Siberian Sojourn

Embracing Mother Russia, and then some

WENDY F. BLACK

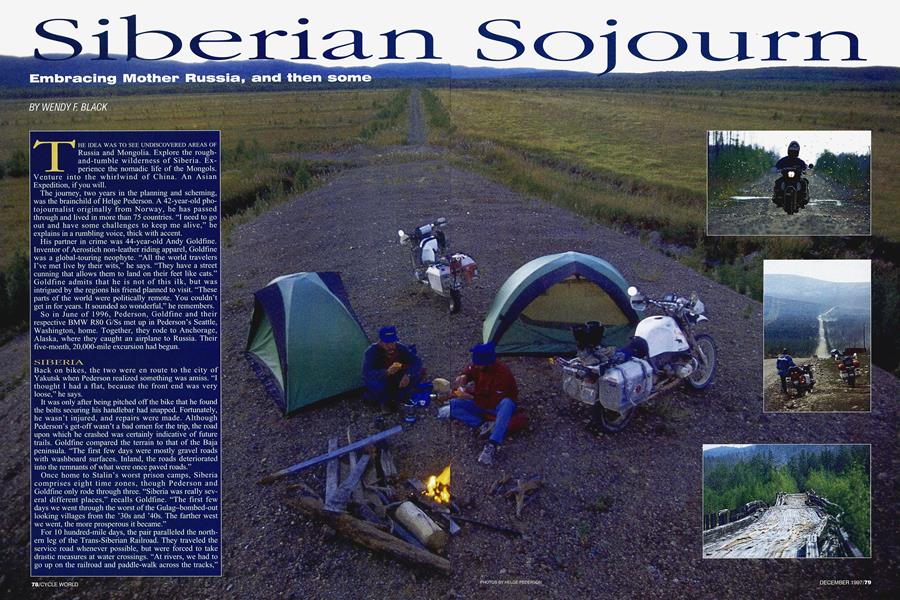

THE IDEA WAS TO SEE UNDISCOVERED AREAS OF Russia and Mongolia. Explore the rough-and-tumble wilderness of Siberia. Experience the nomadic life of the Mongols. Venture into the whirlwind of China. An Asian Expedition, if you will.

The journey, two years in the planning and scheming, was the brainchild of Helge Pederson. A 42-year-old photojournalist originally from Norway, he has passed through and lived in more than 75 countries. “I need to go out and have some challenges to keep me alive,” he explains in a rumbling voice, thick with accent.

His partner in crime was 44-year-old Andy Goldfine. Inventor of Aerostich non-leather riding apparel, Goldfine was a global-touring neophyte. “All the world travelers I’ve met live by their wits,” he says. “They have a street cunning that allows them to land on their feet like cats.” Goldfine admits that he is not of this ilk, but was intrigued by the regions his friend planned to visit. “These parts of the world were politically remote. You couldn’t get in for years. It sounded so wonderful,” he remembers.

So in June of 1996, Pederson, Goldfine and their respective BMW R80 G/Ss met up in Pederson’s Seattle, Washington, home. Together, they rode to Anchorage, Alaska, where they caught an airplane to Russia. Their five-month, 20,000-mile excursion had begun.

SIBERIA

Back on bikes, the two were en route to the city of Yakutsk when Pederson realized something was amiss. “I thought I had a flat, because the front end was very loose,” he says.

It was only after being pitched off the bike that he found the bolts securing his handlebar had snapped. Fortunately, he wasn’t injured, and repairs were made. Although Pederson’s get-off wasn’t a bad omen for the trip, the road upon which he crashed was certainly indicative of future trails. Goldfine compared the terrain to that of the Baja peninsula. “The first few days were mostly gravel roads with washboard surfaces. Inland, the roads deteriorated into the remnants of what were once paved roads.”

Once home to Stalin’s worst prison camps, Siberia comprises eight time zones, though Pederson and Goldfine only rode through three. “Siberia was really several different places,” recalls Goldfine. “The first few days we went through the worst of the Gulag-bombed-out looking villages from the ’30s and ’40s. The farther west we went, the more prosperous it became.”

For 10 hundred-mile days, the pair paralleled the northern leg of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. They traveled the service road whenever possible, but were forced to take drastic measures at water crossings. “At rivers, we had to go up on the railroad and paddle-walk across the tracks,” explains Goldfine. “Very frightening.”

The bridges, upon which a train could come ’round at any moment, were often located on blind turns and were lengthy enough to require 20-minute crossings. “There were no real close calls,” Pederson says, then adds, “but it was mentally scary.”

At dusk, the duo set up camp along the service road, and spent several nights on the shores of Lake Baikal, the largest-volume fresh-water lake in the world. “We camped most of the time because we had no other choice,” explains Pederson.

When confronted with Siberian hospitality, however, both travelers were happy to comply. “People were very accommodating when we came upon them,” he continues. “We were tired, but they saw an opportunity for party time. They like to drink vodka.”

