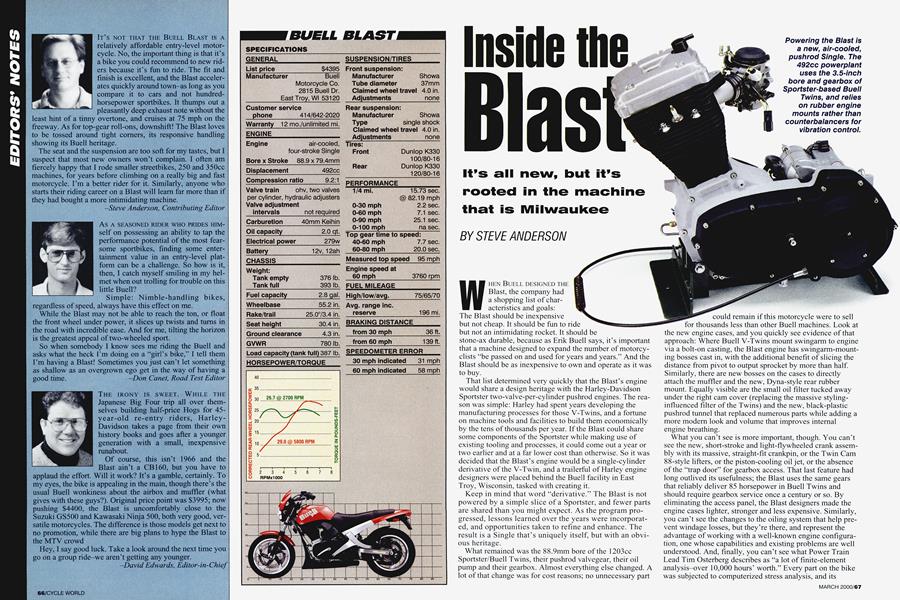

Inside the Blast

It's all new, but it's rooted in the machine that is Milwaukee

STEVE ANDERSON

WHEN BUELL DESIGNED THE Blast, the company had a shopping list of characteristics and goals: The Blast should be inexpensive but not cheap. It should be fun to ride but not an intimidating rocket. It should be stone-ax durable, because as Erik Buell says, it’s important that a machine designed to expand the number of motorcyclists "be passed on and used for years and years." And the Blast should be as inexpensive to own and operate as it was to buy.

That list determined very quickly that the Blast’s engine would share a design heritage with the Harley-Davidson Sportster two-valve-per-cylinder pushrod engines. The reason was simple: Harley had spent years developing the manufacturing processes for those V-Twins, and a fortune on machine tools and facilities to build them economically by the tens of thousands per year. If the Blast could share some components of the Sportster while making use of existing tooling and processes, it could come out a year or two earlier and at a far lower cost than otherwise. So it was decided that the Blast’s engine would be a single-cylinder derivative of the V-Twin, and a trailerful of Harley engine designers were placed behind the Buell facility in East Troy, Wisconsin, tasked with creating it.

Keep in mind that word “derivative.” The Blast is not powered by a simple slice of a Sportster, and fewer parts are shared than you might expect. As the program progressed, lessons learned over the years were incorporated, and opportunities taken to refine and enhance. The result is a Single that’s uniquely itself, but with an obvious heritage.

What remained was the 88.9mm bore of the 1203cc Sportster/Buell Twins, their pushrod valvegear, their oil pump and their gearbox. Almost everything else changed. A lot of that change was for cost reasons; no unnecessary part

could remain if this motorcycle were to sell for thousands less than other Buell machines. Look at the new engine cases, and you quickly see evidence of that approach: Where Buell V-Twins mount swingarm to engine via a bolt-on casting, the Blast engine has swingarm-mounting bosses cast in, with the additional benefit of slicing the distance from pivot to output sprocket by more than half. Similarly, there are new bosses on the cases to directly attach the muffler and the new, Dyna-style rear rubber mount. Equally visible are the small oil filter tucked away under the right cam cover (replacing the massive stylinginfluenced filter of the Twins) and the new, black-plastic pushrod tunnel that replaced numerous parts while adding a more modem look and volume that improves internal engine breathing.

What you can’t see is more important, though. You can’t see the new, short-stroke and light-flywheeled crank assembly with its massive, straight-fit crankpin, or the Twin Cam 88-style lifters, or the piston-cooling oil jet, or the absence of the “trap door” for gearbox access. That last feature had long outlived its usefulness; the Blast uses the same gears that reliably deliver 85 horsepower in Buell Twins and should require gearbox service once a century or so. By eliminating the access panel, the Blast designers made the engine cases lighter, stronger and less expensive. Similarly, you can’t see the changes to the oiling system that help prevent windage losses, but they’re there, and represent the advantage of working with a well-known engine configuration, one whose capabilities and existing problems are well understood. And, finally, you can’t see what Power Train Lead Tim Osterberg describes as “a lot of finite-element analysis-over 10,000 hours’ worth.” Every part on the bike was subjected to computerized stress analysis, and its weight optimized scientifically.

When it came to tuning the Blast’s engine, the process relied less on computer analysis than “blind rider taste tests,” as described by Erik Buell. A 492cc displacement was chosen early in the program as offering enough power capability with good smoothness through its relatively short stroke, but its exact state of tune was under test and discussion until several months before production. Sample groups of riders rode different Blasts equipped with various cam profiles, with peak output varying from a 34-horse version with a fairly peaky powerband (SI cam profile) to 30 horses with a very fat torque profile (Sportster Sport cam profile). The overwhelming pick was for the torquier, lower-horsepower version, which is what made production.

The chassis that carries the engine was designed with as much focus on value as the engine. Utilizing a rectangular backbone that serves as the oil tank, the frame is composed of tubular and sheetmetal parts in a combination of

mild and 4130 chromoly steel. The engine/swingarm package floats in rubber mounts: a traditional Buell mount up by the cylinder head and a Harley Dyna Glide-style variable-stiffness mount at the rear of the engine. As on other Buells, three tie-rods constrain the engine and rear wheel to move

There’s nothing wimpy about the chassis.

According to Erik Buell, the aim was for “a very rigid chassis with great weight distribution and great brakes,”

and to stay away from typical entry-level cost-cutting on chassis components to the detriment of performance.

Instead, costs were cut by radical simplification. Check out the brake disc mounting system, for example, where the discs bolt directly to the wheel spokes without a carrier, and achieve a floating-disc effect with nothing more than wave washers and mounting bolts. Or take the bodywork: The gas tank isn’t what it appears to be; it’s actually a black roto-molded plastic piece under the colored tank cover. The tank cover, the flyscreen fairing, the front fender and the tailpiece are all injection-molded from Dupont Surlyn, a plastic with molded-in color that was originally developed for cut-proof golf-ball covers. Chrysler worked with Dupont to develop it into something that could be used for automotive bodywork without painting, and uses it on Dodge Neon bumper covers. On the Blast, the bodywork pieces come straight from chrome-plated molds with the same beautiful surface finish you see on the finished bike. And if an owner ever damages the bodywork-or just gets bored with the color-he can buy the entire set for less than the price of a Honda Rebel 250 gas tank.

Some cost-cutting led to additional benefits. Using an 18mm (about 3/4-inch) Gates toothed belt, the Blast disposes of any belt-adjustment mechanism; the rear axle fits through simple holes in the back of the swingarm. How can this be? The latest Gates belt doesn’t stretch and is manu-

factured to an extremely tight tolerance. By mounting the swingarm directly to the engine, and holding a tight tolerance on the swingarm pivot-to-axle length, Buell could build a machine that has no more need of rear-wheel adjustments than a shaft-drive bike-and no more chance of rear wheel misalignment.

At other times, money was spent to buy desired features, or trade-offs were made between performance and simple utility-with simplicity winning. The Keihin carburetor on the Blast comes with an automatic choke, a rare feature on motorcycles. It cost Buell extra, but it means that the Blast rider won’t have to worry about fiddling with a lever. Similarly, they won’t be fiddling with suspension adjustments: The Showa 37mm fork and shock offer precisely zero adjustments to confuse or intimidate someone new to motorcycling. Instead, the suspension was set-up to work reasonably well for a broad range of riders, with emphasis on a smooth ride. Buell testing found that inexperienced riders didn’t like the nervous feel of firm suspension.

In the end, the Blast is a unique engineering achievement. Carefully balancing performance with the perceived needs of inexperienced riders, Buell has aimed to create a machine of broad utility, a type of motorcycle that almost vanished with the demise of the Japanese 350/400/450cc Twins. By concentrating on value, Erik Buell has built a motorcycle that costs less than half his namesake Twins, yet offers a level of detail and finish that seems almost Japanese. That’s quite an accomplishment for an American company that’s been mass-producing motorcycles for less than a decade.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue