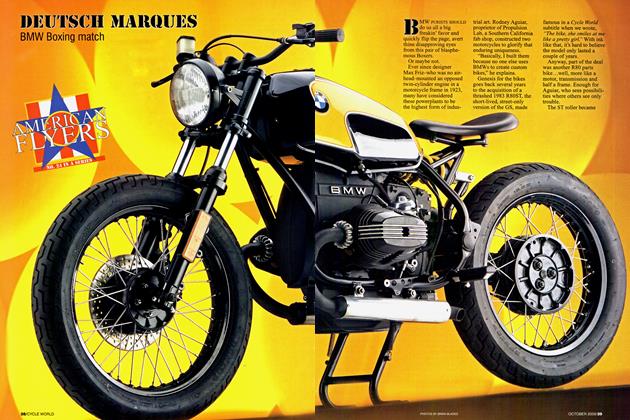

American FLYERS

LIGHTNING ROD

The V-Rod Honda could have built

WE'VE. ALL SEEN artists' conceptions depicting impossibly gorgeous motorcycles, only to dismiss them with a wave of a hand and a hearty, “Yeah, but they could never really build something like that.”

Try telling that to Ola Stenegard. designer of the custom Honda VTR 1000

Super Hawk shown here. Builder of Harley and Triumph choppers in his youth, the 32-year-old Swede approaches motorcycle design from the hands-on end of the process. He only started

sketching bikes and parts

when he realized it was easier to erase a botched drawing and start over than to try to do that in metal!

Okay, so how does some Swedish dude’s Japanese custom rate as an “American Flyer?” Good question, for which there fortunately is a good answer. Stenegard studied at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena from 1996-98, and was hired by the Indian Motorcycle Company in Gilroy in the fall of 2001, so it could be argued that he’s a Californian. Between those two dates, he worked as a junior designer at Saab in Sweden. And it was while he was there that he was approached by Swedish magazine MCM about designing a custom Japanese cruiser.

“The editor, Inge Persson-Carleson, wanted to do a I low-To series,” Stenegard recalls. “At first, he was talking about using a Suzuki Intruder, but I told him, ‘I’ve got some sketches I’d like to show you...’”

Those drawings, which Stenegard had penned while at the Art Center in ’97, were of this bike. "The VTR had just come out, and 1 was thinking. ‘There’s a really nice V-Twin, what if you built a chopper around that?”’ Stenegard remembers. “The only powercruiser then was the V-Max, and it was a V-Four. When I showed the editor my sketches, he got so fired up he bought a VTR!”

Where this project differed from traditional customs was in Stenegard’s insistence on actual production techniques. So rather than doodling a part on a napkin and roughing it out in metal, he started with a design sketch of each component, followed by a mechanical drawing with exact dimensions from which the part was made. The bodywork was even more complicated; it was first modeled in clay, then turned into negative plaster

molds and finally hand-laid in carbon-reinforced kevlar.

Two companies carried out the actual handiwork. Unique Custom Cycles started off by stripping the VTR down to its bare essentials. To achieve the raked-out look, the steering head was milled off and replaced with one machined from aluminum billet that repositioned the stem at a 40-degree angle. A set of UCC offset triple-clamps kicked out the Ceriani fork even farther, to 45 degrees.

To further extend the wheelbase, the stock rearaxle mounts were sawn off and 50mm-longer ones CNC-machined and welded on. To improve the exposed frame’s appearance, a curved bridge was welded on to cover the area above the upper shock mount.

UCC also fabricated the aluminum airbox/fuel tank, which resides under a gas strut-supported composite cover; the chrome 2-into-l exhaust system; and the two chromoly subframes one for the leather-covered solo seat and underseat radiator, the other for the hinged lower cowling, which houses a gel battery laid on its side.

At this point, the partially completed bike was trucked to I logtech, where owner Peder Johansson fitted the bodywork and fabricated the aluminum fenders, foot controls and chromoly handlebar with integral speedometer. Of course, a Swedish-built Öhlins shock was used. Finishing touch was the bright-orange candy-pearl paint with silver Dodge Viper-inspired racing stripes.

Searching for a name for his team’s creation, Stenegard hit up a Japanese co-worker who suggested “Kaminari,” which is a sort of lightning phenomenon. “It’s supposed to be very lethal,” the designer says, shaking his head.

It certainly looks it.

Brain Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMad Max Found!

May 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the Barber

May 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRoom At the Top

May 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the V-Rod: Harley's Next Revolution?

May 2002 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedici!

May 2002 By Brian Catterson