Real versus toy bikes

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

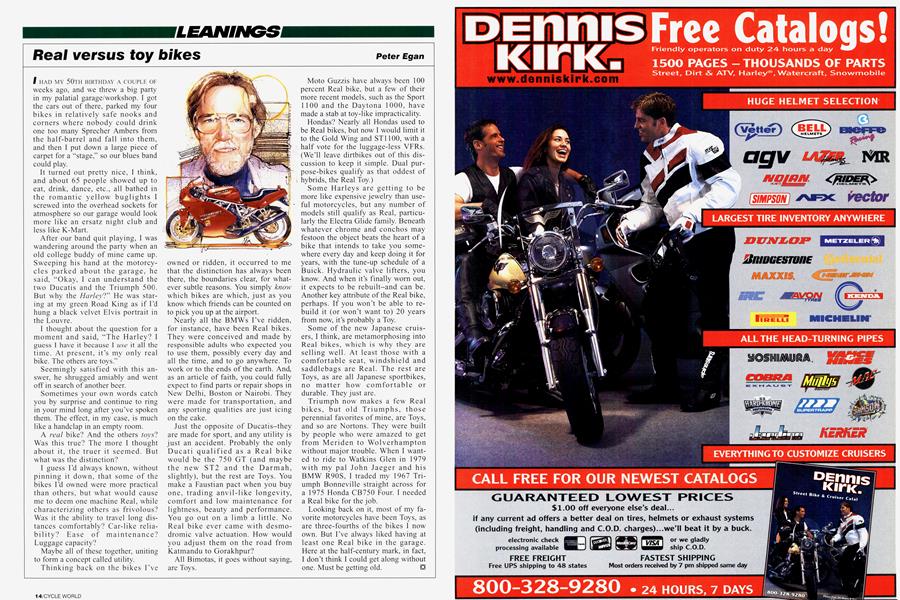

I HAD MY 50TH BIRTHDAY A COUPLE OF weeks ago, and we threw a big party in my palatial garage/workshop. I got the cars out of there, parked my four bikes in relatively safe nooks and corners where nobody could drink one too many Sprecher Ambers from the half-barrel and fall into them, and then I put down a large piece of carpet for a "stage," so our blues band could play.

It turned out pretty nice, I think, and about 65 people showed up to eat, drink, dance, etc., all bathed in the romantic yellow buglights I screwed into the overhead sockets for atmosphere so our garage would look more like an ersatz night club and less like K-Mart.

After our band quit playing, I was wandering around the party when an old college buddy of mine came up. Sweeping his hand at the motorcy cles parked about the garage, he said, "Okay, I can understand the two Ducatis and the Triumph 500. But why the Harley?" He was star ing at my green Road King as if I'd hung a black velvet Elvis portrait in the Louvre. -

I thought about the question for a moment and said, "The Harley? I guess I have it because I use it all the time. At present, it's my only real bike. The others are toys."

Seemingly satisfied with this an swer, he shrugged amiably and went off in search of another beer.

Sometimes your own words catch you by surprise and continue to ring in your mind long after you've spoken them. The effect, in my case, is much like a handclap in an empty room.

A real bike? And the others toys? Was this true? The more I thought about it, the truer it seemed. But what was the distinction?

I guess I'd always known, without pinning it down, that some of the bikes I'd owned were more practical than others, but what would cause me to deem one machine Real, while characterizing others as frivolous? Was it the ability to travel long dis tances comfortably? Car-like relia bility? Ease of maintenance? Luggage capacity?

Maybe all of these together, uniting to form a concept called utility. Thinking back on the bikes I've owned or ridden, it occurred to me that the distinction has always been there, the boundaries clear, for what ever subtle reasons. You simply know which bikes are which, just as you know which friends can be counted on to pick you up at the airport.

Nearly all the BMWs I've ridden, for instance, have been Real bikes. They were conceived and made by responsible adults who expected you to use them, possibly every day and all the time, and to go anywhere. To work or to the ends of the earth. And, as an article of faith, you could fully expect to find parts or repair shops in New Delhi, Boston or Nairobi. They were made for transportation, and any sporting qualities are just icing on the cake.

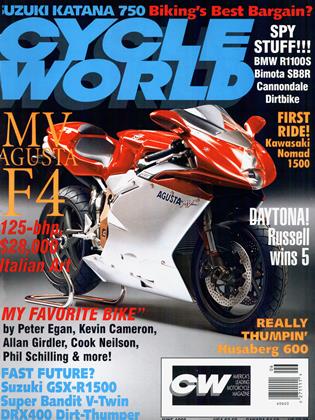

Just the opposite of Ducatis-they are made for sport, and any utility is just an accident. Probably the only Ducati qualified as a Real bike would be the 750 GT (and maybe the new ST2 and the Darmah, slightly), but the rest are Toys. You make a Faustian pact when you buy one, trading anvil-like longevity, comfort and low maintenance for lightness, beauty and performance. You go out on a limb a little. No Real bike ever came with desmo dromic valve actuation. How would you adjust them on the road from Katmandu to Gorakhpur?

All Bimotas, it goes without saying, are Toys.

Moto Guzzis have always been 100 percent Real bike, but a few of their more recent models, such as the Sport 1100 and the Daytona 1000, have made a stab at toy-like impracticality. Hondas? Nearly all Hondas used to be Real bikes, but now I would limit it to the Gold Wing and ST1 100, with a half vote for the luggage-less VFRs. (We'll leave dirtbikes out of this dis cussion to keep it simple. Dual pur pose-bikes qualify as that oddest of hybrids, the Real Toy.)

Some Harleys are getting to be more like expensive jewelry than use ful motorcycles, but any number of models still qualify as Real, particu larly the Electra Glide family. Beneath whatever chrome and conchos may festoon the object beats the heart of a bike that intends to take you some where every day and keep doing it for years, with the tune-up schedule of a Buick. Hydraulic valve lifters, you know. And when it's finally worn out, it expects to be rebuilt-and can be. Another key attribute of the Real bike, perhaps. If you won't be able to re build it (or won't want to) 20 years from now, it's probably a Toy.

Some of the new Japanese cruis ers, I think, are metamorphosing into Real bikes, which is why they are selling well. At least those with a comfortable seat, windshield and saddlebags are Real. The rest are Toys, as are all Japanese sportbikes, no matter how comfortable or durable. They just are. Triumph now makes a few Real

bikes, but old Triumphs, those perennial favorites of mine, are Toys, and so are Nortons. They were built by people who were amazed to get from Meriden to Wolverhampton without major trouble. When I want ed to ride to Watkins Glen in 1979 with my pal John Jaeger and his BMW R9OS, I traded my 1967 Tri umph Bonneville straight across for a 1975 Honda CB750 Four. I needed a Real bike for the job.

Looking back on it, most of my fa vorite motorcycles have been Toys, as are three-fourths of the bikes I now own. But I've always liked having at least one Real bike in the garage. Here at the half-century mark, in fact, I don't think I could get along without one. Must be getting old.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue