CHARGE TO CHIHUAHUA!

Touring northern Mexico in the footsteps-and tire tracks-of the Revolution

PETER EGAN

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE ONCE SAID,"WITHOUT ITALY, Germans would go crazy." There is some evidence that Germans occasionally go crazy anyway, with or without Italy, but one can understand his meaning. Those of us who live in uptight, highly organized northern climes seem to require a place in the mind that is more relaxed and latin in temperament, where the trains do not always run on time. A warmer, more spiritual place where good food and drink temporarily induce a kind of memory loss and make time stand still. Not to mention the elevator in the hotel. Mexico, for a lot of norteamericanos, is that place.

It has been for me, for a couple of decades now. When we lived in Southern California, I fell in love with Baja and the modest, courtly good manners of its people. I became a stu dent of the place, reading books and maps and exploring the whole peninsula by motorcycle and jeep. But in all those years, I never made it to mainland Mexico.

SoT was naturally gratified and beside myself (see Dualism) when my old riding buddy Gil Nickel called from

California to say that this year's ride of the Napa Valley Touring Society (NVTS) would take us on a late-October "Charge to Chihuahua," led by Skip Mascorro of Pancho Villa Moto-Tours.

The NVTS-which, curiously, looks like "NUTS," spelled in Roman letters-is an interesting mix of people. Several members are in the wine business in Napa Valley, but the rest are from all over the U.S. and Canada. Essentially, it's just a bunch of Gil's riding pals, the only consistent theme being an irreverent sense of humor and a fierce, abiding veneration for the cocktail hour. And the several golden hours that follow, to include dinner.

Previous NVTS trips, organized by different members, had taken us through the Ozarks and the Canadian Rockies. This year's Mexico trek was orchestrated by Stan Rosow, a semi retired lawyer from Chicago who is using his spare time to explore the four corners of the Earth on a motorcycle.

After Gil invited me on this latest adventure, I walked over to my Rand McNally wall map of North America to ponder my options. The trip was to start in El Paso. All very well, but that's four days' ride from my home in Wisconsin, and four back. Added to eight days in Mexico, that was a long time away from work, deadlines and family. Too long, maybe.

Gil to the rescue. He offered me his prized yellow BMW Ki (just repainted) and said he and his wife Beth could ride their other bike, a red BMW Ri 100RS. Stan was hauling a truck load of bikes from Napa to El Paso, and there was room for one more. Perfect. I could fly to El Paso and ride from there.

So on a Friday in late October, 1 said goodbye to my long suffering wife Barbara, whose job prevented her from going along this time, and left Madison in a blinding snowstorm. The plane landed in a warm, dusty, sun-baked El Paso, where our Ryder truck full of sardine-packed motorcycles had just arrived at the Airport Hilton.

i-~ii~i ilic usuai wariii greeiiiigs aiiu iiauuuiciit cuilipil ments about not looking any older, fatter or more senile, our reunited band of 16 riders and passengers began the nerve wracking task of backing 10 bikes-eight BMWs, one Harley, one Yamaha FZR1000-down a tall ramp. Much advice, many outstretched hands (picture, if you will, the Biblical distribution of the loaves and fishes), but no fatali ties, hernias or ruined backs. Good start. - - -

LEO BESTGEN

At the hotel I met Skip Mascorro, the friendly, affable fel low who owns Pancho Villa Moto-Tours (685 Persimmon Hill, Bulverde, TX 78163; 800/233-0564), and his co-guide, Kenneth Upchurch. Interesting guys, both, with a solid background in Mexican culture.

Seems Ken Upchurch's great-grandfather, an American sugar magnate, not oniy founded and laid out the Mexican city of Los Mochis on the Gulf of California, but also helped pioneer the trans-Sierra railroad line that joined the Pacific Coast to Chihuahua. As a result of these long family ties to Mexico, he speaks Spanish so fluently I can barely understand it.

Skip is also a Mexican history buff. He's from San Antonio, but his great-grandfather was Mexican, so Skip gradually developed an interest in his Hispanic roots, traveling in Mexico and teaching himself the ways and language. It's no accident that he's named his company after Pancho Villa.

Villa, of course, was the famous Mexican revolu tionary who led American General "Black Jack" Pershing (and a young Lieutenant named George Patton) on a merry chase all over northern Mexico. President Wilson and the U.S. Army were after Villa because he supposedly crossed the border and attacked Camp Furlong, near the town of Columbus, New Mexico. in 1916.

Some historians now believe, however, that Villa didn't know about the attack and was not there. They sus pect that German emissary Franz von Papen (who much later helped bring Hitler to power) may have been behind it, in an attempt to draw Wilson's attention away from the war in Europe.

