Café Society

UP FRONT

David Edwards

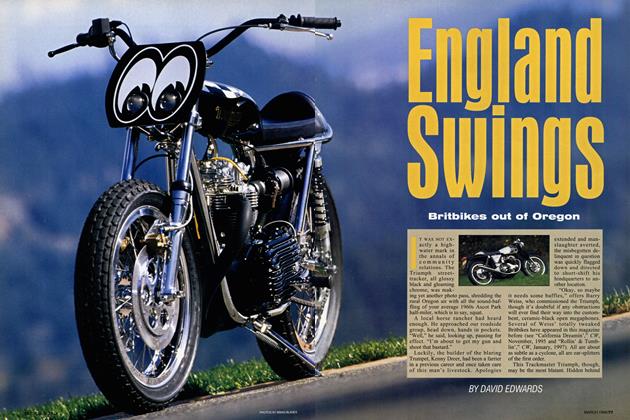

NOBODY REALLY NEEDS TWO NORTONS, of course—in fact, you can make pretty good argument that one is often more than enough. But when my friend Joe Colombero reluctantly put his 1967 Atlas 750 cafe-racer on the block, I figured it’d make a great bookend for my SS880 Dreer Commando. One a modern Norton special, the other an authentic artifact from the swingin’ Sixties. Rationalization is a wonderful thing, ain’t it?

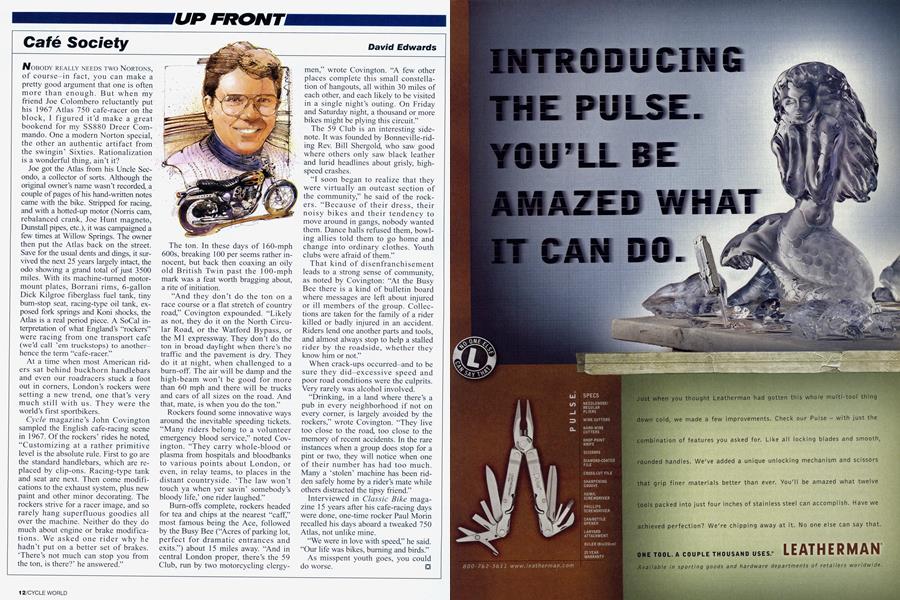

Joe got the Atlas from his Uncle Secondo, a collector of sorts. Although the original owner’s name wasn’t recorded, couple of pages of his hand-written notes came with the bike. Stripped for racing, and with a hotted-up motor (Norris cam, rebalanced crank, Joe Hunt magneto, Dunstall pipes, etc.), it was campaigned few times at Willow Springs. The owner then put the Atlas back on the street. Save for the usual dents and dings, it survived the next 25 years largely intact, the odo showing a grand total of just 3500 miles. With its machine-turned motormount plates, Borrani rims, 6-gallon Dick Kilgroe fiberglass fuel tank, tiny bum-stop seat, racing-type oil tank, exposed fork springs and Koni shocks, the Atlas is a real period piece. A SoCal interpretation of what England’s “rockers” were racing from one transport cafe (we’d call ’em truckstops) to another— hence the term “cafe-racer.”

At a time when most American riders sat behind buckhorn handlebars and even our roadracers stuck a foot out in corners, London’s rockers were setting a new trend, one that’s very much still with us. They were the world’s first sportbikers.

Cycle magazine’s John Covington sampled the English cafe-racing scene in 1967. Of the rockers’ rides he noted, “Customizing at a rather primitive level is the absolute rule. First to go are the standard handlebars, which are replaced by clip-ons. Racing-type tank and seat are next. Then come modifications to the exhaust system, plus new paint and other minor decorating. The rockers strive for a racer image, and so rarely hang superfluous goodies all over the machine. Neither do they do much about engine or brake modifications. We asked one rider why he hadn’t put on a better set of brakes. ‘There’s not much can stop you from the ton, is there?’ he answered.”

The ton. In these days of 160-mph 600s, breaking 100 per seems rather innocent, but back then coaxing an oily old British Twin past the 100-mph mark was a feat worth bragging about, a rite of initiation.

“And they don’t do the ton on a race course or a flat stretch of country road,” Covington expounded. “Likely as not, they do it on the North Circular Road, or the Watford Bypass, or the Ml expressway. They don’t do the ton in broad daylight when there’s no traffic and the pavement is dry. They do it at night, when challenged to a burn-off. The air will be damp and the high-beam won’t be good for more than 60 mph and there will be trucks and cars of all sizes on the road. And that, mate, is when you do the ton.” Rockers found some innovative ways around the inevitable speeding tickets. “Many riders belong to a volunteer emergency blood service,” noted Covington. “They carry whole-blood or plasma from hospitals and bloodbanks to various points about London, or even, in relay teams, to places in the distant countryside. ‘The law won’t touch ya when yer savin’ somebody’s bloody life,’ one rider laughed.”

Burn-offs complete, rockers headed for tea and chips at the nearest “caff,” most famous being the Ace, followed by the Busy Bee (“Acres of parking lot, perfect for dramatic entrances and exits.”) about 15 miles away. “And in central London proper, there’s the 59 Club, run by two motorcycling clergymen,” wrote Covington. “A few other places complete this small constellation of hangouts, all within 30 miles of each other, and each likely to be visited in a single night’s outing. On Friday and Saturday night, a thousand or more bikes might be plying this circuit.”

The 59 Club is an interesting sidenote. It was founded by Bonneville-riding Rev. Bill Shergold, who saw good where others only saw black leather and lurid headlines about grisly, highspeed crashes.

“I soon began to realize that they were virtually an outcast section of the community,” he said of the rockers. “Because of their dress, their noisy bikes and their tendency to move around in gangs, nobody wanted them. Dance halls refused them, bowling allies told them to go home and change into ordinary clothes. Youth clubs were afraid of them.”

That kind of disenfranchisement leads to a strong sense of community, as noted by Covington: “At the Busy Bee there is a kind of bulletin board where messages are left about injured or ill members of the group. Collections are taken for the family of a rider killed or badly injured in an accident. Riders lend one another parts and tools, and almost always stop to help a stalled rider by the roadside, whether they know him or not.”

When crack-ups occurred-and to be sure they did-excessive speed and poor road conditions were the culprits. Very rarely was alcohol involved.

“Drinking, in a land where there’s a pub in every neighborhood if not on every corner, is largely avoided by the rockers,” wrote Covington. “They live too close to the road, too close to the memory of recent accidents. In the rare instances when a group does stop for a pint or two, they will notice when one of their number has had too much. Many a ‘stolen’ machine has been ridden safely home by a rider’s mate while others distracted the tipsy friend.”

Interviewed in Classic Bike magazine 15 years after his cafe-racing days were done, one-time rocker Paul Morin recalled his days aboard a tweaked 750 Atlas, not unlike mine.

“We were in love with speed,” he said. “Our life was bikes, burning and birds.”

As misspent youth goes, you could do worse.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue