarities, though, the Madura and Magna engines don't sound that much alike. The Magna, like all Honda V-Fours, has a rather flat, lackluster note whose pitch doesn’t change much between idle and redline; but the Madura’s exhaust note has some teeth, beginning with a sharper, deeper burble at idle and progressing to a soulful wail as the revs approach the 10,750rpm redline. The small difference in veespread isn’t enough to account for such a dramatic difference in sound; so one must assume that the Madura’s distinctive rumblings are due primarily to the particular way in which its exhaust system is tuned.

Once away from the engine, you find even more dissimilarities between the Madura and the Magna although the feeling of déjà vu is always with you. The basic lines of the Suzuki parallel those of the Honda teardrop-shaped, 3.4-gallon gas tank, pullback handlebar, stepped seat, built-on sissybar/passenger backrest, fat rear wheel, shorty mufflers but the Madura uses a Full Floater single-shock rear suspension rather than dual rear shocks like on the Magna. The Honda V-Four cruiser is fitted with castaluminum wheels, while the Suzuki has wire-spoke wheels. And instead of having the usual number of spokes (either 36 or 40), the Madura has 60 chromeplated spokes in its 19-inch front wheel and 56 in its 16-inch rear; not only that, all the spokes are machined flat on their outer sides so they'll sparkle and glitter as they reflect the light.

What’s more, rather than being made of conventional roundor trendy boxsection tubing, the Madura’s frame cradle is constructed of hexagonal steel tubes. You read it right: That’s six-sided tubing. There is no functional reason for the use of this tubing other than pure styling to be “different,” as a Suzuki spokesman put it.

That it is. But despite any deliberate, Hollywood-nights glitziness, the Madura’s chassis works quite well. Its steeringgeometry numbers (29.5-degree head angle, 4.57 inches of trail) don’t suggest ultra-quick steering, but the Madura is surprisingly agile and easy to turn anyway. Much of that is due to engine placement, which is lower on the Suzuki than on the Honda Magna. That lowers the center of gravity, making the relatively heavy Madura feel lighter than it actually is (543 pounds with a half-tank of fuel), whether maneuvering through congested traffic at a walking pace or hustling around a corner at high speed.

Only when the Suzuki is pushed hard through a corner does its custom-bike chassis come up short. The riding position is classic cruiser stuff bolt-upright, with forward-mounted footpegs and a wide, swept-back handlebar which might offer the ideal posture for trolling urban boulevards but not for fast running along stretches of twisty blacktop. Also, the same low engine placement that makes for such light steering also allows bits of undercarriage to start gouging the pavement rather early when you get serious about straightening out a winding backroad. Matter of fact, you can drag the usual itemscenterstand feet, sidestand, footpegs just turning into many steep driveways, especially when traveling two-up or even riding solo with the rear suspension set near the soft end of its preload range. And no matter where the rear preload is set, there's not enough rebound damping (there are no provisions for damping adjustment) to keep the rear end from bobbing and weaving during any attempts to play roadracer.

But winning backroad playraces is not what the Madura was intended to do. It was designed to perform competently at less-frenetic tasks, and at that it is superb. As long as you don’t decide to stalk Interceptors and Ninjas with it, the GV700GL will bend around corners with amazing agility and reassuring stability, never indicating that you have asked more of the bike than it can deliver. For a pseudo-chopper, it actually conducts itself quite well in the twisty-turnies, offering a pleasant balance between strong acceleration, spirited cornering and dependable braking that is hard to find serious fault with.

Even the suspension behaves admirably when the bike is ridden in a less-thanbanzai manner. The overall ride generally is quite plush, with only the sharper, more-abrupt bumps ever finding their way up to the rider. And if bigger riders, or those sharing the Suzuki's two-piece seat with a passenger, determine that they're hitting bottom too often, a couple> of easy-to-use adjustments have been provided. For one, the leading-axle front fork has air fittings on the cap nuts to permit fine-tuning of the front suspension rates; and a remote adjuster located on the left, just above the swingarm pivot, allows quick changes in rear-shock spring preload by merely turning a knob. A small window above the knob displays the preload setting in numbers from 1 to 5, with four-and-a-half turns required to effect a one-digit change in the setting. All in all, the ride never rivals that of a good full-dress touring rig, but all-day sits in the saddle won’t pummel you, either.

Some of that comfortability is derived from the fact that, for a bike with such obvious cruiser intentions, the Madura has a reasonable seating position and a rational control layout. The seat itself or the rider’s segment of it, at least is nicely shaped and amply padded, which allows it to keep the rider’s buns from being numbed on fairly long rides. Most riders should be able to last a tankful of gas (about 100 to 125 miles on the average) before starting to squirm around on the seat; and the amount of time required for a fill-up and a quick Coke is enough of a recuperative period to prepare him for another tank’s distance.

His passenger, however, might be ready to throw in the towel after the first tank. The rear segment of the seat is hard and narrow, the passenger pegs are 'too high, and the backrest on the sissybar is too short to offer any real support and angled too far backward to be comfortable. That’s one area where comfort took a backseat to style. Literally.

But as far as the rider is concerned, the Madura is thoroughly non-abusive. There’s just enough vibration evident from time to time to let you know that the engine is running, but never enough to numb your extremities or stop the images in the rear-view mirrors from being dead-sharp. And the reach to the oversize, soft-rubber handgrips is just about right for anyone with normal-length arms if, of course, you embrace the kind of riding position that typifies these kinds of custom-style motorcycles. If you don’t, you’ll find the traditional cop-like, upright position annoying, if not unacceptable.

There’s nothing annoying about the Madura’s control switches and instrumentation, though. It’s all fairly straightforward UJC stuff, with a traditional analog speedometer and tach resting just above a small panel that houses the usual warning lights, a low-fuel light, a coolant-temperature gauge, and a simple, bulb-type gear-position indicator. The handlebar switches are of a style that’s new to Suzuki, sort of a combination of traditional Japanese and contemporary Harley-Davidson, but they work without a glitch.

Suzuki did, however, buck tradition by equipping the Madura with a one-inchdiameter handlebar—a size formerly used only by Harley-Davidson—rather than the usual 7/8-inch bar. That’s a questionable decision, for it means that all of the other handlebar bends, handlebar levers and handlebar control switches that Suzuki dealers now stock won’t fit the Madura.

Those dealers might find that a particularly aggravating turn of events, but if the Madura lives up to expectations and there’s no reason to think that it won't they’ll be more than happy to grin and bear it. Things haven’t been so prosperous for Suzuki dealers recently, and the prospect of a hot new model, one that just might make a noticeable dent in the lucrative custom market dominated by Honda’s Magna and Shadow, must seem like money from home. That the Madura is a good, competent, thoroughly enjoyable motorcycle is simply a bonus, even if it’s not the quickest, the fastest, the best-handling—or even an original.

The truth is that while the new Madura might not turn the hottest laps out on Racer Road or set quick E.T. at the dragstrip, it’ll more than likely set fast time out of the showroom. And in the end, those are the numbers that really count.

$3549

SUZUKI

GV700GL MADURA

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

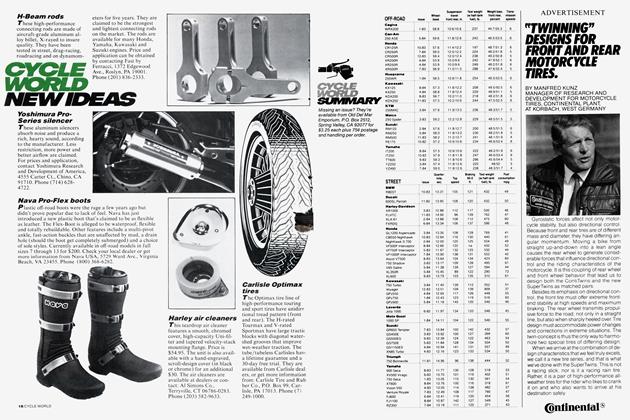

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Features

FeaturesThe Widow

SEPTEMBER 1984 By David Edwards -

Features

FeaturesLong-Term Test: Harley-Davidson Fxrs

SEPTEMBER 1984