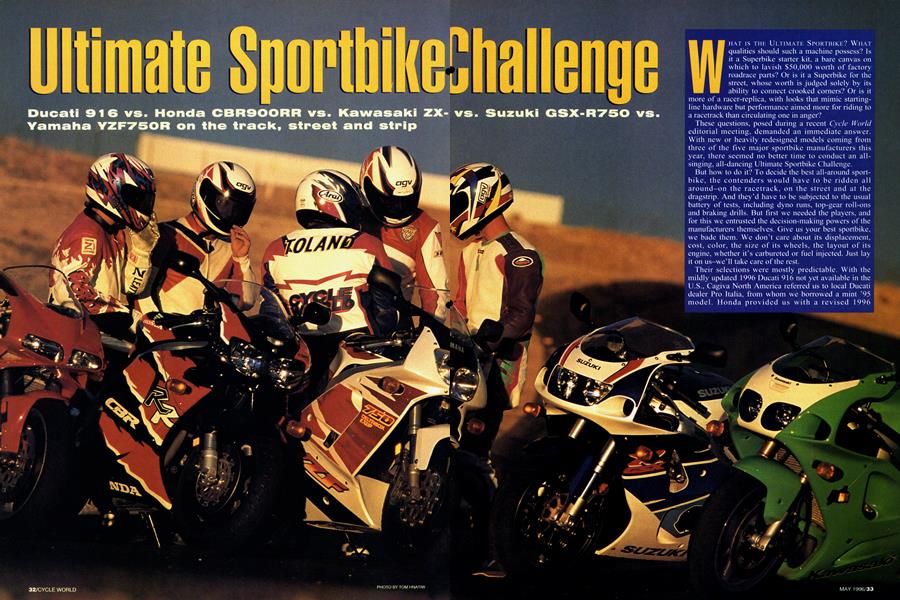

Ultimate Sportbike Challenge

Ducati 916 vs. Honda CBR900RR vs. Kawasaki ZXvs. Suzuki GSX-R750 vs. Yamaha YZF750R on the track, street and strip

WHAT is THE ULTIMATE SPORTBIKE? WHAT qualities should such a machine possess? Is it a Superbike starter kit. a bare canvas on which to lavish $50,000 worth of factory roadrace parts? Or is it a Superbike for the street, whose worth is judged solely by its ability to connect crooked corners? Or is it more of a racer-replica, with looks that mimic startingline hardware but performance aimed more for riding to a racetrack than circulating one in anger?

These questions, posed during a recent Cycle World editorial meeting, demanded an immediate answer. With new or heavily redesigned models coming from three of the five major sportbike manufacturers this year, there seemed no better time to conduct an allsinging, all-dancing Ultimate Sportbike Challenge.

But how to do it? To decide the best all-around sportbike, the contenders would have to be ridden all around-on the racetrack, on the street and at the dragstrip. And they’d have to be subjected to the usual battery of tests, including dyno runs, top-gear roll-ons and braking drills. But first we needed the players, and for this we entrusted the decision-making powers of the manufacturers themselves. Give us your best sportbike, we bade them. We don’t care about its displacement, cost, color, the size of its wheels, the layout of its engine, whether it's carbureted or fuel injected, .lust lay it on us-we’ll take care of the rest.

Their selections were mostly predictable. With the mildly updated 1996 Ducati 916 not yet available in the U.S., Cagiva North America referred us to local Ducati dealer Pro Italia, from whom we borrowed a mint '95 model. Honda provided us with a revised 1996 CBR900RR-no surprise there. Kawasaki threw us a curve with a ’96 ZX-7R, company spokesmen explaining that it would make up on the street whatever it may give away to the racier, limited-edition ZX-7RR on the track. Suzuki fielded its highly touted GSX-R750, all-new for ’96. And Yamaha Motor Corp., USA-still awaiting the all-new YZF1000 Thunder Ace (see riding impression, page 44)—loaned us the next-best thing, a ’96 YZF750R.

We met Monday morning, pulled on our leathers, velcroed on our knee pucks and hit the road for a week. By Friday night, we’d have determined 1996’s Ultimate Sportbike.

flonday i February St 2:32 p.m.

CW Executive Editor Brian Catterson napped at the side of Aliso Creek Road in the drizzling rain, the 916 parked behind him. Road Test Editor Don Canet and photographer Kirk Willis were down the road shooting photos of the CBR, and the remaining troops were en route from their lunchtime rendezvous point at Newcomb’s Ranch. It was taking longer than expected.

Suddenly, the Catman was awakened by the sound of a decelerating engine. Looking up, he was horrified to see a fairingless ZX-7 approaching. Had someone wadded a bike already?!

Luckily, it wasn’t ours. Instead, it belonged to a local club racer, identified by the Willow Springs Motorcycle Club patch on his leathers (and his slick front tire!). He was joined shortly by his buddy on a similarly outfitted CBR600F. Our guys arrived safely a few minutes later. Heart attack averted.

Monday was supposed to be an easy, 100-mile street ride from the CW offices in Newport Beach over the San Gabriel Mountains to the Holiday Inn in Palmdale. A late start, a short ride, a little street photography in the afternoon and it’d be a wrap. Instead, it rained cats and dogs, washing mud and gravel across the Angeles Forest Highway and reducing traction significantly.

Yet even in this sketchy environment, the bikes were already beginning to show their hands. When it comes to putting power down on a slippery surface, it helps if a bike’s motor has a nice, tractable power delivery. The Ducati’s thumping-great 916cc V-Twin works best in this respect, flatly refusing to spin the rear tire at the wrong moment. The Honda’s 919cc inline-Four manages this in a different way, by encouraging the rider to leave the transmission a gear tall and make use of its abundant midrange torque.

Of the three 750cc Fours, the Kawasaki’s works best, with a nice spread of midrange power that’s very user-friendly; it feels much like Honda’s vaunted VFR750. In tricky going, the others don’t fare as well. The Yamaha makes power in a predictable, linear manner, but the bulk of its ponies comes at high rpm, meaning you have to rev it to go anywhere-a potentially risky proposition in the wet. The Suzuki is even peakier, with very little low-end grunt and a hard, uppermidrange hit like a two-stroke GP bike’s. Nice for wheelies in the dry, not so good for hooking up in the wet.

Tuesday i February tn IQ: 17 a-m-

Changing tires is never any fun. It’s even worse when you’ve got 10 of them.

In the interest of testing motorcycles rather than rubber, we decided to equip all five testbikes with the same tires. That being the case, Dunlop graciously donated nine of its ultra-sticky D364 supersport-racing tires for each of our two days of track testing.

Wait a second. Did we say nine D364s? Yes, that’s correct. Because Dunlop doesn’t make a D364 to fit the CBR’s 16-inch front wheel, the company substituted a race-compound Sportmax II. Close enough.

Today’s testing would go down on the full Streets of Willow Springs circuit, which uses a portion of the facility’s skid pad (see course outline, page 42). This 1.5-mile, nine-turn layout features mostly second-gear comers, placing a premium on acceleration, braking and a bike’s ability to change direction quickly. Top speed at the end of the front straightaway is less than 110 mph (as indicated by the CW radar gun), making the track a nice compromise between the ungodly fast Willow Springs Road Course and mortal street-riding speeds.

Now, racetrack prowess is measured in seconds, and what better way to gauge lap times than to enlist the help of experts? For the past few seasons, AMA Pro Racing has been using electronic timing and scoring at its roadracing nationals, using cables buried under the track and a small transponder affixed to each bike. So, we wondered, would the AMA be willing to help out with our testing?

Sure it would. The association sent Road Race Manager Ron Barrick out West for a well-deserved break from the frigid East Coast winter, providing us with a virtually effortless way of recording accurate lap times.

It didn’t take long for the Ducati to begin showing signs of why it is the reigning World Superbike Champion. Despite making the least peak horsepower of the group, it turned the quickest lap time of the day. With Canet in the saddle, the 916 circulated “Little Willow” almost a half-second quicker than the runner-up Suzuki.

Much of this is due to the Ducati’s abilities to put the power down coming off corners, and to accurately communicate to the rider what’s going on at the tires’ contact patches. Though the 447-pound machine steers somewhat heavily, it rails comers like a 250cc GP bike, and its raceworthy Showa front and Öhlins rear suspension are all but unaffected by mid-corner bumps.

