RACE WATCH

The Dakar

Dreams are made of this

JIMMY LEWIS

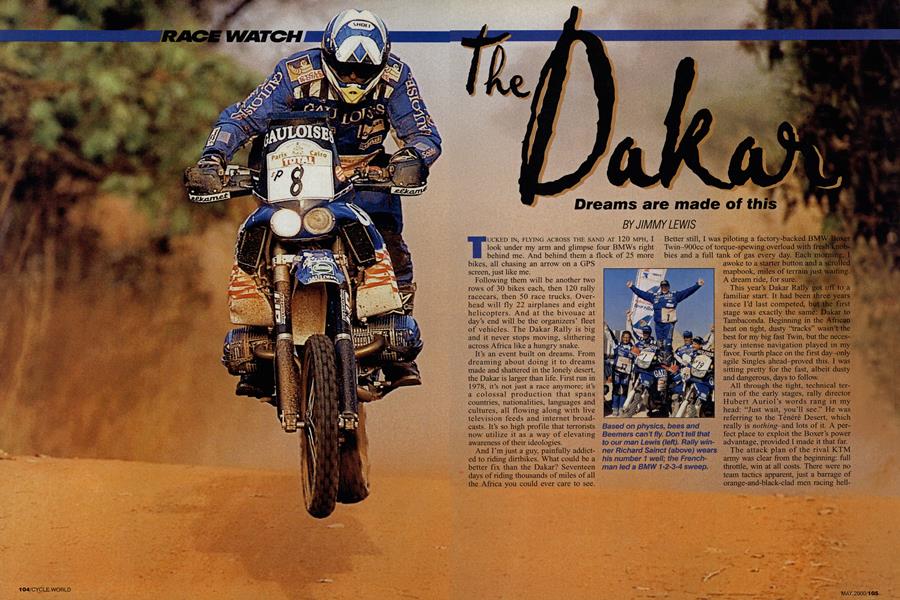

TUCKED IN, FLYING ACROSS THE SAND AT 120 MPH, I look under my arm and glimpse four BMWs right behind me. And behind them a flock of 25 more bikes, all chasing an arrow on a GPS screen, just like me.

Following them will be another two rows of 30 bikes each, then 120 rally racecars, then 50 race trucks. Overhead will fly 22 airplanes and eight helicopters. And at the bivouac at day's end will be the organizers' fleet of vehicles. The Dakar Rally is big and it never stops moving, slithering across Africa like a hungry snake.

It’s an event built on dreams. From dreaming about doing it to dreams made and shattered in the lonely desert, the Dakar is larger than life. First run in 1978, it’s not just a race anymore; it’s a colossal production that spans countries, nationalities, languages and cultures, all flowing along with live television feeds and internet broadcasts. It’s so high profile that terrorists now utilize it as a way of elevating awareness of their ideologies.

And I’m just a guy, painfully addicted to riding dirtbikes. What could be a better fix than the Dakar? Seventeen days of riding thousands of miles of all the Africa you could ever care to see.

Better still, I was piloting a factory-backed BMV Twin-900cc of torque-spewing overload with fres bies and a full tank of gas every day. Each momil

awoke to a starter button and a scrolled

mapbook, miles of terrain just waiting. A dream ride, for sure, äm #

This year’s Dakar Rally got off to a familiar start. It had been three years since I’d last competed, but the first stage was exactly the same: Dakar to Tambaconda. Beginning in the African heat on tight, dusty “tracks” wasn’t the best for my big fast Twin, but the necessary intense navigation played in my favor. Fourth place on the first day-only agile Singles ahead-proved this. I was sitting pretty for the fast, albeit dusty and dangerous, days to follow.

All through the tight, technical terrain of the early stages, rally director Hubert Auriol’s words rang in my head: “Just wait, you’ll see.” He was referring to the Ténéré Desert, which really is nothing-and lots of it. A perfect place to exploit the Boxer’s power advantage, provided 1 made it that far.

The attack plan of the rival KTM army was clear from the beginning: full throttle, win at all costs. There were no team tactics apparent, just a barrage of orange-and-black-clad men racing hell-

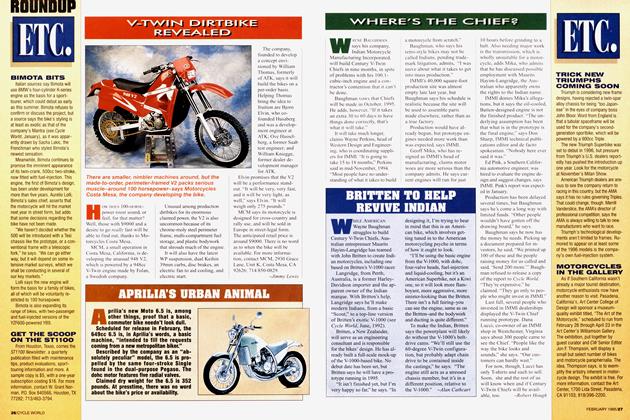

bent for the lead. Emerging at the head was the youngest of them, Spaniard Juan Roma. Setting a blistering pace in the rough and dangerous tracks of Mali, his charge to the front rewarded him with dust-free clear sailing and a lead that had even last year’s winner, BMW’s Richard Sainct, a bit concerned. Roma was running a sprinter’s pace in a longdistance race, but his track record of Dakar DNFs left doubt as to whether he would be able to hold up.

As Roma kept the heat at full inten-

sity, the rest of the KTM armada suffered trying to keep up. One by one, they dropped out with mechanical problems or crash-related injuries. Some of the best rally and enduro racers in the world-Jordi Arcarons, Kari Tiainen, Giovani Sala, Fabrizio Meoni-were forced out. Even Heinz Kinigadner, who was riding with caution very unlike his usual reckless self, crashed spectacularly out of third place while trying to catch the flying Spaniard. He was air-lifted out with a broken pelvis and assorted injuries.

But in the BMW camp everything was calm. The single-cylinder Beemer pilots were waiting, just like me, for the fast, empty deserts of the Ténéré and Libya that would allow our bikes to breathe. Though the KTMs had proven their speed and unmatched agility, the desert has a way of meld-

ing the need for velocity with the need for durability. It was a true acid test of mechanical torture I was eagerly awaiting, because at 120 mph my Boxer just loped along, hardly straining, whereas the Singles were wringing their necks hoping to keep up.

It didn’t turn out so pretty, however, as my desert dreams were put on hold by a crash on the third day. Worse, it happened right in front of a television cameraman, so it made every newsreel. >

It haunted me for the rest of the rally. The lesson: Der Boxer does not crash well. Even in this low-speed slide-out, two of the bike’s three gas tanks were cracked, necessitating time-consuming trailside repairs. Fortunately, I was able to limp in 30 minutes off the pace.

Later in the week, after I pulled 9 minutes ahead of Sainct and Roma in the day’s stage with some solid navigation, the bolt holding my Beemer’s drive-shaft torque arm broke off, likely after contacting a rock. I lucklessly sifted through the Niger Desert sand trying to find the missing part until teammate Jean Brucy stopped to help, effectively ending his chance to win the stage. Together we rigged a handguard bolt to hold the torque arm and I limped in again, another 30 minutes down the drain.

Hurting the BMW effort even more was the fact that earlier in the week, my Twin-riding teammate, Brit John Deacon, had crashed out, earning an unpleasant med-evac helicopter ride back to the organization’s mobile insta-hospital. In so doing, he balled up the only other works Boxer. It was

shaping up to be a tough rally. But that was all about to change...

At the end of the sixth stage from Burkina Faso to Niamey, Niger, we were informed that due to a terrorist threat, there was going to be a “slight” schedule change. The arrival of three giant Russian Antonov 124 transportation aircraft signaled the start of a massive airlift, organized in a matter of hours and costing the organizers a rumored $5 million. Helicopters, trucks, cars and bikes >

were loaded into the non-stop rotation of flights over the trouble zone. It was ironic, especially from an American perspective, that we were fleeing to Libya to escape terrorism!

For the 1000 or so rally participants, this meant an unwanted five-day vacation in the “garden spot” of Niamey. The delay undoubtedly paid dividends for the city’s taxi drivers and hotels, while planeload after planeload of vehicles were transported to Sabah, Libya.

For my rally game plan, this spelled disaster. Missing the wide-open Ténéré, I would have no way to make up the 90 minutes I’d lost to Roma.

Arriving in Libya, I was pleased to

find that the only cold shock was from the ambient temperature. Viewed from the plane window, the vast stretches of desert and scattered dunes looked warm and inviting. And the Libyan people weren’t cold at all. To the contrary, they were quite welcoming, a far cry from the pictures painted in news reports back home. But going from nearly 90 degrees to 40 has a way of shocking the system. For some reason-maybe the usual characteristic of the Dakar going from cold to hot, not vice versa-no one seemed ready for the temperature drop. The Boxer responded with a drained battery; it required a push-start to get going again.

The return to the routine of rally life-riding, sleeping, eating and prepping the mapbook-was welcome. We rejoined the original route with a short, 87-mile special test to get warmed back up. And here the Boxer’s almost fatal flaw was revealed: The rear foam-

rubber tire insert (called a “mousse”), intended to do away with punctures, just could not stand up to the blazing 120-mph speeds the bike so easily maintained. Though we had melted inserts earlier, it had taken 375 miles to do so; this time, it happened in just 75. This meant I had to watch my top speed, try not to spin the rear tire, and carefully choose when and where I exploited the Boxer’s power advantage. We hoped that screwing the tire to the rim would help. We hoped that the softer sandy terrain of the upcoming >

dunes would let the mousse live. But ultimately, I determined a reserved throttle hand was the best insurance and kept my enthusiasm in check.

By now, the course of the rally had been set. Roma had what he felt was a comfortable time cushion on secondplaced Sainct and began playing it safe, following the Frenchman so he couldn’t get away and make time. Oscar Gallardo was more than an hour behind in third, and I was an additional 30 minutes back in fourth, both of us standing little chance of assuming the overall lead. Meanwhile,

KTM teamsters Alfie Cox and Jurgen Mayer were busy babysitting Roma in case he needed parts or other help, while BMW’s Gallardo and Brucy were doing the same for Sainct. As the only Twin left running, I had no one to look after but myself.

During the 13th stage from Waha to Khofra, Libya, it came time to put the Boxer’s superior power to good use. I blasted out in front of everyone at the mass-start-it’s nice having the fastest bike in the rally!-then settled in with a pack of six riders at the front, all taking turns leading. About 6 miles from the stage finish, however, it was time take action. I rolled on the and dipped into that extra quarter-turn I’d refrained from using the past few days. There was nothing any of the Single riders could do. Cox tried to steal my win, but was stymied by the Boxer’s speed. Too bad I couldn’t use it all the time.

Winning a stage is a feel-

ing that doesn’t take long to sink in, and I was in heaven while riding the untimed “transfer” section to the bivouac. But seeing the excited BMW team made it even sweeter. After a 15year absence from Dakar, my stage win signified the Boxer was back!

Much to my liking, the next day featured another mass-start. The down>

side to the usual staggered start is that the leader plays navigator for the pack, only to have the guy starting from the fifth or sixth position steal the stage win based on time, without ever having to make a pass. In a mass-start, it’s heads-up, every man for himself. I darted out in front, and took turns with Gallardo finding our way to Egypt.

While we were having a relatively uneventful day, Roma and Sainct were playing rally games. Hide and go seek, stop and go, follow the leader... Every so often Sainct would come blasting by, closely followed by Roma, then we’d see them stopped by the side of the course, just sitting. This happened a few times, ’til everyone opted to go the wrong way but me. I sneaked off and rode the right way for about an hour when Gallardo and Sainct caught back up. But no Roma, and no KTM! I gave Sainct the thumbs-up and he acknowledged that everything was going okay. About 30 minutes later, he finally looked back and discovered how okay everything was! Roma was gone; his high-strung Single had finally let go.

Rolling toward the day’s finish at

120 mph, I decided that two winners would be better than one and backed off in order to let Gallardo cross the line alongside me. He had, after all, navigated for a good part of the stage-not to mention the fact that he’d let me have the hotel bed in Niamey while he slept on floor. I owed him. And if you about it, there actually were three winners that day, because Sainct was now the overall leader. It was a day of celebration in the BMW camp. All the hard had paid off. No other motorsport requires such a team

effort. From the mechanics who work on the bikes all night long, to the drivers and navigators of the four team trucks, loaded full of spares and tools, who literally race from bivouac to bivouac, often arriving after midnight and still having to get rolling early the next morning. It’s the only way to

keep everything moving-racing is the only way to keep up!

Thankfully for Roma, his support truck had kept up, but he still didn’t get back in the race until late in the night, losing hours of precious time waiting for parts to arrive. The agony of defeat was thick in the KTM

pit. Roma didn’t deserve to have his engine break-his riding had been winning the rally. Ever the trooper, he had a new powerplant installed and vowed to bounce back with stage wins (which he did) and reach the pyramids, all while holding back tears in front of the ever-present television cameras. You have to admire his dedication. For the BMW team, now holding the top four positions, the remaining Egyptian stages offered everything to lose and nothing to gain. There were never any team orders, but because we were far enough apart on time that our positions were essentially fixed, we >

just enjoyed riding together. I felt lucky to be able to roost through some of the most beautiful deserts on Earth, inaccessible by anything other than a well-equipped rally vehicle. These are the kinds of places that American desert racers fantasize about, far smoother and faster than the Mojave or Baja. Even the fastest bike isn’t fast enough; the ground is a windsmoothed canvas ready for some highhorsepower art; aim for that GPS point

and draw a line. Like I said, it’s the stuff of which dreams are made-especially for the BMW team, whose hoped-for fairytale ending had become reality. BMWs took the top four positions overall, Sainct with a second consecutive win, and the Boxer Twin on the podium in what was supposed to be just a development year.

As fantastic as it was to finish third at the pyramids after a two-week trek

across Africa, it was all but forgotten in a few days. I was kicking back at home, not riding all day long, not hearing generators running all night, sleeping in a real bed, eating three times a day, taking regular showers... The rally had become a surreal blur with only lingering memories; I had to remind myself it was real. The Dakar had gone from being a dream to ending like one. That’s what makes the Dakar the Dakar. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

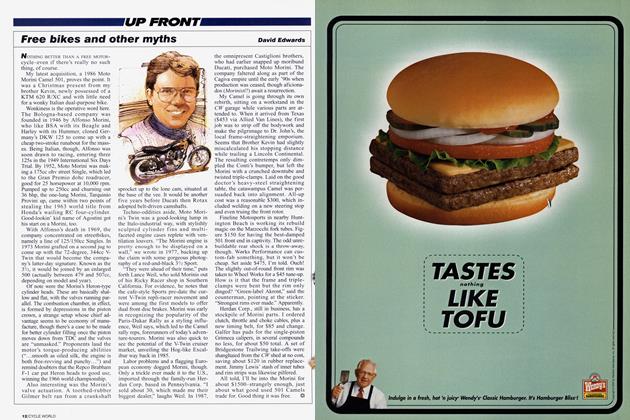

Up FrontFree Bikes And Other Myths

May 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOpening the Eastern Gate

May 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWorking All Night

May 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupTop Tourer? Honda Gl1800 Gold Wing

May 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Street-Traciker

May 2000 By Nick Ienatsch