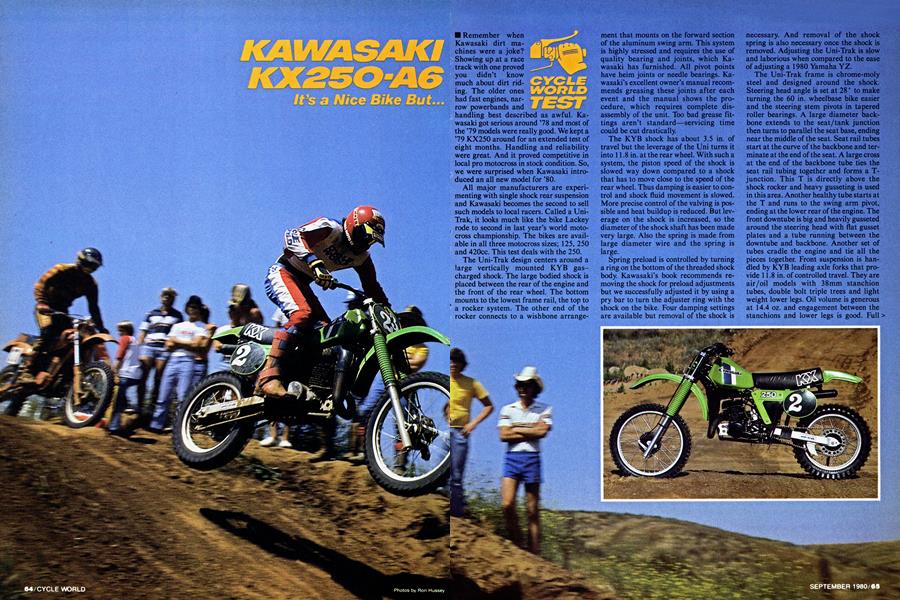

KAWASAKI KX250-A6

1t's a Nice Bike But...

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Remember when Kawasaki dirt machines were a joke?

Showing up at a race track with one proved you didn’t know much about dirt riding. The older ones had fast engines, narrow powerbands and handling best described as awful. Kawasaki got serious around ’78 and most of the ’79 models were really good. We kept a ’79 KX250 around for an extended test of eight months. Handling and reliability were great. And it proved competitive in local pro motocross in stock condition. So, we were surprised when Kawasaki introduced an all new model for ’80.

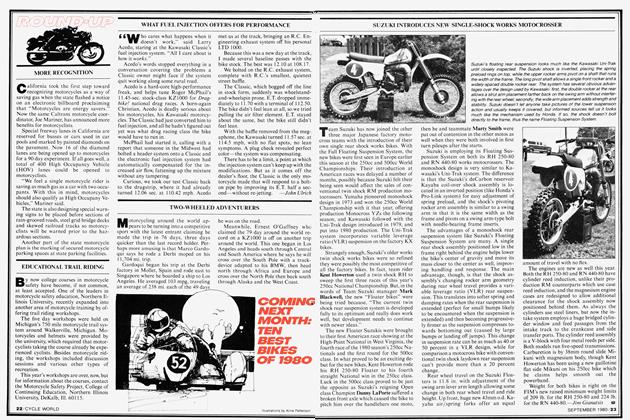

All major manufacturers are experimenting with single shock rear suspension and Kawasaki becomes the second to sell such models to local racers. Called a UniTrak, it looks much like the bike Lackey rode to second in last year’s world motocross championship. The bikes are available in all three motocross sizes; 125, 250 and 420cc. This test deals with the 250.

The Uni-Trak design centers around a large vertically mounted KYB gascharged shock. The large bodied shock is placed between the rear of the engine and the front of the rear wheel. The bottom mounts to the lowest frame rail, the top to a rocker system. The other end of the rocker connects to a wishbone arrange-

ment that mounts on the forward section of the aluminum swing arm. This system is highly stressed and requires the use of quality bearing and joints, which Kawasaki has furnished. All pivot points have heim joints or needle bearings. Kawasaki’s excellent owner’s manual recommends greasing these joints after each event and the manual shows the procedure, which requires complete disassembly of the unit. Too bad grease fittings aren’t standard—servicing time could be cut drastically.

The KYB shock has about 3.5 in. of travel but the leverage of the Uni turns it into 11.8 in. at the rear wheel. With such a system, the piston speed of the shock is slowed way down compared to a shock that has to move close to the speed of the rear wheel. Thus damping is easier to control and shock fluid movement is slowed. More precise control of the valving is possible and heat buildup is reduced. But leverage on the shock is increased, so the diameter of the shock shaft has been made very large. Also the spring is made from large diameter wire and the spring is large.

Spring preload is controlled by turning a ring on the bottom of the threaded shock body. Kawasaki’s book recommends removing the shock for preload adjustments but we successfully adjusted it by using a pry bar to turn the adjuster ring with the shock on the bike. Four damping settings are available but removal of the shock is

necessary. And removal of the shock spring is also necessary once the shock is removed. Adjusting the Uni-Trak is slow and laborious when compared to the ease of adjusting a 1980 Yamaha YZ.

The Uni-Trak frame is chrome-moly steel and designed around the shock. Steering head angle is set at 280 to make turning the 60 in. wheelbase bike easier and the steering stem pivots in tapered roller bearings. A large diameter backbone extends to the seat/tank junction then turns to parallel the seat base, ending near the middle of the seat. Seat rail tubes start at the curve of the backbone and terminate at the end of the seat. A large cross at the end of the backbone tube ties the seat rail tubing together and forms a Tjunction. This T is directly above the shock rocker and heavy gusseting is used in this area. Another healthy tube starts at the T and runs to the swing arm pivot, ending at the lower rear of the engine. The front downtube is big and heavily gusseted around the steering head with flat gusset plates and a tube running between the downtube and backbone. Another set of tubes cradle the engine and tie all the pieces together. Front suspension is handled by KYB leading axle forks that provide 11.8 in. of controlled travel. They are air/oil models with 38mm stanchion tubes, double bolt triple trees and light weight lower legs. Oil volume is generous at 14.4 oz. and engagement between the stanchions and lower legs is good.. Full > rubber boots protect oil seals and the handlebar pedestals are rubber mounted.

The ’80 KX250 engine is a combination of old and new; the bore and stroke are the same (70 x 64.9mm) and the rod assembly is the same as last year’s bike. The cylinder is also unchanged except for small porting changes aimed at increasing the width of the powerband. The cylinder still uses a non-borable Electofusion surface. The carburetor is a 38mm Mikuni. Fuel intake is via fiber reeds made by Boyesen. The main cases are new. The cases are smaller and the countershaft sprocket is rear-set. Last year’s bike had the countershaft placed 4.9 in. from the swing arm pivot, the ’80 measures 3.1 in. The closer placement means chain tension will change less with rear wheel movement and elaborate chain guide systems aren’t needed to keep from throwing the drive chain. Internal transmission ratios are almost the same as the ’79 but several other differences are noticeable. The large clutch no longer rides on needle bearings; a bronze sleeve has replaced it. And the shifting mechanism is different. It looks much like the system Suzuki has used on the RMs since 1975, but has more parts. Most of the shifting parts are in the end of the shift drum and the drum is rotated by a ratchet and pawl device. The design works great on RMs but poorly on the KX, due to quality control of the parts. Our bike wouldn’t shift out of third under hard acceleration most of the time. Disassembly showed the ratchet assembly was flawed by an out-of-round spring cavity in the ratchet piece. One of the two spring loaded pins would stick in the ratchet and fail to move the shift drum. The ratchet is extremely hard and redrilling in an attempt to make the cavity round proved futile as the part is harder than drill bits. We ground on it with a stone bit and got it to work for a short time but it had to be replaced before shifting was correct. The part was an obvious second and should not have left the plant.

As long as we are talking about problems and screw-ups we may as well talk about the air cleaner element. It’s made from a good foam and has a large filtering surface until the side plate is installed ... then the side plate sits against the face of the filter and eliminates over half of the usable filter surface. The edge of the filter can be completely clogged with dirt and the face will be completely clean because dirt and air can’t get to it. A shallower filter would let air to the face and increase the usable filter area. The rest of the air box shows excellent engineering and thought. The side cover fits into a recessed groove in the box, ensuring a tight waterproof seal and the air inlets at the top are placed so air enters and water stays out.

Front and rear wheel assemblies are the same as last year. The brakes are strong and progressive and don’t lock the suspension when used hard on rough ground, but

they don’t match the stopping power of the new YZs. Spokes don’t look overly large but loosened less than any motocrosser we have tested during the last year.

All the plastic parts on the KX are new. The rear fender still has the chopped look but it’s longer than before and does a good job. The front fender keeps water and muck off the rider better than any we can

remember. The side panels and tank are reshaped and the cap has a recessed vent. All controls are placed right and comfortable. The seat is narrow but not too narrow. Footpegs are unchanged and still don’t have strong enough return springs. The expansion pipe is new and routed so it doesn’t burn the rider and a large silencer is fitted. But the exhaust note is loud. The 1980 KX looks a lot different than last year’s bike. Not only from an engineer’s eye but from a consumer view of The finished product. Last year the KX had a custom look; the aluminum swing arm and wheel rims were gold anodized, the tank brackets were cast aluminum, the head stay was aluminum, as was the brake pedal and many other small pieces. The

swing arm on the 80 is aluminum but the custom finished look and anodizing are gone. The color-matched grips and lower fork leg protectors have also disappeared. And most of the small aluminum pieces just mentioned have been replaced with steel parts. The weight difference is marginal but the difference in the look of the finished product is great. Not that the ’80

looks bad, or cheap, it doesn’t. It has, however, lost the one-off custom look.

Jumping aboard a KX will cause almost anyone to stretch to touch the ground. With a seat height of 38.4 in. the bike is best described as mountainous. And the stiff rear shock doesn’t sack to lower the height once on the bike, which makes it feel even higher. The KX starts easy and warm up is rapid. Clutch pull is easy and the bike pulls away from a dead stop without jerking or stalls. The top-of-the-world feeling is overwhelming for a couple of hours then everything seems normal until the rider tries to touch the ground with the bike on a small knoll or hump and finds he can’t. After falling over a few times the rider begins to look for a berm or rock to stop next to so one foot has a spot easily reached.

If you weigh less than 200 lb. the first bump will tell you the shock preload is too much. The back doesn’t move much until a large jump is encountered or something really bad is hit. Small bumps and ripples are treated as if the rear of the bike didn’t have suspension—the stiff spring simply doesn’t move for them. We backed the spring preload off about half an inch. The difference in compliance to small bumps and ripples was amazing.

The book recommends 4 psi pressure in the forks and we found that just right. Once the suspension was dialed, the bike becomes much nicer to ride. With a 60 in. > wheelbase you wouldn’t expect the KX to turn well, but just the opposite is true. It makes square turns beautifully. In fact, square turns are almost required to make the bike work properly. The 28° rake makes turning easy and the long wheelbase makes straight line control excellent. Bermed turns are something else. Full concentration on the part of the rider is necessary when using a berm. Everything seems fine half way through and everything is fine if the throttle is kept on hard. If not, the bike will drift over the lip. Both wheels slide over so gradually that the rider isn’t aware it is doing it until too late. It’s damn scary when it happens, too. Changing tires helps. We put a 3.00-21 Metzeler on the front, a 4.60-18 Dunlop K190 on the rear. The difference in the bike’s control was astonishing. Control

improved everywhere but predictability in berms was the best improvement. The bike didn’t require as much attention and if the bike started to ride out of the berm, the rider was aware of what was happening and could make corrective maneuvers.

The KX250 Uni-Trak is different through whoops and overjumps. Tracking through whoops is straight and sure. And its manners over jumps are beyond reproach. The bike doesn’t go straight up, instead it stays low and shoots off the jump, easily outdistancing normal suspensions. But turning the throttle on as the rear wheel hits the top of the jump (the rider has excellent feel of the rear wheel over jumps) the bike will shoot away at a low altitude. When conditions aren’t right and the rider has to chop the throttle over a jump, the bike doesn’t kick or show other

bad manners, it just goes over the obstacle.

Although the large bodied shock is equipped with a remote reservoir, the shock will fade noticeably when pushed by a pro for over 30 min. Damping declines as does control when severe heating occurs but control isn’t hampered to the point of being dangerous, it’s just noticeable.

By far the best feature of the bike is the engine. Power and powerband are fantastic for a 250. It comes on the pipe at low revs and the power continues in a nice smooth plane until it runs out of breath. No surges or sudden explosions, just smooth, predictable power and a lot of it. The powerband is much like that of a 350cc engine and total power output is nearly as good. The transmission ratios are perfect for the engine and final gearing is also right on. Although the KX only has a five-speed transmission, there's no bog or jump between any of the ratios. Studying the overall gear ratios of the KX gives an indication of the engine's power output. Low is 20.11:1 and fifth is 9.43:1. The ratios wouldn't be wrong for a much larger motor and the 250 wouldn't pull these ratios without an abundance of torque.

KAWASAKI

KX250-A6

$1849

We entered the KX in a local motocross and a grand prix. The rider competed in the pro class at both events, the motocross first. The bike was left in stock trim and finished third for the event. Control with the stock tires spooked the rider and he didn't have the confidence to push the bike to a better finish. The tires were changed before the grand prix and the KX smoked to first overall in a field of 40 riders includ ing 15 open bikes. Tires make a tremen

dous difference in handling on the Uni Trak. Fuel mileage is good and 45 mm. motos can be raced with a pro rider aboard with no fear of running out of gas.

Problems and breakage on the KX were few Besides the shifting, the only break age was the steel head stay. It broke the first race. The head stay on our long range `79 KX broke several times also. Perhaps the change from aluminum to steel for the strap was an effort at eliminating the breakage problem. If it was, it didn't. No use replacing it with a stock part, just make a new one from a thick piece of strap steel or aluminum and solve the problem.

competitive, we liked the `79 with dual shocks better. The `80 has a better power band, in fact it'll be hard to find any make with a wider, more predictable power-

band. But the `79 didn't have the handling problems in bermed turns, nor did the rider have to fight the bike or allow for handling quirks anywhere on the track or trail. It was just as competitive and much easier to ride. It lacked the complexity of the Uni-Trak and maintenance was straightforward and simple. Not so with the Uni. Lubrication of the rear suspen sion parts requires disassembly (before and after each event if the owner's manual is followed) when grease fittings would have simplified the job, and adjustments for rear shock spring preload and damping is harder and slower to perform than nec essary. No doubt these problems will be eliminated in future models but a buyer of a 1980 KX250 will have to live with them. Given the choice of a `79 dual shock KX or a new single shocker, we'd take the `79.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHere At Cycle World

September 1980 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1980 -

Roundup

RoundupTesting On the Move

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpMore Recognition

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpEducational Trail Riding

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpWhat Fuel Injection Offers For Performance

September 1980 By John Ulrich