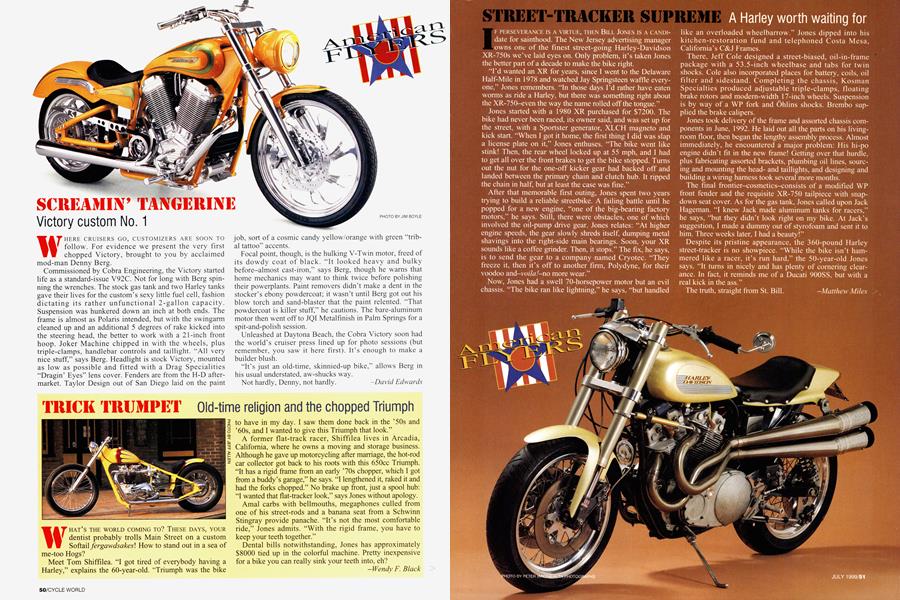

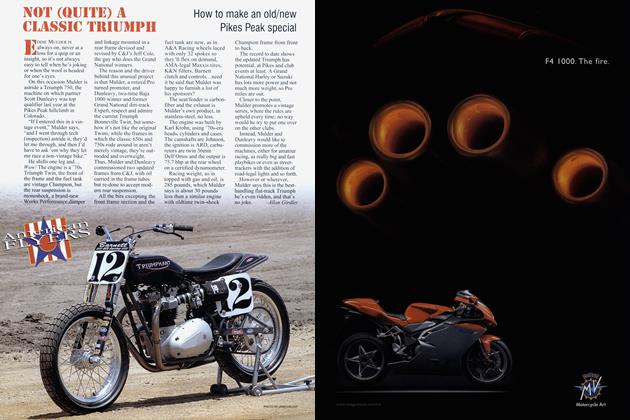

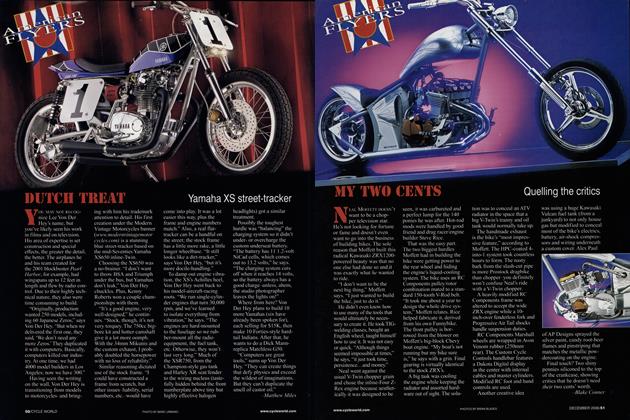

STREET-TRACKER SUPREME

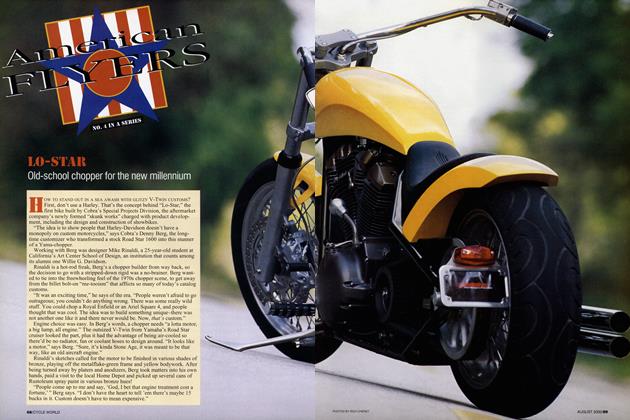

AMERICAN FLYERS

A Harley worth waiting for

IF PERSEVERANCE IS A VIRTUE, THEN BILL JONES IS A CANDIdate for sainthood. The New Jersey advertising manager owns one of the finest street-going Harley-Davidson

XR-750s we've laid eyes on. Only problem, it's taken Jones the better part of a decade to make the bike right.

'I'd wanted an XR for years, since I went to the Delaware Half-Mile in 1978 and watched Jay Springsteen waffle every one," Jones remembers. "In those days I'd rather have eaten worms as ride a Harley, but there was something right about the XR-750--even the way the name rolled off the tongue."

Jones started with a 1980 XR purchased for $7200. The bike had never been raced, its owner said, and was set up for the Street, with a Sportster generator, XLCH magneto and kick start. When I got it home, the first thing I did was slap a license plate on it," Jones enthuses. `~The bike went like stink! Then, the rear wheel locked up at 55 mph. and I had to get all over the front brakes to get the bike stopped. Turns out the nut for the one-off kicker gear had backed off and landed between the primary chain and clutch hub. It ripped the chain in half, but at least the case was fine."

After that memorable first outing, Jones spent two years trying to build a reliable streetbike. A failing battle until he popped for a new engine, “one of the big-bearing factory motors,” he says. Still, there were obstacles, one of which involved the oil-pump drive gear. Jones relates: “At higher engine speeds, the gear slowly shreds itself, dumping metal shavings into the right-side main bearings. Soon, your XR sounds like a coffee grinder. Then, it stops.” The fix, he says, is to send the gear to a company named Cryotec. “They freeze it, then it’s off to another firm, Polydyne, for their voodoo and-w/7fl/-no more wear.”

Now, Jones had a swell 70-horsepower motor but an evil chassis. “The bike ran like lightning,” he says, “but handled like an overloaded wheelbarrow.” Jones dipped into his kitchen-restoration fund and telephoned Costa Mesa, California’s C&J Frames.

There, Jeff Cole designed a street-biased, oil-in-frame package with a 53.5-inch wheelbase and tabs for twin shocks. Cole also incorporated places for battery, coils, oil filter and sidestand. Completing the chassis. Kosman Specialties produced adj ustable triple-clamps, floating brake rotors and modern-width I 7-inch wheels. S uspension is by way of a WP fork and Ohlins shocks. Brembo sup plied the brake calipers.

Jones took delivery of the frame and assorted chassis com ponents in June, 1992. 1-le laid out all the parts on his livingroom floor, then began the lengthy assembly process. Almost immediately, lie encountered a major problem: His hi-po engine didn't fit in the new frame! (ietting over that hurdle. plus fabricating assorted brackets, plumbing oil lines, sourc ing and mounting the headand taillights, and designing and building a wiring harness took several more months.

The final frontier-cosmetics-consists of a modified WP front fender and the requisite XR-750 tailpiece with snapdown seat cover. As for the gas tank, Jones called upon Jack Hageman. “I knew Jack made aluminum tanks for racers,” he says, “but they didn’t look right on my bike. At Jack’s suggestion, I made a dummy out of styrofoam and sent it to him. Three weeks later, I had a beauty!”

Despite its pristine appearance, the 360-pound Harley street-tracker is no showpiece. “While the bike isn’t hammered like a racer, it’s run hard,” the 50-year-old Jones says. “It turns in nicely and has plenty of cornering clearance. In fact, it reminds me of a Ducati 900SS, but with a real kick in the ass.”

The truth, straight from St. Bill.

Matthew Miles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue