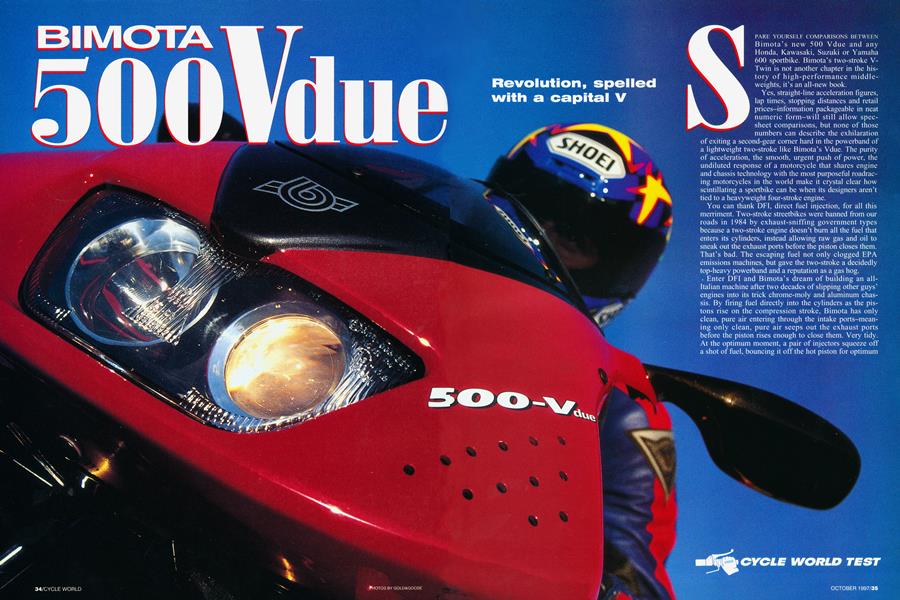

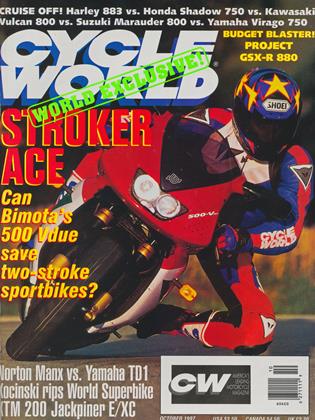

BIMOTA 500 Vdue

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Revolution, spelled with a capital V

SPARE YOURSELF COMPARISONS BETWEEN Bimota's new 500 Vdue and any Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki or Yamaha 600 sportbike. Bimota's two-stroke V-Twin is not another chapter in the history of high-performance middle-weights, it's an all-new book.

Yes, straight-line acceleration figures, lap times, stopping distances and retail prices-information packageable in neat numeric form-will still allow specsheet comparisons, but none of those numbers can describe the exhilaration of exiting a second-gear corner hard in the powerband of a lightweight two-stroke like Bimota's Vdue. The purity of acceleration, the smooth, urgent push of power, the undiluted response of a motorcycle that shares engine and chassis technology with the most purposeful roadrac ing motorcycles in the world make it crystal clear how scintillating a sportbike can be when its designers aren't tied to a heavyweight four-stroke engine.

You can thank DFI, direct fuel injection, for all this merriment. Two-stroke streetbikes were banned from our roads in 1984 by exhaust-sniffing government types because a two-stroke engine doesn't burn all the fuel that enters its cylinders, instead allowing raw gas and oil to sneak out the exhaust ports before the piston closes them. That's bad. The escaping fuel not only clogged EPA emissions machines, but gave the two-stroke a decidedly top-heavy powerband and a reputation as a gas hog.

Enter DFI and Birnota's dream of building an all Italian machine after two decades of slipping other guys' engines into its trick chrorne-moly and aluminum chas sis. By firing fuel directly into the cylinders as the pis tons rise on the compression stroke, Bimota has only clean, pure air entering through the intake ports-mean ing only clean, pure air seeps out the exhaust ports before the piston rises enough to close them. Very tidy. At the optimum moment, a pair of injectors squeeze off a shot of fuel, bouncing it off the hot piston for optimum

atomization. Boom-compression and clean emissions, improved midrange and respectable fuel economy. A miracle? Well, sportbike nuts think so.

During our visit to Bimota’s three-story Rimini factory, we found every nook and cranny stuffed with Vdue rolling chassis-tucked along hallways, parked tightly near the dyno, jammed into the final assembly area-all waiting for engines that were overdue from Morini. Bimota teamed with Morini after interviewing a variety of potential engine builders, and faith in the Bologna-based company has proved worthwhile because the Morini-built engine is powerful, technologically advanced and tough-just a little late.

Chief engineer Pierluigi Marconi and his team were using the downtime to reprogram the fuel injection to work with Siemens injectors, a major switch from the Weber-Marelli injectors the project began with and another battle in the team’s toughest challenge: getting the “carburetion” right. A central control unit reads a variety of data to control fuel delivery, aspects such as throttle .position, rpm, water temperature, road speed, airbox pressure, all helping the electronic brain achieve stoichiometric fuel delivery at engine speeds from idle to the 10,000-rpm redline. Sophisticated electronics have helped with this challenge, and the factory was more than happy to sit Cycle World in the seat of the company’s first pre-production Vdue (pronounce it like the Italians: “Vee-doo-ay”) and point us out the door.

Our pre-production model had been bolted together on the assembly line with production parts, but wore Weber injectors. The chassis, suspension, engine, gearing, bodywork and other sundry parts were production pieces, with only the electronics and injectors due for upgrading. The prototype Vdue that Euro-correspondent Alan Cathcart rode (see Roundup, September) sat covered in grime, having just returned from a day of riding in the rain with a laptop computer mounted on the fuel tank for on-the-fly jetting adjustments. The differences between the two bikes display Bimota’s fast-paced development, and our time at the factory examining the production process and assembly techniques left us with the overwhelming feeling that Bimota is doing this bike right. From the initial quality inspection of every component to the running of each bike on the dyno, Bimota stresses quality control, and has recently completed major upgrades to qualify for ISO9001, an international standard of production that stresses quality.

The Bimota’s starter motor doesn’t get much of a workout because the V-Twin fires immediately, hot or cold. Electronics handle the enrichening circuit automatically, so there’s no choke knob to fiddle with. The artistic seat pad feels immediately-and surprisingly-comfortable, and remains that way, though it’s a tall 32.2 inches off the ground. The overall seating position is decidedly sporting, mirroring the Ducati 916’s ergonomics, with a slightly shorter reach to the bars and slightly less legroom. Taller riders won’t feel cramped until they try to tuck in behind the bubble; there’s not enough room on the svelte solo seat to slide your butt back for that Mick Doohan impression, though our tester’s sub-6-foot frame fit just about perfectly.

If you’ve heard a TZ250 racebike run, then you have a good idea of the Bimota’s unique sound, though it barks in a deeper voice than the Yamaha V-Twin. The expansion chambers run under the seat to a primary set of mufflers, then somewhat awkwardly out the right side to a pair of carbon-fiberclad canisters. There’s no catalytic converter, because the DFI system is so clean. But is the bike quiet enough for the governments of the world? According to Bimota it is, though the onslaught of sound from the exhausts and dry clutch must be right on the limit of permissible noise.

Plonking along in Rimini’s stopand-speed traffic points out the progress Bimota has made with the fuel delivery. Cathcart’s report on the prototype indicated the bike’s inability to cruise at partial throttle settings without bucking and surging, making around-town riding difficult and uncomfortable. Our pre-pro model delivered fuel more smoothly at small throttle openings, though it displayed a dead spot in the fuel-delivery curve at 4500 rpm. If you’re stepping off a perfectly carbureted YZF600, say,

the Vdue will take some acclimation. If you’ve grown up on radical project bikes or a Formula 2 racer of your own, this carburetion glitch will pass as a minor annoyance. Of course, it’s the YZF rider that Bimota hopes to snare, so you can be sure the low-speed driveability is a problem Bimota wants to eradicate before the assembly line rolls.

This engine began life as a racing motor, so low-speed carburetion was simply not an issue-upper midrange and top-end steam were all that mattered. In other words, big thrills wait between 7000 and 10,000 rpm, though Bimota’s efforts have made the Vdue surprisingly tractable at any point on the tachometer. You won’t mistake it for a V-Max at 4000 rpm, but power delivery anywhere above idle is certainly acceptable, and a large step ahead of yesteryear’s peaky two-strokes due to the improved use of fuel at low rpm. Still, this engine wants and needs to be revved.

Bimota’s twin-crank 90-degree V-Twin becomes eerily smooth as the revs rise, and quickly addicts the rider to high-rpm throttle twisting. That addiction can be a whole lot of fun, especially on the kinds of roads we sampled near Rimini that had us flashing through second-gear comers and wheelying up adjoining straights while freelance photographer David Goldman snapped away. There’s a noticeable step in power as the tach clears 7000 rpm, the point at which the electronic powervalves in the exhaust ports take effect,

followed by a clean, smooth, ripping pull to redline.

And then the Vdue surprises you with something totally unexpected: a rev-limiter.

A rev-limiter? On a two-stroke? Two-stroke riders know when it’s time to shift because the power goes soft; with no cams or valves whirling around to mechanically limit rpm, a rev-limiter has never been a needed part of a two-stroke’s makeup. But consider that a two-stroke makes power with every stroke of the piston, and you’ll begin to understand the challenge Bimota faces in injecting fuel above 10,000

rpm-what would be 20,000 rpm on a four-stroke. With the

current DFI, the fuel mixture gets precariously lean above 10 grand as the Weber system fails to keep up with the incoming charge. The engineers hope to raise the rev-limiter with the use of Siemens injectors.

Bimota equipped the Vdue

with a good-shifting, cassette-type, six-speed transmission that has moderately spaced ratios and a surprisingly tall 16/39 sprocket choice. The factory wants to keep riders from wheelying over backward under hard first-gear accel

eration, but the tall gearing choice, when combined with the hazy partial-throttle “carburetion,” made initial stop-sign leaves tricky until we learned to trust the grunt of the engine and simply release the clutch and ride away. At freeway speeds, the engine doesn’t have much oomph because it’s only turning 3100 rpm at an indicated 100 kph (62 mph), so you learn to dance on the gearshifter prior to a quick pass.

The cassette tranny hints that alternate ratios may soon be available, and we’d opt to leave first gear in place and tighten up the next five ratios, a la the close-ratio box in a Honda RC30, for example.

Two-stroke riders learn to use the brakes to full effect because there’s little engine-braking to help slow the bike. Bimota made the job easy by fitting Brembo calipers on all three rotors. The Italian calipers and rotors offer outstanding power and a wonderfully linear feel that makes goofy fun like nose-wheelies tempting at every stop. The rear caliper needs to be copied by all Japanese sportbike makers because it takes a heavy stomp to lock, and offers useful linearity-at least until the rear wheel is off the ground. And with the Vdue’s 52.4-inch wheelbase, that happens quite frequently.

The front Brembos bolt to an exceedingly well-sorted Paioli fork with massive 46mm stanchions bolted into trademark billet Bimota triple-clamps that have inspired every motorcycle machinist since 1978. The triple-clamps augment Bimota’s oval-shaped aluminum-tube frame, TIGwelded to billet pivot plates that hold the asymmetric aluminum swingarm. The chassis is gorgeous, strong, light, short, compact and has a relatively easy job of holding the featherweight V-Twin as a stressed member.

Production Bimotas will be fitted with an Öhlins or Paioli

rear damper that offers three-way adjustability (like the Paioli fork), plus ride-height adjustment. Our testbike wore an Öhlins shock; we ran 70 percent of the available preload and found the spring rate, through the non-progressive linkage, too soft as the pace was upped. Static-sag numbers confirmed our seat-of-the-pants feel, and Bimota admitted to choosing this spring for comfort and ride characteristics. Those looking to firm up the ride can replace the spring easily enough.

Despite the too-soft shock spring, the Vdue offers handling precision that isn’t available on any current production motorcycle in the U.S. Little effort is needed at the clip-ons to change direction, which isn’t too surprising considering the bike’s claimed 374-pound wet weight, but few of us have ever experienced the real-world attributes of a bike this light. You find yourself running cornering lines that were previously unavailable, carving through a double-apex sweeper with two distinct apexes, not just the broad swathe of cornering you’re experiencing now. If you want to place the 500 at the outside edge of the road while entering a left-hand comer, you can choose which part of the front tire touches the white line. Inches, not feet, become your measuring stick, and as you adapt to the bike’s sky-high abilities, you gain a real glimpse into why GP two-strokes rule roadracing.

The Vdue rider’s initial impression is an overwhelming feeling of manic immediacy. But this immediacy is backstopped by an inherent stability that Bimota creates by juggling rake and trail figures and triple-clamp offset. We couldn’t find a road or speed at which the Vdue shook its head, wobbled, flexed or misbehaved in any way. And we tried hard. As initial impression grows into acclimation, you find yourself on a stable platform that’s willing to go straight over any pavement imperfections, yet responds accurately and immediately to direction and speed changes. It sounds too good to be true, but that’s because you haven’t ridden a sub-400-pound streetbike that makes a claimed 101 horsepower. Removing weight doesn’t just affect acceleration and braking, it touches every facet of a sportbike’s repertoire and instantly improves the fun factor. Additionally, Bimota’s tiny V-Twin is mounted low and forward in the frame and carries the majority of its weight near the crankcase center line, as opposed to a four-stroke that carries significant weight high in the cylinder head. It makes a difference, and you can’t read that on a spec sheet.

Our pre-production experience in Rimini left us with an excitement for the future that no four-stroke middleweighti

could have provided. Those looking for a refined and seamless backroad tool should look elsewhere, because Bimota’s 500-in pre-production form at least-more closely resembles a project bike or racing machine that provides the undiluted pleasures of high-performance riding at the expense of allaround ridability. Work on partial-throttle fuel delivery and extending the bike’s usable redline will continue as the Siemens injectors become part of the package, and we must stress that Bimota has taken giant strides in this area since the prototype Vdue.

If driveability glitches and an artificially low redline are the costs of an emissions-legal two-stroke, many will gladly pay. Bimota again leads the charge into the production-bike future, as it did with perimeter frames and swingarm front suspensions. It’s a whole new book, and Bimota is writing a terrific first chapter. □

BIMOTA

500 VDUE

$20,275

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontPlan 2003

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997