Goldfine was so taken with the natives that he has kept in touch with a few since returning home to Duluth, Minnesota. “Siberia was cool, and the people were so wonderful,” he says.

MONGOLIA

Settled into a railroad boxcar that they’d secured for $13, Pederson and Goldfine crossed the Siberian border into Mongolia with minor hassles. They emerged from the train to discover how much this country differed from the one they’d just exited.

“In Siberia, the land was rocky, rugged, swampy, brushy, forested,” describes Goldfine. “Mongolia was all hard dirt and grassland. There were 20 or 30 million grazing animals and only a few million people.”

Pederson called it “the world’s largest golf course.”

The pair headed first for Ulan Bator, Mongolia’s largest city, which they had earlier designated as a supply point. Because of the mechanical toll Siberia's harsh terrain had taken on their BMWs, they faxed the U.S. with requests. Their care package was waiting and held the needed parts, including new tires and a special treat: ajar of peanut butter. Despite the apparent civilization of Ulan Bator, which boasts a population of about 100,000, most Mongols reside in tents. "They are still a nomadic people and were so far back in time that I imagined myself a Viking version of Genghis Khan," laughed Pederson.

Their route through this undeveloped land was a large ioop that included the Gobi Desert. Luckily, their trip took place during the rainy season, so the famous wasteland was actual ly lush and green. "And very muddy," says Pederson. "If we hadn't gotten our new knobbies, it would have been bad." To navigate such wilderness, Pederson and Goldfine used Global Positioning Systems and military topographical maps. Upon entering the country, they had also been assigned a guide. Preferring to go it alone, however, they convinced the guide to allow them to travel sans assistance. They then made plans to hook up at the end of the journey. Later, they discovered that had anything untoward happened to them, the guide would have gone to jail.

Such rigid governmental standards seem harsh and archa ic, but visiting Mongolia was worth every hardship. Summed up Goldfine, "Riding through Mongolia was like riding through the Bible."

CHINA

It was in China, however, that they came to realize what a strict regime really is. Pederson was intent upon getting a photograph of themselves with their BMWs in Tiananmen Square, where a number of protesting students had been killed in 1989. So at 5 a.m., the two gathered their belongings and sneaked out of their hotel room. They rode to the entrance of the Forbidden City, where they cajoled a local official to take their picture.

“Fie only did it to get us out of there,” maintains Pederson. “It was a little exciting. If the guards had caught us, they probably would have taken our bikes and kicked us out of the country.”

By this time, such authoritarian shenanigans were old hat. For example, the duo’s original route was through Manchuria; at least until the government intervened. The strongly suggested alternative was a longer course that wound through more cities than countryside. And, their Chinese guide was not as easily swayed as his Mongolian counterpart. “We had to have a guide in China, and we could never get him to relax,” says Pederson.

“But sometimes we ‘accidentally’ lost him. Those were the best times.”

With the guide conveniently absent, the pair clandestinely toured Chinese farmland, where even in the most remote areas, they were surrounded by villagers whenever they stopped. “Every square inch of this country has people on it,” proclaimed Goldfine.

The cities were even more crowded, and battling the traffic was, in Pederson’s words, ridiculous. Goldfine puts forth his 2 cents: “There was so much going on in China compared to Mongolia and Siberia. There would be a Mercedes 500 SEL going 100 mph on the same road as ox carts.”

On just such a highway, Goldfine got himself into a bit of bother trying to pass a car that didn’t want to be passed. Eventually, he had enough. In a fit of testosterone-induced dragracing, Goldfine over-revved the engine and bent two valves. “I was running on adrenaline and I was harassing the driver,” he admits sheepishly.

The nearest BMW shop being half a continent away, Goldfine rounded up some Toyota valves which could be ground down to fit the BMW. He took them to a local motorcycle factory where they were installed for $300. Total downtime: two days.

All together, this was par for the Chinese course. Says Goldfine, “China was a lot of fun, but it was a lot of work. We were both relieved to get out.”

HOMEWARD-BOUND

After a rest stop in Japan, the two men went their separate ways: Goldfine flew back to Minnesota; Pederson hopped a ship that deposited him in Los Angeles. From there, he climbed aboard his BMW and rode to Seattle.

Reflecting on their trip almost a year later, these two very different men espouse suspiciously similar opinions. “This was the most fun thing I have ever done,” Goldfine states unequivocally. Then he adds, “But I don’t think I’m as good a traveler as Helge.”

Pederson diplomatically concurs: “We found out we are very different. Andy is a businessman who likes a little more comfort. I like to be dirty for weeks.”

Both agreed that although the excursion wasn’t always smooth-running, their individual traits complemented one another’s in the end. “We worked very well together,” says Goldfine. “I was very comfortable following him around because this was his world. He’s very much in love with his life.”

Today, Goldfine is back in Duluth, manufacturing Aerostich gear and selling it to the likes of you and me (not to mention Harrison Ford and Lyle Lovett). And Pederson? Hard to say. Last we heard, he was incommunicado, touring somewhere in South America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue