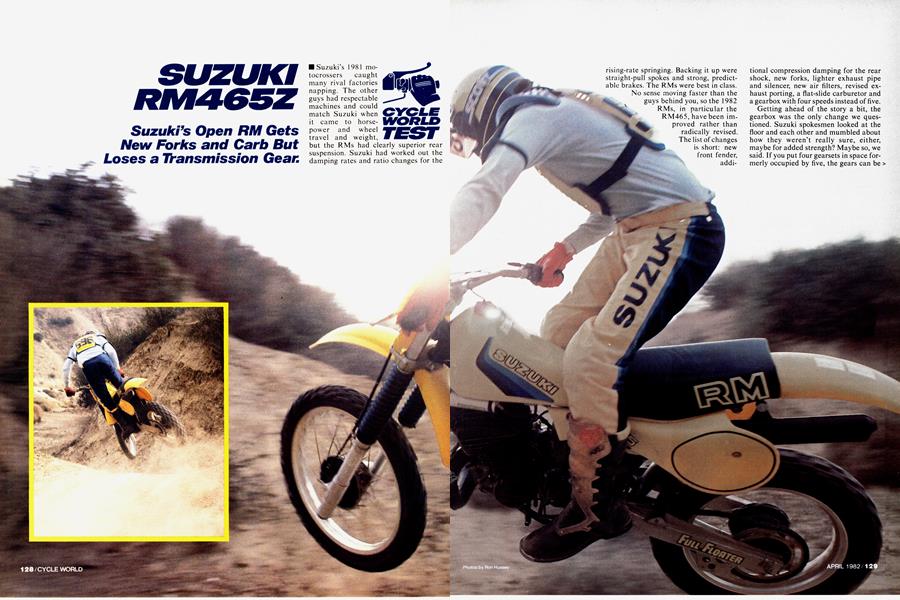

SUZUKI RM465Z

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Suzuki's Open RM Gets New Forks and Carb But Loses a Transmission Gear.

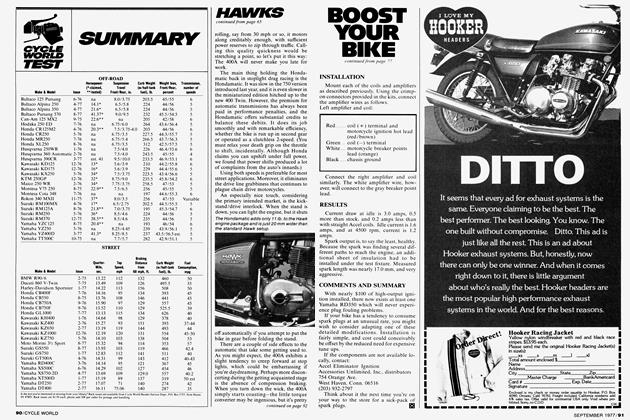

Suzuki's 1981 motocrossers caught many rival factories napping. The other guys had respectable machines and could match Suzuki when it came to horsepower and wheel travel and weight, but the RMs had clearly superior rear suspension. Suzuki had worked out the damping rates and ratio changes for the rising-rate springing. Backing it up were straight-pull spokes and strong, predict able brakes. The RMs were best in class. No sense moving faster than the guys behind you, so the 1982 RMs, in particular the RM465, have been im proved rather than radically revised. The list of changes is short: new front fender, addi

tional compression damping for the rear shock, new forks, lighter exhaust pipe and silencer, new air filters, revised ex haust porting, a flat-slide carburetor and a gearbox with four speeds instead of five. Getting ahead of the story a bit, the gearbox was the only change we ques tioned. Suzuki spokesmen looked at the floor and each other and mumbled about how they weren't really sure, either, maybe for added strength? Maybe so, we said. If you put four gearsets in space for merly occupied by five, the gears can be bigger and in theory stronger. While this was being done, we noticed, the engineers increased the diameter of the output shaft, the one that carries the countershaft sprocket. Some really hard riders reported shearing the output shaft where it exits the cases on the five-speed RM465s. The larger output shaft should end that problem. And the wider internal gears should increase strength.

Suzuki didn’t just lop one gear off the end of the transmission. The four-speed box has wider spaced ratios providing nearly the same spread of gear ratios as the five-speed. For comparison, the fivespeed had a 1st gear of 16.69:1 and a 5th of 7.25:1. The four-speed has a 1st of 16:1 and a 4th of 7.63:1. The range of ratios is just slightly narrower than that of the five-speed and is very similar to the ratios Honda uses in its four-speed.

The porting change consists of raising the exhaust port 0.5mm. That doesn’t sound like much and it isn’t much. The higher port has the effect of advancing the time the exhaust opens. Due to the complexities and interlocking relationships of intake and exhaust and all the various pulses in a racing two-stroke, the earlier exhaust lets the engine rev higher. You get more revs and subtract some power from the bottom of the range, which is no worry with the 465.

The higher port also means compression begins later because the piston doesn’t close the port until the piston is higher in the barrel. Two-strokes usually compute compression ratio from the time the cylinder is sealed, while four-strokes measure from the bottom of the stroke and ignore valve timing’s effect.

What all this means for the 465 is that the nominal compression ratio is reduced, from 6.4:1 to 6.1:1, and actual compression is reduced. This results in a small loss of torque, again no problem for the 465, and makes for more controllable power delivery and greater tolerance for poor gasoline.

The cylinder head, barrel, piston, connecting rod and bearings are unchanged but flywheel counterweights are 7 percent heavier. The weight increase is the result of moving the balance holes and making them smaller in diameter. Clutch and clutch hub are unchanged. The primary drive gear is 1mm wider at the boss where the crank drives it.

Changes to the outside of the engine start with the flat-slide Mikuni carb. The carb looks like a combination of Lectron and Mikuni. Removing the float cover reveals normal Mikuni components. Pulling the slide uncovers a normal Mikunitype needle with five-clip adjustment as per past Mikuni practice. The slide return spring is an in-between size that’s larger than Lectrons, smaller than a regular Mikuni round slide.

Flat slide carbs have been around for some time and the factory Suzukis have used them for several years. Flat-slide designs claim many advantages over the round types. But the biggest advantage is airflow across the top of the needle jet. A round slide directs air to the side of the carb opening, a flat slide lets air pass straight through. As a result, Suzuki claims a 50 percent increase in vacuum at the needle jet from quarter to three-quarter throttle openings. So what does this mean to the rider? Better throttle response and increased fuel efficiency due to better mixing of gasoline and air.

Another new part that might be hard to spot is the intake tube. Its inside diameter is increased from 39 to 41mm. Although the carb is still 38mm, the larger tube size lets mixture pass with less restriction, for another small increase in performance.

Although the pipe and silencer have new part numbers they have the same working measurements: that is, the cones and lengths and diameters are the same. The difference is in metal thickness; for weight reduction the ’82 parts are made of thinner metal.

Last year’s airbox with a dual foam filter on each side of the machine is still used. The coarse outside filter is new however. The primary outside filter is thicker, 10mm compared with 15mm for ’82 and it measures 5mm larger in diameter. The increase in thickness and diameter means it seals dirt out better. Suzuki’s excellent owners manual also recommends greasing the edges of the outside filter this year.

Suspension is improved at the rear and new at the front. The forks are still made by KYB but for ’82 have new valving and the sliders are aluminum tubes instead of aluminum castings. The extruded tubes are lighter and stronger. Axle clamps are castings that are press-fit to the tubes. The new units retain 43mm stanchion tubes. The new units have damping that all riders liked.

The ultra smooth rear suspension looks unchanged but the compression damping has been increased by 25 percent over last year’s bike. Compression damping isn’t adjustable but rebound damping is.

A wheel at the top of the shock easily adjusts rebound damping to any of four positions. No changes were necessary as the stock No. 2 position suited all of our testers, but the adjustment is there if needed. Spring preload is also adjustable on the aluminum-bodied shock. The shock body is threaded and the preload changed by turning a ring at the bottom of the shock. The adjustment is rather hard to reach without an optional Suzuki tool but can be done with a long drift punch if necessary. The shock body has a spring preload gauge in its side to make > adjustments more accurate.

The rear shock’s remote reservoir is still placed above the cylinder. This is the wrong place for a reservoir as engine heat can easily reach it, and the aluminum brackets sometimes break. We moved ours to the right rear frame downtube and held it in place with a couple of hose clamps. All of the factory works Suzukis have the shock reservoir placed back by the shock, not over the engine. The reservoir is rather small by modern standards also but none of our riders, including our pros, reported any shock fade.

Plastic parts on the RM are a combination of old and new, but mostly old. The tank, rear fender and side numberplates are unchanged, and the side plates still have too many loose parts when they are removed. Two flathead screws per side and a loose spacer per screw, all different lengths, are used. There must be an easier way. The front fender is a new shape. It is a strange combination of rounded and flat shapes. It looks a little funny but does a satisfactory job of keeping mud off the rider.

Many controls are finally new for ’82. The long outdated, too-short Suzuki throttle that’s been standard since 1975 has finally been replaced with a straightpull design. It works well and has the right length throttle barrel that fits adult hands. Another long overdue item, a folding shift lever, is also stock. Ditto the hand levers; they are new designs with a dog-leg shape. And they are really different. The bottom sides are hollow including the ball ends. Even the control cables have been updated. They’re still not as good as those used on Yamahas and Hondas, but they are usable.

The 1982 frame is virtually identical to the ’81. It’s chrome-moly steel, it’s light and it’s strong. Some of the dimensions, like the 29.5° steering rake and the 58 in. wheelbase are unusual, i.e. less steep and shorter than the average open mxer, but it worked last year and it works now.

Strangely enough, with the same wheelbase and wheel travel and swing arm length and tire size, etc., some of the measurements are different. The ’82 has nearly an inch more seat height, an inch more ground clearance, the seat is farther from the pegs and the left peg is farther from the shift lever tip. Nearly as we can tell the seat-peg and peg-lever changes are adjustment and the higher seat and added ground clearance are because the new forks have longer stanchion tubes and make the bike sit up higher in front, thereby raising the middle as well. The '81 RIM 465 did feel low in front and the new one doesn’t.

Starting the new RM is much like starting the other Japanese open motocrossers—brutal. The RM might be the

worst of the bunch. The right-side kick lever has cast-in steel ridges to keep boot soles from slipping and it tucks out of the way when not in use. But if you have a foot that’s larger than a size 6, and most open class racers do, kicking in a conventional way brings instant pain. The top of your foot slams into the back side of the footpeg. Once is all you’ll try kicking the 465 with your foot straight ahead. Turning your foot so it points out from the bike at a 45° angle keeps the top of your foot from being bruised but subjects your instep just above the boot sole to the end of the peg at full bottom. Any way you do it, it’ll hurt. Making the lever a little longer seems a logical solution. All riders complained about it.

Once running things get better. The new carburetor eliminates the blubbering mid-range. The bike runs beautifully. Vibration is mild for an open bike and the heavier flywheel, clean carburetion and raised exhaust port give the RM a more powerful feel. And the increased power output is more usable as the flywheel weight helps the power get to the ground. Acceleration is quick and controllable. The front wheel may be in the air most of the time. The engine runs so well and lifts the front wheel so easily that everybody thought the bike was shorter than before, although it isn’t.

Now, some negative thoughts about four-speed gearboxes.

Motocross is more specialized than it looks. There is a definite, predictable range of speeds. An open class bike has as much power as the rear tire will put on the ground. The powerbands are wide enough to not need lots and lots of gears. Juggling rear and countershaft sprockets can give the best choice of top speed and acceleration. The open class bike doesn’t

need more than four speeds and the less shifting per lap, the better. That’s why works bikes got four-speed boxes and why the latest production models come that way. For motocross racing, fine.

What Suzuki (and Honda and Yamaha) may have forgotten is that many riders buy open class bikes and don't motocross them. They want playbikes with maximum power and handling. Or they race grands prix or desert. These riders need lower lows and higher highs. They blast across dry lakes at 100 mph and crawl across rock farms at 0.5 mph.

Next, the reasons we’ve heard for fourspeeds include the extra strength from larger gears. Last year we had a fivespeed RM465, which we rode hard for 1500 mi. It was bulletproof. No failures. On the fourth day of the 1982 test our four-speed began jumping in and out of 4th, a sure sign of a broken engagement dog.

Right this minute we don’t like fourspeed gearboxes very much. The European dirt bikes aren’t following each other quite as closely. The motocross/ playbikes from Maico and KTM have five speeds and Husqvarnas have six. We wouldn't be surprised if this gained them some customers and we wouldn't be surprised to see the Japanese return to five speeds.

That’s just one aspect though. Aside from having one less speed that it could use, the new RM465 is a superior machine. Suspension is nearly perfect at both ends. Small bumps disappear without the rider’s notice and big bumps are swallowed up without bottoming or jarring the rider. Add brakes with perfect stopping power and sensitivity and it sounds as though RM racers are going to be winning races again this year. 5!

SUZUKI RM465Z

View Full Issue

View Full Issue