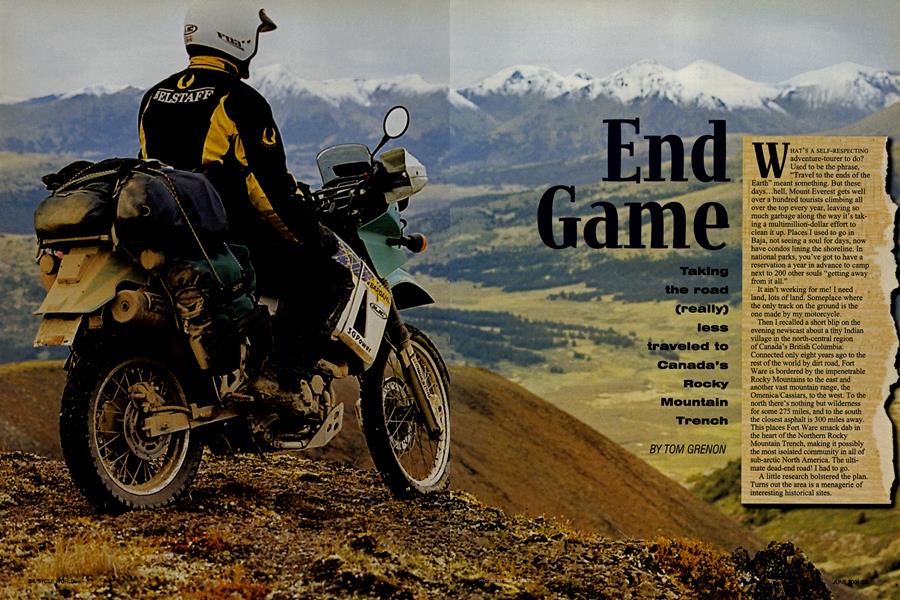

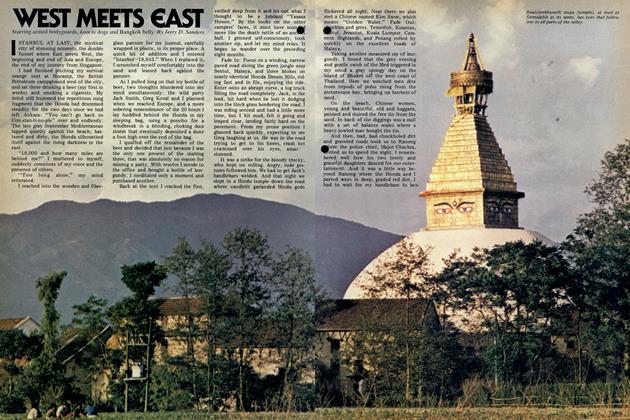

End Game

Taking the road (really) less traveled to Canada's Rocky Mountain Trench

TOM GRENON

WHAT'S A SELF-RESPECTING adventure-tourer to do? Used to be the phrase, "Travel to the ends of the Earth” meant something. But these days... hell, Mount Everest gets well over a hundred tourists climbing all over the top every year, leaving so much garbage along the way it’s taking a multimillion-dollar effort to clean it up. Places I used to go in Baja, not seeing a soul for days, now have condos lining the shoreline. In national parks, you’ve got to have a reservation a year in advance to camp next to 200 other souls “getting away from it all.”

It ain’t working for me! I need land, lots of land. Someplace where the only track on the ground is the one made by my motorcycle.

Then I recalled a short blip on the evening newscast about a tiny Indian village in the north-central region of Canada’s British Columbia. Connected only eight years ago to the rest of the world by dirt road, Fort Ware is bordered by the impenetrable Rocky Mountains to the east and another vast mountain range, the Omenica/Cassiars, to the west. To the north there’s nothing but wilderness for some 275 miles, and to the south the closest asphalt is 300 miles away. This places Fort Ware smack dab in the heart of the Northern Rocky Mountain Trench, making it possibly the most isolated community in all of sub-arctic North America. The ultimate dead-end road! I had to go.

A little research bolstered the plan. Turns out the area is a menagerie of interesting historical sites.

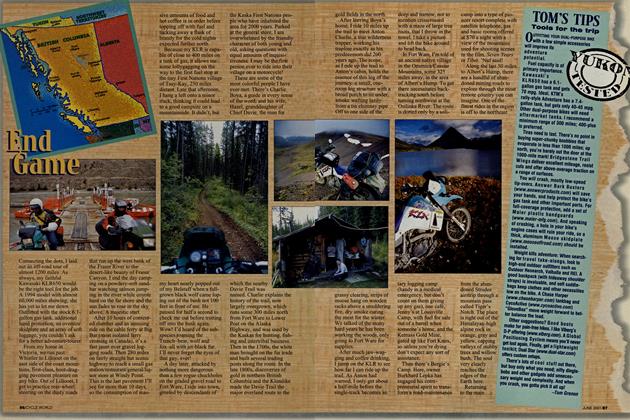

Connecting the dots, I laid out àn off-road tour of almost 1200 miles. As always, my faithful Kawasaki KLR650 would be the right tool for the job. A 1994 model with almost 60,000 miles showing, she has yet to let me down. Outfitted with the stock 6.1gallon gas tank, additional hand protection, an oversize skidplate and an array of soft luggage, you couldn’t ask for a better adventure-tourer.

From my home in Victoria, we run past Whistler to Lillooet on the east side of the coast mountains, first-class, boot-dragging pavement pleasure on any bike. Out of Lillooet, I get to practice rear-wheel steering on the dusty roads

that run up the west bank of the Fraser River to the desert-like beauty of Fraser Canyon. I end the day camping on a powdery-soft sandbar watching salmon jumping in the river while coyote hunt on the far shore and the sun fades to rose in the sky above. A majestic start.

After 10 hours of contented slumber and an amusing ride on the cable ferry at Big Bar (most isolated ferry crossing in Canada), it’s a fast jaunt over gravel logging roads. Then 280 miles on fairly straight but scenic highway to reach a small gas station/restaurant/general/liquor store at Windy Point. This is the last pavement I’ll see for more than 10 days, so the consumption of mas-

sive amounts of food and hot coffee is in order before topping off with fuel and tucking away a flask of brandy for the cold nights expected further north.

Because my KLR is capable of close to 400 miles on a tank of gas, it allows me some lollygagging on the way to the first fuel stop at the tiny First Nations village of Tsay-Kay, 250 miles distant. Late that afternoon,

I hang a left onto a minor track, thinking it could lead to a good campsite on a mountainside. It didn’t, but

my heart nearly popped out of my Belstaff when a fullgrown black wolf came loping out of the bush not 100 feet in front of me. He paused for half a second to check me out before trotting off into the bush again. Wow! I’d heard of the subspecies roaming the Trench-bear, wolf and fox-all with jet-black fur.

I’ll never forget the eyes of that guy, ever!

A day later, attacked by nothing more dangerous than a few rogue chuckholes on the graded gravel road to Fort Ware, I ride into town, greeted by descendants of

the Kaska First Nations people who have inhabited the area for 2000 years. Parked at the general store, I am overwhelmed by the friendly character of both young and old, asking questions with equal amounts of inquisitiveness. I may be the first person ever to ride into their village on a motorcycle!

These are some of the most colorful people I have ever met. There’s Charlie Boya, a guide in every sense of the word, and his wife, Hazel, granddaughter of Chief Davie, the man for

which the nearby Davie Trail was named. Charlie explains the history of the trail, now largely overgrown, which runs some 300 miles north from Fort Ware to Lower Post on the Alaska Highway, and was used by the Kaskas for hunting, fishing and intertribal business. Then in the 1700s, the white man brought on the fur trade and built several trading posts along the route. In the late 1800s, discoveries of gold in northern British Columbia and the Klondike made the Davie Trail the major overland route to the

gold fields in the north.

After leaving Boya’s home, I ride 10 miles up the trail to meet Anton Charlie, a true wilderness trapper, working his trapline exactly as his predecessors did 200 years ago. The scene, as I ride up the trail to Anton’s cabin, holds the essence of this leg of the joumey-a small, oneroom log structure with a broad porch to sit under, smoke wafting lazily from a tin chimney pipe. Off to one side of the

grassy clearing, strips of moose hang on wooden racks above a smoldering fire, dry smoke curing the meat for the winter. We talked of the many hard years he has been working the woods, only going to Fort Ware for supplies.

After much jaw-wagging and coffee drinking, I jump on the KLR to see how far I can ride up the trail. As Anton had warned, I only get about a half-mile before the single-track becomes so

deep and narrow, not to mention crisscrossed with a maze of large tree roots, that I throw in the towel. I take a picture and lift the bike around to head back.

In Fort Ware, I’m told of an ancient native village in the Omenica/Cassiar Mountains, some 325 miles away, in the area of Albert’s Hump. To get there necessitates backtracking south before turning northwest at the Osilinka River. The route is dotted only by a soli-

tary logging camp (handy in a medical emergency, but don’t count on them giving up any gas), one café, Jenny’s at Louisville Camp, with fuel for sale out of a barrel when someone’s home, and the Kemass Gold Mine, gated up like Fort Knox, so unless you’re dying don’t expect any sort of assistance.

Then there’s Bergie’s Camp. Here, owner Burkhard Lepka has engaged his entrepreneurial spirit to transform a road-maintenance

camp into a type oí pioneer resort complete with

satellite telephone, gas and basic rooms offered at $70 a night with a view of the mountains used for shooting scenes in the film, Seven Years in Tibet. ’Nuf said!

Along the last 50 miles to Albert’s Hump, there are a handful of abandoned mining roads to explore through the most remote country you can imagine. One of the finest rides in the region is off to the northeast

from the abandoned Strudee airstrip through a mountain pass called Tiger’s Notch. The place is right out of the Himalayas-high alpine rock in orange, gray and yellow, capping valleys of stubby trees and willow bush. The soul very clearly reaches the edges of the Earth here.

Returning to the main route, I ride up Lawyer’s Pass, then down to the Toodoggone River before a rapid climb onto the vast plateau of Albert’s Hump. Almost as if on cue, the gray afternoon sky starts breaking up. Slogging through all the rain and mud becomes no more than a minor penance for being here in the midst of this sublime wilderness. I slowly ride as though entering a holy temple until I reach the northern edge of the plateau. Quickly taking a few photos in case the weather suddenly turns bad, I then hike up to the very top “hump.” There, a piled-rock grave with a eulogy on a plaque holds the world still. “Go rest high on that mountain, son, your work on Earth is done,” it reads. As final resting places go, you could do a lot worse.

Camping on the plateau for the night, I am rewarded with crystal clear skies and a phenomenal display of Northern Lights consuming the entire sky in giant waves of green and blue light, rolling from horizon to horizon. Unfortunately, the next morning brings a cold rain driven by nasty winds. Heeding the warning, I reluctantly pack up, wishing the weather were not so unusually cool and wet. But this far north and at a 6000-foot elevation, you take what you can get. Mother Nature is pushing me away before I have a chance to search out the 100-year-old abandoned village of Metsantan, hidden deep in one of the valleys below.

That I leave for another day.

To add entertainment value on the return, I throw a right at the Osilinka River junction, taking old, seldomused logging roads to a small cluster of cabins called Germansen Landing. Along with cabin rentals and food, gas from a barrel can be purchased at the old general store. Warming by the wood stove, jawing with the locals (population: 35) is like slipping into the Wayback Machine dialed to 1935. Talk is about horses and mining rather than megabytes and deadlines. The only concession to the 21 st century is the satellite phone hanging on the wall.

Further proof that even at the ends of the Earth, you can run but you can’t hide. Good fun trying, though. □

A resident of British Columbia, photographer Tom Grenon helps fellow dualpurpose riders find new ways to explore remote areas via his website, www. motorcycleexplorer. com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTrouble By the Beach

June 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAt the Edge of Magic

June 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving Museum

June 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2001 -

Roundup

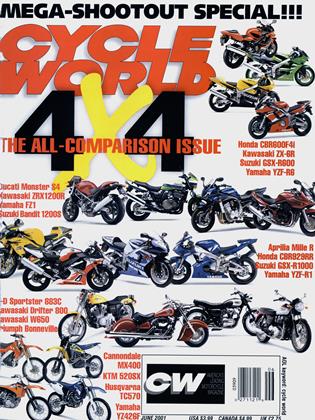

RoundupComing Soon: Next Year's Knockouts

June 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFuture-Think Mxer

June 2001 By Jimmy Lewis