Whatever the truth, Villa is one of the great romantic and colorful heroes of Mexico, and-significantly-was once pho tographed with one foot up on the floorboard of an old F head Indian V-Twin, grinning devilishly at the camera. It's this nicture that Skin uses as the emblem of his comnany.

That first night, we decided to do a little border raid of our own, so we crossed into Juarez for dinner, taking a hotel bus to a wild, noisy place called Chihuahua Charlie's Bar & Grill.

On the way over, traffic came to a standstill. Our bus driv er explained that someone had phoned in a threat to blow up the bridge at the border. "Why would someone want to blow up the bridge?" I asked.

"They don't," he said, "but it forces the police to close the bridge and check for bombs. Then, the traffic backs up and they don't have time to check for drugs. Too many cars and trucks."

We tinally made it to (2harIie's and discovered, much to our delight, that they had a nearly inexhaustible supply of margaritas, Mexican food and guitar music, much of it served up by lovely señoritas and great big guys in concho pants and crisscrossed ammo bandoliers. We passed around a huge Mexican hat and got our pictures taken by a canny photographer who somehow detected we were tourists.

After that rehearsal, our first day of riding took us 260 miles down the U.S. side of the Rio Grande in Texas. We went east to Cornudas, then south to Van Horn and Marfa, where the 1956 movie Giant was filmed, cutting southwest toward the border on Highway 67.

All of this was on a wide-open two-lane road with almost no traffic, a mixture of purple mountains, high prairie, limitless cattle ranches, swooping arroyos and descents into broad valleys full of sweeping turns and climbs-fast, open road through a classic Western landscape, under a huge, clear West Texas sky.

Gil’s Kl did not subtract from the pleasure of this first day. Six years ago, I attended BMW’s introduction of the Kl in San Antonio, rode the bike for two days and must admit that I was only partly impressed. It seemed too long and heavy for a sportbike, yet lacked the luggage or comfort to make it a good sport-tourer. The reach to the handlebars, even with my long arms, gave me a literal pain in the neck.

Gil’s Kl, however, had set-back blocks to bring the handlebars rearward a couple of inches, which revolutionized its comfort level. Still no luggage, but a tankbag and a rear seatpack carried enough for a solo rider (Skip’s Chevy Suburban carried a little extra luggage for each of us). Also, Gil had installed a 4-into-l header and recalibrated the EFI, so the bike had a wonderful deep growl and perfect, crisp throttle response. It felt solid, fast (150 mph), dead stable and precise. By the end of the day I understood why Gil had never been able to bring himself to trade the Kl in on his new RS; it has a kind of bone-deep composure and a high level of mechanical polish that makes it wear well, hour after hour.

That night, our destination was a restored adobe cattle ranch and private fort called Cibolo Creek Ranch, located four miles off Highway 67 on a dirt road. While other bikes squirmed and wobbled, the heavy, long-wheelbased Kl sliced through the dust and loose gravel like a Coast Guard cutter. A pleasant and unexpected surprise.

Cibolo Creek Ranch was built during the 1850s by pioneer/cattle baron Milton Favor, and was just recently restored by the Texas Historical Commission. The workmanship is exquisite and the care they took to get it right is remarkable. It has fortress walls, moats, stables, a big screened porch, a shaded colonnade along the guest rooms, library, music room and an elegant Spanish-style dining room.

It also has a big outdoor firepit, where we stood around a mesquite blaze at night, warming ourselves and sipping from the agave and mescal family of fine drinks. Skip and I got into a long, complex (or so it seemed to us) discussion in which we explored moral relativism, the internal conflicts of Hogolian ethics and which current dual-purpose bike would be best to buy.

Being one of the four “single” guys on the trip, I was assigned a roommate, and he turned out to be none other

than the upbeat, irrepressible Randy Lewis, retired IndyCar driver and now president of Lewis Vineyards in Napa. A genuine fast guy: Despite never having a really first-rate ride, Lewis had managed to grid himself on the fourth row of the Indy 500 three years running, alongside the likes of Mario Andretti and Al Unser Jr.

The same speed and talent showed itself in his motorcycle riding, and I spent a good part of the trip trying to keep Randy’s disappearing FZR1000 in my distant sights, while not actually killing myself. A recent convert to motorcycling, he rode faster than anyone on the trip and never put a wheel wrong. So much for genetics vs. experience.

The next day was free for local exploration and riding, so I took a solo trip down the Rio Grande toward Big Bend National Park. The river road, Highway 170, between Presidio and Terlingua, turned out to be a landmark piece of motorcycle pavement-tightly twisting, rising and falling through the narrow river gorge of painted rock that’s half badlands and half fantasy. The Kl loved it, growling and wailing, cutting up distance like a well-oiled chainsaw.

I stopped at the mining ghost town of Terlingua, home of the famous annual chili cookoff. The town itself is nothing but a bunch of fallen-down adobe walls, yellow dust and a couple of stores. In the general store I bought myself a “Viva Terlingua” bumper sticker to put on my guitar case back home, in honor of Jerry Jeff Walker. The chili cookoff was less than a week away, and already the nearby arroyos and parks were filled with campfires giving off a heady mixture of wood smoke and simmering Texas red.

It was too late in the day to explore Big Bend Park, so I cut north through Alpine and then headed back through Marfa. I’d hoped to see the old ranch house from Giant, where James Dean, Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, Mercedes McCambridge, et al had once worked their magic, but a gas station attendant told me it had been wind-damaged and then tom down. That grand two-story mansion, he told me, was “nothing but a bunch of boards nailed on telephone poles.”

The next day we crossed the border at Ojinaga after a short delay in which Mexican immigration officials frowned at the mass of paperwork Skip had prepared for each bike, then stamped, notarized, embossed, signed, collated, stapled and blessed each document as if it were the Treaty of Ghent. Young soldiers with automatic weapons looked on.

Funny how there’s always an inverse proportion between the number of official documents and the effectiveness of government. You’d think bureaucrats might notice this embarrassing connection.

Free at last, we rode into Mexico.

Chihuahua!

To Mexicans, the big northern province of Chihuahua is their own Texas, the mythical West of their national imagination. It’s a land of mountains, cattle ranches, fertile valleys greened by precious water and wide-open spaces. Villa’s home turf, where nearly every town was fought over, taken and retaken about a dozen times during the revolution. Bloody ground.

Seems peaceful now, and the ride into the city of Chihuahua was our third day of astoundingly beautiful road, this time cutting through the Rio Conchos valley, over high, windswept mountains and down into a wide basin. Two lanes, good pavement, lots of turns, no traffic. And no cops.

Chihuahua is a clean, busy town with a nice cathedral square, lots of banks, modern hotels and restaurants. We stayed at the Palacio del Sol, right in the center of town, and had a good dinner at a small restaurant called Rincon Mexicana nearby.

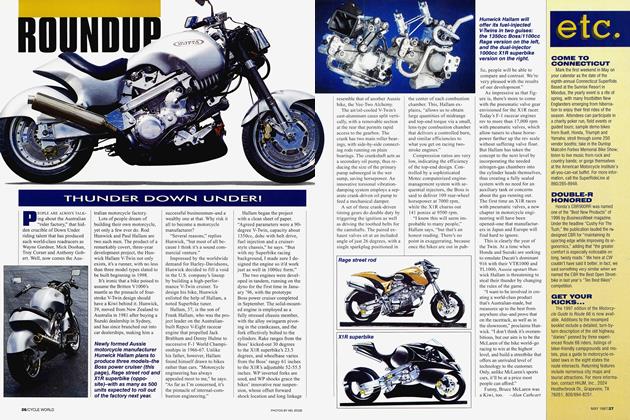

From Chihuahua we headed west through farming and ranch country and began our curving, upward climb into the Sierra Madre toward the old logging village of Creel and Mexico’s famous Copper Canyon National Park. Best riding yet, in a series of great riding days.

For some reason, the name Copper Canyon (Barranca de Cobre) had suggested to me a rather desolate, dry and dusty mining region. Not so. It’s high, rugged country, but green and covered with pine forests, encompassing the largest and deepest canyon system in North America. Deeper than the Grand Canyon, it is over four times as vast. The name Copper comes not from mining, but from the color of the exposed rock. Spectacular country, almost unknown to most Americans.

The Mexicans call this area the Sierra Tarahumara because the almost inaccessible valleys and peaks are home to some 50,000 Tarahumara Indians. A shy, private people renowned for their stamina and swift running ability, they never “surrendered” or entered into any political discourse with the government of Mexico. When pressed or threatened, they just disappeared farther into the hills, thereby missing out on several revolutions, two world wars, the disco craze, both O.J. Simpson trials and the civilizing benefits of network television.

To survive, they hunt and grow small hillside gardens, and also make beautiful baskets and other handicrafts, which they sell at tourist sites along the torturous Chihuahua al Pacifico railroad line.

We stayed at a nice motel in Creel, parked our bikes for a day and then took an overnight trip by bus to the high, cliffside Hotel Mirador. We were supposed to take the train, but a landslide had closed it down for a few days. All along the line, marooned tourists had to accustom themselves to being stuck in one of the most beautiful places on earth, with only Mexican food and margaritas to survive on. Grim stories emerged of people forced to drink their own wine. Which we certainly did.

Our group included no fewer than four California vintners: Gil and Beth Nickel of Far Niente, John Trefethen of Trefethen Vinyards, Ren and Marilyn Harris of Paradigm and Randy Lewis of Lewis Vineyards. Each of them brought a few cases of wine along and packed it in our Suburban chase car-the luggage & winemobile. If Skip had crashed, he would have drowned in cabernet sauvignon.

Fortunately he didn’t, so some of our evenings are lost to history, with no reliable witnesses. I do know that Gil told at least one joke that required him to stand on the table and clutch his ankles, but telling it here would only cause problems.

So we arrived by bus, and the Hotel Mirador turned out to be, like Cibola Creek Ranch, one of the most beautiful lodges I’ve seen. Timber, adobe and tile put together in a superb piece of Southwestern architecture, built into the cliffs on the rim of the canyon.

The average American conception of rural Mexico (well, mine, at least) might scarcely credit such a place existing on the Great Divide of the Mexican Sierra. But this was true of all our hotels; they were as good as-or vastly better than-most places I would stay on a bike trip in the U.S., cheapskate that I am.

My own cost on this trip, incidentally (single, with own bike), was $1289 for eight days of travel, covering hotels and two meals a day. Lunches, gasoline, drinks and air travel to El Paso were on me. As the trip progressed, it seemed like a bargain.

After Copper Canyon, the trip back to El Paso felt like a downhill run toward home, but it was good riding all the way. Well, except for the border crossing. After a night at another good hotel in Casas Grandes, we crossed back into the U.S. at Palomas, which has a main street of hippo-sized ski moguls fashioned in mud. A hydrant had burst and the whole downtown was a giant mudhole.

As we slithered and bobbed up to a stoplight, I raised my faceshield and said to Gil, “This town is a disgrace! Don’t they have a mayor they can run out of office?”

But we were back at the border, and border towns have ever been transient places where normal rules do not always apply, where cultures mb up against each other, generating frictional smoke and showing off their worst traits. Mexico can’t control its birth rate, which always outstrips its resources, and the U.S. can’t control its appetite for cheap goods-as if there could ever be such a thing-and the border towns are a product of those two facts. Improvidence meets avarice. There’s a sense that no one is in charge.

This time we were waved across the border without even being stopped. We had lunch in the town of Columbus, where Pancho Villa either had or had not made his historic, ill-advised raid on the U.S. The fast ride back to El Paso on the border road would have been unremarkable except that Ken blew a rear tire on his GS BMW and managed to ride out the worst high-speed tankslapper I’ve ever seen. He calmly replaced his tube on the roadside with simple tools and we were on our way.

Back in El Paso, we loaded our bikes at an airport cargo dock, while across the mnway Air Force One sat on the ramp. President Clinton was in town, making one of his last speeches of the 1996 presidential campaign. The bell-hop at our hotel told me most of the Hilton had been filled with Secret Service agents for the whole week before Clinton’s short visit, screening El Paso for the usual bad actors and dim bulbs.

Say what you will about any president, the courage to dive into crowds over and over again is almost beyond comprehension in the secure lives most of us lead. You could feel

the tension in El Paso, and it hung in the hotel like a leftover ringing in the ears when a fire alarm has been turned off.

Curiously, our Napa Valley Touring Society trip through the Ozarks had taken us through election night four years earlier, when Clinton was in nearby Little Rock, awaiting the results. When Clinton runs, we ride.

After a big steak dinner at the famous Billy Crew’s Steak House, during which I accidentally ordered a T-bone about the size and thickness of a window air-conditioning unit, we had many toasts and said our goodbyes. In the morning we all flew home our separate ways.

Before my own flight, I had breakfast with Skip and Ken. Over coffee, I confessed that I hadn’t known what kind of bike would be best for Mexico. Dual-purpose? Pure dirt? Touring? Yet this trip had covered some of the best sportbike roads I’d ever ridden.

Skip smiled and nodded, “We do 18 rides a year down here, all over Mexico, and almost any bike works. But many people think the pavement ends at the border, and they’re afraid to come down here. ‘What about banditos?’ is another question we hear all the time. Half of our job is simply to dispense with anxieties. We do this mostly by taking care of the paperwork at the border crossing, and after that giving people some history and a feel for the place.

“Mexico is a remarkable country to tour,” he added. “Three hundred miles from an American shopping mall, you can ride curving mountain roads through country populated by primitive Indians in loincloths. And mile for mile, dollar for dollar, these roads can match anything in the world. Once people discover this, they keep coming back. They want to go deeper into the country and see more of it.”

He had that right, at least in my case.

When I got home, the driveway was drifted with snow and the right front tire on my snow-blower was flat. Also, the garage door was frozen to the concrete floor and had to be broken loose with a crowbar. No big deal, really. I’ve learned to live with seasonal darkness and cold.

But without Mexico, I’d go crazy. □