At 422 pounds, the Suzuki weighs the least of the bikes in this group, and has extremely light steering that makes it easy to flick from side to side. The tradeoff, however, is a touch of twitchiness, as the GSX-R wags its head under acceleration-a steering damper would help greatly. Its Showa rear shock feels as though it has too little rebound damping, yet the chassis retains its composure in comers.

The Honda weighs just 2 pounds more than the Suzuki, steers every bit as easily, and was a mere tenth of a second slower around the racetrack. Its main shortcoming remains a tendency for the front tire to dance over rippled pavementno cause for alarm, merely something that takes a little getting used to.

At 486 pounds, the Kawasaki weighs the most, and feels like it; you need to strong-arm it into a comer. It was a couple of tenths slower than the Honda. The Yamaha tips the scales at a relatively heavy 469 pounds, but feels lighter, with the best combination of steering ease and stability, plus the most powerful brakes. But while the Yamaha’s chassis is up to snuff, its motor lacks power, resulting in a best lap time more than a second off the Ducati’s. That doesn't sound like much, but it adds up to a lot over race distance.

Wednesday! February 7i 12:3e! p-m-

CW Test Consultant Doug Toland flashed past the radar gun on the Suzuki, the LCD showing his speed as 164 mph. Huh? Normally, the prospect of a 750 going this fast would be cause for celebration, but the first ’96 GSX-R we tested two months ago went 166 mph.

More bafflement was yet to come. Mere seconds later, Canet was radar-gunned at 166 mph on the ZX-7R-the same bike that had “only” managed to go 163 during our previous road test. So much for top-speed testing being predictable.

The others’ results were, however, as anticipated. The Honda went 162 mph, the Ducati 159 and the Yamaha 154-good a couple of years ago, but slow by today’s standards.

Top-speed runs completed, we returned to the day’s scheduled track testing. Today we were at the 2.5-mile, nine-turn Willow Springs Road Course, a high-speed circuit that favors horsepower, cornering speed and stability.

Turn Eight separates the men from the boys-and, occasionally, the boys from their bikes. Taken in the top of fifth gear on a production bike, ground speed is in the vicinity of 145 mph. With the bike squirming about. And your knee on the deck. Not a place for the faint of heart.

Because Toland had notched a recent string of race wins at “Big Willow” aboard a Ducati 955, we figured he’d do well on the 916. And he did, turning the quickest lap of the day. Yet Canet, who has never raced a Ducati anywhere, managed to circulate within a couple hundredths of a second of Toland.

The Ducati could well have gone even faster if it hadn’t been for the fact that its stock gearing is way too tall for Willow, leaving it awkwardly between ratios at various points of the circuit. Some comers had to be taken a gear lower than normal with the engine revving out, forcing a time-wasting upshift at the exit. Moreover, the 916 was 6 mph slower than the fastest bike, the Suzuki, at the end of the front straight. Trust us, this thing really shines in the comers...

The rest of the finishing order could have been predicted by looking at the previous day’s results. The Suzuki was again second, though this time only by a couple of hundredths. The Honda was next, down 5 mph on top speed. Canet managed to turn a respectable lap aboard the Kawasaki, but he was cheating death the whole way, dragging the exhaust canister in every right-hand corner-more rear ride height is needed. On another bike this could have spelled disaster, but the 7R’s ultra-stable chassis let Canet get away with such antics; it may steer heavily, but it flies straight and true. The Yamaha was slowest again, hurt by its lack of speed and a chassis set-up problem that caused the front tire to wear faster than the others’. We changed the tire, but the problem persisted.

Thursday~ February 2~, 9:54 a.m. Figures it would be Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis who led us into a gravel trap. A mere half-hour into the day's 300-mile Street ride and already we'd struck trouble. - -

Riding down Big Pines Highway at a sedate pace (really), our group entered a shaded, right-hand corner. Lewis and Toland proceeded right on through, but Canet's ZX-7R sud denly slewed sideways, his feet flying off the pegs. Catterson veered right to avoid him and promptly spun the YZF out, landing uninjured on his rump. Canet, due to his racetrack experience (he'll tell you) or to dumb luck (we believe), managed to wrestle the green bike to a stop with out toppling over, a scuffed boot his only wound.

Fortunately, the YZF wasn t badly hurt and was able to proceed with testing, its only real damage a busted rightside fairing panel.

So we soldiered on. With street-compound Sportmax Ils fitted all around the previous evening, today’s route would encompass mile after mile of twisty two-lane, taking us over the San Bernardino and San Jacinto mountain ranges for a little high-altitude (8000-plus feet) carburetion testing. Here, we expected the Ducati to excel, as its fuel-injection system automatically compensates for the reduced-oxygen content of mountain air. But, in reality, all the bikes lelt equally affected, with a noticeable lack of acceleration.

Not that we had much use for it. As the day wore on, we had plenty of reasons to knock back the throttles. Highway 38 out of Big Bear w'as lined with snow, and 243 approaching Idyllwild was a dirty mess, legacy of the snow-removal crews. Caution was the watchword of the day, and our long stints of relative slow-going gave us plenty of time to ponder the bikes' comfort levels.

In this respect, the Ducati does not shine as brightly. Its thin rubber seat pad may be an acceptable place to sit for a 45-minute roadrace,

but it’s hardly up to the rigors of sport-touring. Furthermore, its high footpegs and low, clip-on handlebars lorce the rider into a severe racing crouch, its mirrors are useless, the windscreen is ineffective if you sit up and the right-side exhaust pipe burns the calf of your boot.

The Kawasaki is equally uncomfortable. Its seat is better padded, but the reach to its low-set clip-ons is too far, forcing the rider to lean radically forward with his arms out straight; even 6-footers found this painful. Plus, the 7R's fork gives a jarring ride on the street; without any provision for increasing spring preload (it's adjustable lor ride-height only), it rides dow n in the harsh part of the stroke.

The Yamaha is better, thanks to its thinner fuel tank, lower footpegs and nice, flat seat. You feel a part of the YZF, instead of perched on top, and the windscreen is tall enough to divert some of the windblast. Though it’s a pussycat at low rpm, our main complaint is excessive vibration at higher revs.

As for the Honda and Suzuki, both are relatively comfortable, with cushy saddles, reasonable bar-to-seat relationships and footpegs that aren’t painfully high. On the downside, the Honda has a fat fuel tank that splays your legs to the limit, while the Suzuki is a bit buzzy and has too much driveline lash. And both bikes’ windscreens are too low to provide any real wind protection. The Honda, by virtue of having its clip-ons rise above the triple-clamps, gets the nod as the most comfortable.

Relaxing that evening at the Best Western in Carlsbad, conversation turned to the morning’s crash. How much does a YZF fairing panel cost, anyway? And how much would it cost to replace a comparable part on the others? When we got back to the office, we called a few shops for quotes.

Everyone knows body parts are expensive-ask any insurance adjuster. And it’s little surprise that the Italian Ducati rings the cash register bell loudest, with a $470 price tag. The Japanese bikes’ parts range from $335 for the Honda to $383 for the Suzuki, with the others falling in between.

A Bondo repair kit costs about $20, though your results may vary.

Another question often posed by potential owners is, how much does a full service (valve adjustment, oil and filter change, etc.) cost? And how often does that work need to be performed?

Another flurry of phone calls revealed that the Ducati is once again most expensive, thanks to its complicated desmodromic valve-actuation system. Figure on $240-480, depending on how many shims need changing. The good news is that despite the frequent 6000-mile service interval, the 916’s shims don’t need changing that often, just checking.

As for the Ducati’s less-complicated competition, they all cost less: The Honda only needs a full tune-up every 16,000 miles at a cost of $250; the Kawasaki every 7500 miles for $230; the Suzuki every 7500 miles for $300; and the 20valve Yamaha every 16,000 miles for $400.

Friday! February T! 7:1b a-m-

After spotting our bikes in the Denny’s parking lot, photographer Willis comes inside with the grim weather report: The fog is even worse at the dragstrip than it is here; our planned early-morning photo shoot is a wash.

Damn. Wish we’d known that before we'd crawled out of bed.

Fortunately, the conditions improve by mid-morning, and track testing commences.

As expected, the Honda and Suzuki were immediately in the running for quarter-mile honors, with the GSX-R eventually claiming the top spot. Both bikes are wheelie-prone, making them hard to launch, but they’re so strong on top that they managed to post the quickest times.

The Kawasaki was the easiest to launch, tying with the Honda for quickest 0-to-60-mph time, but it was a few mph down on trap speed, costing it a couple of tenths over the quarter-mile. The Ducati’s finicky (by drag-racing standards) dry clutch and tall gearing conspired to hinder its acceleration, landing it in fourth place. Truth be told, by day’s end the 916 was unridable, its friction plates completely burned up. The Yamaha was even farther off the mark, its grabby clutch landing it in last place.

The Ducati also fared poorly in top-gear roll-ons, again a function of its gearing. With a narrower rev range than the others-it has the lowest rev limit, at 10,200 rpm-the 916 needs tall overall gearing and a relatively wide-ratio tranny to give it comparable top speed.

Taking roll-on honors, and confirming our seat-of-thepants impressions, was the Honda, with the Kawasaki second, the Suzuki third and the Yamaha fourth.

Brake testing also confirmed our previous impressions. The Yamaha posted the shortest 30-mph-to-zero distance, while the Suzuki was best from 60-to-zero.

And the winner is...

Putting 1000 miles on these sportbikes between Monday and Friday was a motorcyclist’s dream vacation. Never have there been so many supremely capable machines on the market at once. After living with them for a week, asking us which one we like best is like asking a mother which one of her quintuplets she loves most.

Yamaha’s YZF750R was a fabulous machine when it debuted in 1994, and continues to be so today. It has the best steering and brakes of the bunch, a racy yet comfortable riding position, and a nice, linear power curve. Want more juice? Hold the throttle on longer.

It’s only when you compare it to the others that the YZF starts to look dated. Two years is an eternity in the Sportbike Wars, and the YZF is getting long in the tooth. Plus, at $10,499, it's the second most expensive bike here. Sorry, Yamaha, but someone has to finish last.

In racing trim, Kawasaki’s ZX-7R is destined for supersport greatness. It has the most midrange power of any 750, the highest top speed and the most stable chassis of any sportbike-period. But it’s uncomfortable on the street, its fork is harsh and, in stock trim at least, it runs out of ground clearanee on the racetrack. It is, however, reasonably priced-at $9,399, it’s the second thriftiest bike here. A solid fourth place.

Now, things start to get complicated. Any one of the remaining three bikes could be a w inner, depending on the criteria you use to judge them. Here’s our take:

With its svelte and sexy bodywork, Ducati’s blood-red 916 is the ultimate Sunday-morning ride, sure to draw a crowd wherever it’s parked. The mechanical symphony playing inside its fairing is music to gearheads’ ears. It feels the most like a Superbike, and it works like one, too, winning every aspect of our testing that had a comer in it.

Of course, some of the qualities that make the 916 fastest on the racetrack hurt it in general street use, where it’s more than a little uncompromising. And with a $15,700 price tag-over $5000 more expensive than the next priciest bike-it asks its owner to make a serious financial commitment. It pains us to do this, but we award the Ducati third place.

From this point on, it’s almost too close to call. Honda did everything right in making over the CBR900RR, already the leading liter-class bike, with a power-to-weight ratio that was revolutionary when the Double-R was introduced in 1992. Complaints about its predecessor’s radical seating position have been addressed for ’96, making the revised CBR the best day-tripper of this lot. At $9,799, it stands the middle ground, price-wise. A very, very close second place.

Which leaves the Suzuki GSX-R750, the closest thing yet to a street-legal GP bike. No, the Gixxer isn’t perfect, but it picks up where the CBR left off in the power-to-weight department. Not only is the GSX-R impressive for a 750, it outperformed the 900RR in nearly every aspect of our performance testing. Yes, it's an expert’s bike; but then, novices shouldn’t be shopping for 750cc-plus sportbikes, should they? Plus, at $8,999, the Suzuki is the least expensive bike in this test, offering the greatest possible bang for your buck. What more compelling argument could there be for naming it the Ultimate Sportbike of 1996? □