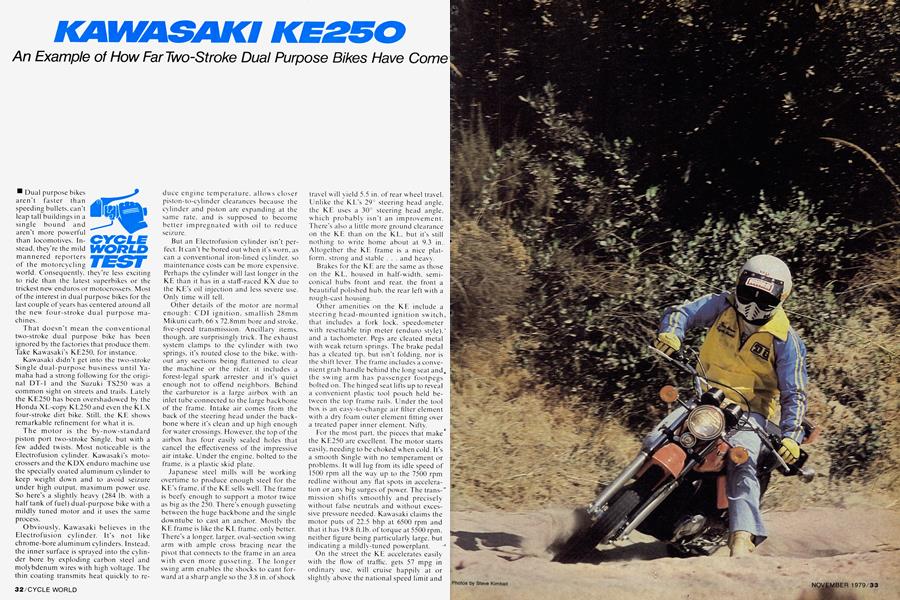

KAWASAKI KE250

cYCLE WORLD TEST

An Example of How Far Two-Stroke Dual Purpose Bikes Have Come

Dual purpose bikes aren't faster than speeding bullets, can’t leap tall buildings in a single bound and aren’t more powerful than locomotives. Instead. they’re the mild mannered reporters of the motorcycling

world. Consequently, they’re less exciting to ride than the latest superbikes or the trickest new enduros or motocrossers. Most of the interest in dual purpose bikes for the last couple of years has centered around all the new four-stroke dual purpose machines.

That doesn't mean the conventional two-stroke dual purpose bike has been ignored by the factories that produce them. Take Kawasaki’s KE250. for instance.

Kawasaki didn’t get into the two-stroke Single dual-purpose business until Yamaha had a strong following for the original DT-1 and the Suzuki TS250 was a common sight on streets and trails. Lately the KE250 has been overshadowed by the Honda XL-copy K L250 and even the K LX four-stroke dirt bike. Still, the KE shows remarkable refinement for what it is.

The motor is the by-now-standard piston port two-stroke Single, but with a few added twists. Most noticeable is the Electrofusion cylinder. Kawasaki’s motocrossers and the KDX enduro machine use the specially coated aluminum cylinder to keep weight down and to avoid seizure under high output, maximum power use. So here’s a slightly heavy (284 lb. with a half tank of fuel) dual-purpose bike with a mildly tuned motor and it uses the same process.

Obviously, Kawasaki believes in the Electrofusion cylinder. It’s not like chrome-bore aluminum cylinders. Instead, the inner surface is sprayed into the cylinder bore by exploding carbon steel and molybdenum wires with high voltage. The thin coating transmits heat quickly to reduce engine temperature, allows closer piston-to-cylinder clearances because the cylinder and piston are expanding at the same rate, and is supposed to become better impregnated with oil to reduce seizu re.

But an Electrofusion cylinder isn't perfect. It can't be bored out when it's worn, as can a conventional iron-lined cylinder, so maintenance costs can be more expensive. Perhaps the cylinder will last longer in the KE than it has in a staff-raced KX due to the KE's oil injection and less severe use. Only time will tell.

Other details of the motor are normal enough: CDI ignition, smallish 28mm Mikuni carb. 66 x 72.8mm bore and stroke, five-speed transmission. Ancillary items, though, are surprisingly trick. The exhaust system clamps to the cylinder with two springs, it's routed close to the bike, without any sections being flattened to clear the machine or the rider, it includes a forest-legal spark arrester and it's quiet enough not to offend neighbors. Behind the carburetor is a large airbox with an inlet tube connected to the large backbone of the frame. Intake air comes from the back of the steering head under the backbone where it’s clean and up high enough for water crossings. However, the top of the airbox has four easily sealed holes that cancel the effectiveness of the impressive air intake. Under the engine, bolted to the frame, is a plastic skid plate.

Japanese steel mills will be working overtime to produce enough steel for the KE’s frame, if the KE sells well. The frame is beefy enough to support a motor twice as big as the 250. There’s enough gusseting between the huge backbone and the single downtube to cast an anchor. Mostly the KE frame is like the KL frame, only better. There’s a longer, larger, oval-section swing arm with ample cross bracing near the pivot that connects to the frame in an area with even more gusseting. The longer swing arm enables the shocks to cant forward at a sharp angle so the 3.8 in. of shock travel will yield 5.5 in. of rear wheel travel. Unlike the KL's 29° steering head angle, the KE uses a 30° steering head angle, which probably isn't an improvement. There’s also a little more ground clearance on the KE than on the KL. but it's still nothing to write home about at 9.3 in. Altogether the KE frame is a nice platform. strong and stable . . . and heavy.

Brakes for the KE are the same as those on the KL. housed in half-width, semiconical hubs front and rear, the front a beautiful polished hub. the rear left with a rough-cast housing.

Other amenities on the KE include a steering head-mounted ignition switch, that includes a fork lock, speedometer with resettable trip meter (enduro style).' and a tachometer. Pegs are cleated metal with weak return springs. The brake pedal has a cleated tip. but isn’t folding, nor is the shift lever. T he frame includes a convenient grab handle behind the long seat and„ the swing arm has passenger footpegs bolted on. The hinged seat lifts up to reveal a convenient plastic tool pouch held between the top frame rails. Under the tool box is an easy-to-change air filter element with a dry foam outer element fitting over a treated paper inner element. Nifty.

For the most part, the pieces that make' the KE250 are excellent. The motor starts easily, needing to be choked when cold. It’s a smooth Single with no temperament or problems. It will lug from its idle speed of 1500 rpm all the way up to the 7500 rpm redline without any fiat spots in acceleration or any big surges of power. The trans-" mission shifts smoothly and precisely without false neutrals and without excessive pressure needed. Kawasaki claims the motor puts of 22.5 bhp at 6500 rpm and that it has 19.8 ft.lb. of torque at 5500 rpm. neither figure being particularly large, but indicating a mildly-tuned powerplant. u

On the street the KE accelerates easily with the flow of traffic, gets 57 mpg in ordinary use. will cruise happily at or slightly above the national speed limit and has a top speed of 75 mph at redline.

For a dual purpose machine, the brakes on the KE are excellent. The front brake is powerful, has good control, and takes minimal pressure to operate. The rear brake can be locked at will, but doesn’t lock unless a rider wants it to. Off road the brakes are every bit as nice as they are on pavement. They are powerful and controllable and there’s minimal fade in normal use. though a hot lap through the local mountain road will make the brakes fade.

Handling is limited by the trials tires, both on and off road. It’s not a question of one brand of trials tires being better or worse than another, it’s just that trials tires are a compromise that don't lend themselves to sporting use either on the road or off road. A knobby works far better in the dirt and is more predictable on the pavement, but isn’t street legal, though many people get away with using knobbys on the street. On the KE the tires allow moderate cornering and hard braking on the street, but make the front of the bike slide excessively in the dirt. Even sliding way up on the long, narrow gas tank and turning into a berm doesn't make the KE steer well off the pavement. A steeper steering head could help a little, but it would take a full knobby tire to eliminate the skating in front. If the KE were styled more like the modern motocrossers, with a short tank and seat moved forward, it would be easier for a rider to slide forward to gain steering control.

Off-road handling is also hampered by the weight. At 284 lb. the KE is 10 lb. lighter than the KL. but it’s heavier than Honda’s XL250 four-stroke. Most of the weight is in the strong frame, but there’s unnecessary weight in the headlight, signal lights and gauges on the KE. Removing the front signal lights isn’t an easy job, as the lights are bolted to a steel rod that’s welded to the headlight bracket. It would be far better to have a quiek disconnect package of lights and instruments so headlight, signal lights, tach. and the taillight could be unplugged easily for dirt riding.

continued on page 69

continued from page 34

Suspension travel on the KE isn’t in the MX league, not even in a competitive enduro league, but the forks and shocks are acceptable for the moderate speeds a trail bike will be subjected to. Spring rates are just about ideal for the bike's intended use. The shocks are wound with two springs, one of which is a variable rate. Minimum spring preload worked best for a solo rider off road or on, while the higher preloads were reserved for the occasional two-up riding. Landing off a hard jump could bottom the forks, but for most use. the damping and spring rates were right on. There’s minimal seal friction and they absorb small bumps and large rocks as well as any fork with 7.3 in. of travel is going to. Rather than set up the KE250 with springing and damping harsh enough for flat out running, Kawasaki has equipped the 250 for street use and trail riding and the compromise is effective.

During its stay at Cycle World the KE250 mostly was used on the street for commuting and an occasional Sunday ride. When pure dirt bikes are available, they are far more enjoyable to ride off road than any of the dual purpose machines. In its role as commuter scooter the KE performed flawlessly, with no maintenance required. The plug never fouled, the spokes didn’t loosen, nothing came loose. Even the inevitable spill off road failed to break or bend anything on the KE, despite the fragile looking signal light stems.

What the KE250 is, is good, solid, reliable go-anywhere transportation. It doesn’t have the suspension of Elonda's latest dual-purpose bikes, or the power of the larger machines, but the Kawasaki does have several novel features and rugged dependability.

KAWASAKI

KE250

SPECIFICATIONS

$1349

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1979 -

Departments

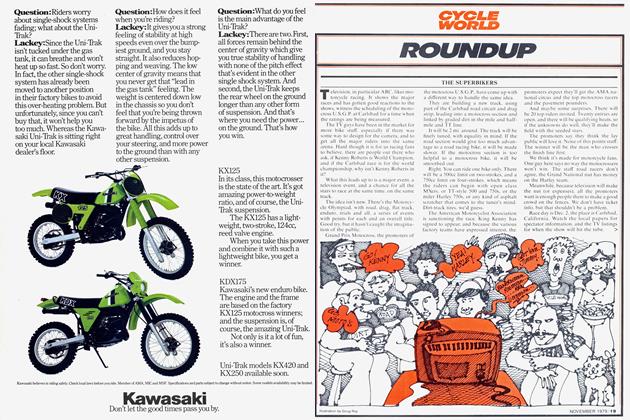

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1979 -

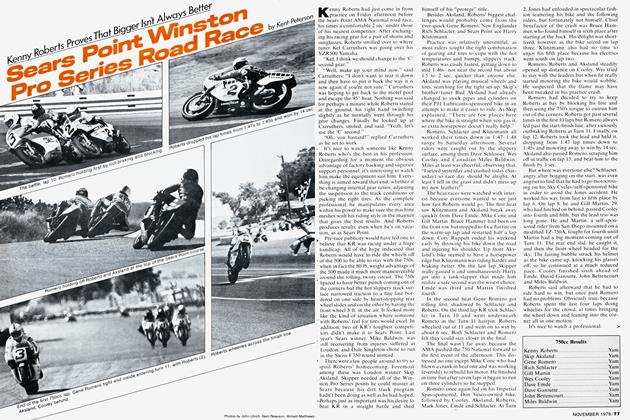

Competition

CompetitionSears Point Winston Pro Series Road Race

November 1979 By Kent Peterson -

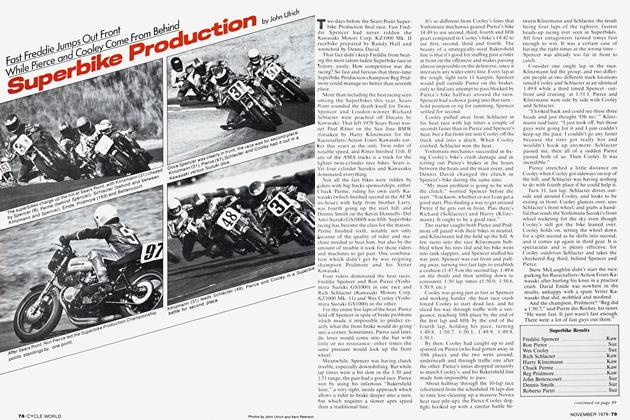

Competition

CompetitionSuperbike Production

November 1979 -

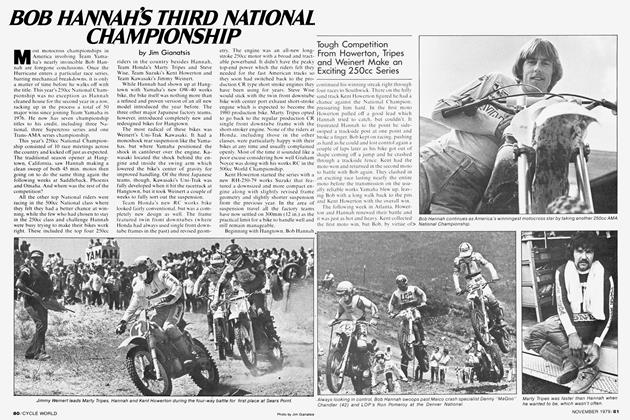

Competition

CompetitionBob Hannah's Third National Championship

November 1979 By Jim Gianatsis