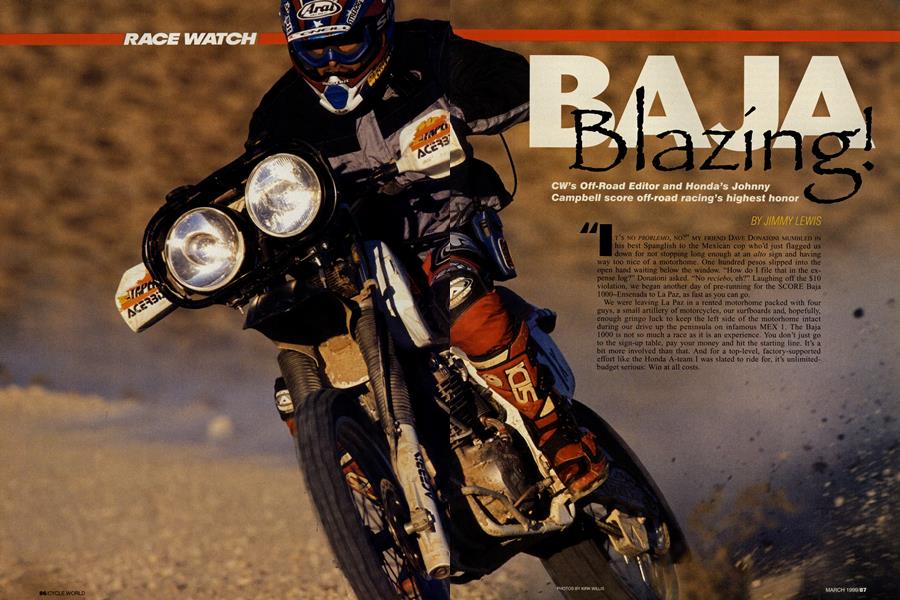

RACE WATCH

BAJA Blazing!

CW's Off-Road Editor and Honda's Johnny Campbell score off-road racing's highest honor

JIMMY LEWIS

IT'S NO PROBLEMO, NO?" MY FRIEND DAVE DONATONI MUMBLED IN his best Spanglish to the Mexican cop who'd just flagged us down for not stopping long enough at an alto sign and having way too nice of a motorhome. One hundred pesos slipped into the open hand waiting below the window. "How do I file that in the expense log?" Donatoni asked. "No reciebo, eh?" Laughing off the $10 violation, we began another day of pre-running for the SCORE Baja 1000-Ensenada to La Paz, as fast as you can go.

We were leaving La Paz in a rented motorhome packed with four guys, a small artillery of motorcycles, our surfboards and, hopefully, enough gringo luck to keep the left side of the motorhome intact during our drive up the peninsula on infamous MEX 1. The Baja 1000 is not so much a race as it is an experience. You don't just go to the sign-up table, pay your money and hit the starting line. It's a bit more involved than that. And for a top-level, factory-supported effort like the Honda A-team I was slated to ride for, it's unlimited budget serious: Win at all costs.

My pre-run group was the southern half or night-riding segment of a twoman team. My partner, factory Honda off-road racer Johnny Campbell, was 500 or so miles north doing the same thing with his crew, likely in a more orthodox (hotels, real food and no surfing) manner. Pre-running is spread over three weeks in late October and early November, riding and re-riding the course so often that you memorize every turn and are able to ride it like a motocross course, if need be, on raceday, November 12. Considering the lamentable job SCORE does of marking the course, pre-running is time well spent.

An increase in Baja population, which has resulted in more cars, more livestock and more problems south of the border, made me decide to preride with Donatoni, a seasoned Baja veteran, in case we encountered problems. The motorhome was also staffed by Bret Smith and Ryan Addison, offseason lifeguards who were lured south of the border in hopes of an allexpense-paid surfing trip. Suckers.

Initially, our days consisted of a few hundred miles of riding, with Smith and Addison either driving to meet us or sitting smack-dab in the middle of the Baja desert making sure no one stole the motorhome or its contents. Then, with plenty of daytime riding under our belts, we hit the same sections at night, the trails illuminated by giant, 100-watt headlights affixed to our XR600Rs.

We'd found a great beach and surf break to park the 27-foot Funmover, but our companions were nonetheless bored out of their minds. Their sitting idle all day waiting for Donatoni and me to reappear had the beer-consumption rate hitting critical levels. My expectations of everyone living on a strict pre-race diet of Pop-Tarts, CocaCola, Top Ramen and Tecate were a little presumptuous. And though Dave and I were operating on a nocturnal schedule, the four-men-in-a-tub sleeping arrangements and dwindling surf had tensions on the rise.

To iron out some of the pent-up frustration, we marked out "The Octagon," a two-men-enter, one-man-leaves, Ultimate Fighting-style pinnacle of conflict resolution. See, this was rookie Ryan's southernmost Baja trip, and after breaking his longboard, and being bit hard by Tequila and food poisoning, he had some issues to work out. We called it a draw after 30 minutes, as he was unable to rip my ears off or locate the pressure points that worked so well for Spock in "Star Trek."

Riding that same stretch of crappy Mexican road every day got old, despite the occasional distractions. Fike the time we passed a military Hummer full of teenage soldiers toting machine guns. We didn't stop. After all, dinner was waiting, and thoughts of the $4 combo plate at International Rice & Beans had my mouth watering for 40 miles-chiles rellenos, enchiladas, tacos and tamales never tasted so good. Of course, the other side to Baja is grazing an oncoming pickup or barely missing a cow that you never saw. That's when you get another taste in your mouth, the taste of death, and you lose your appetite. Kind of sucks the fun right out of it.

Even though Baja is like Club Med compared to Africa, it's still repressed by American standards. How else would they let us race hell-bent through the downtown streets of cities and villages? Someone got paid off, that's how. Kids love it, though. Try to keep your class of 10-year-olds in school when I come roaring past on the back wheel of a booming XR. Or how about the time we were filling up at a Pemex station, giving out a few Johnny Campbell posters, and didn't see the school bus pull up? It nearly tipped over when every kid hit the right-side windows in an effort to see the pre-running Baja Mil racers. As soon as they noticed the handouts, they spilled out of the bus like water, leaving our poster supply dry.

With race day quickly approaching, I had my sections dialed. The course was fast and in such good shape there seemed no way that we would be a threat to the Trophy trucks. These included Ivan Stewart's new eight-cylinder, 140-mph Toyota Tundra, plus the usual American horsepower monsters driven by Larry Ragland, Dan Smith and Dave Ashley.

Though the bikes are much faster through the more technical sections, the trucks with their incredible top speeds, full roll cages and portable football stadium-like lights make it much less of a fair fight than you'd imagine. In fact, the boring, slow, don't-bring-any-sponsor-money-tothe-table motorcycles rarely even make the Baja 1000 television broad casts. Thanks, SCORE.

In fact, it's a much different race than when off-road heroes Malcolm Smith and J.N. Roberts took on Baja. They never really pre-ran. Instead, they just memorized route notes and found the fastest way between check points. Pit stops required knowing at which house your support team left the jerrycan of gas. Even today, though, it's more of a race against the> biggest competitor there, the peninsula, than any other team or rider. Nailing 1000 miles without any problems is about as warped as the race's horror stories. It would be almost spooky to ride a totally clean race.

But we did. Campbell took the overall lead 40 miles into the race, then passed the bike to me at the 100-mile mark for a short 60-mile stint. He then rode another 430 miles, handing the bike back near San Ignacio where I toughed-out the last 480 miles in just under nine hours. While Campbell was on the bike, pit crews performed scheduled wheel changes and replaced the front brake pads. I never stopped for more than the standard gas stop and, after the silt beds, a new air filter. Along the way, a coyote jumped out in front of me and I skidded to avoid it. Otherwise, that's all it took to win the Baja 1000. No crashes, a few thrills and no spills.

It was a good idea to race a nearly stock XR600. An FMF muffler and an HRC power-up camshaft were the only noteworthy engine modifications. The real horsepower came in the form of the 100 or so volunteers who were scattered all over Baja completing those 10-second pit stops. Then, there were the chase-truck drivers, and the helicopter and airplane that followed us to maintain radio contact and keep the pits informed.

In the end, we beat the trucks by 10 minutes. Half-million-dollar trucks getting beat by a $6000 motorcycle. It kind of has a neat ring to it, doesn't it? Not that there was a big payoff: Campbell and I split a whopping $1600 for championing what SCORE promotes as the world's biggest off-road race. Whoopee! I made more money racing minibikes in some guy's backyard. Even more pathetic, truck driver Stewart got the big headlines in the official SCORE press release and in the Los Angeles Times for "winning" the Baja 1000. He probably made more in sponsor bonuses for placing second than I did all year.

"It's no problemo, no?" I muttered to myself. Not really, because we just won the real Baja Mil. □