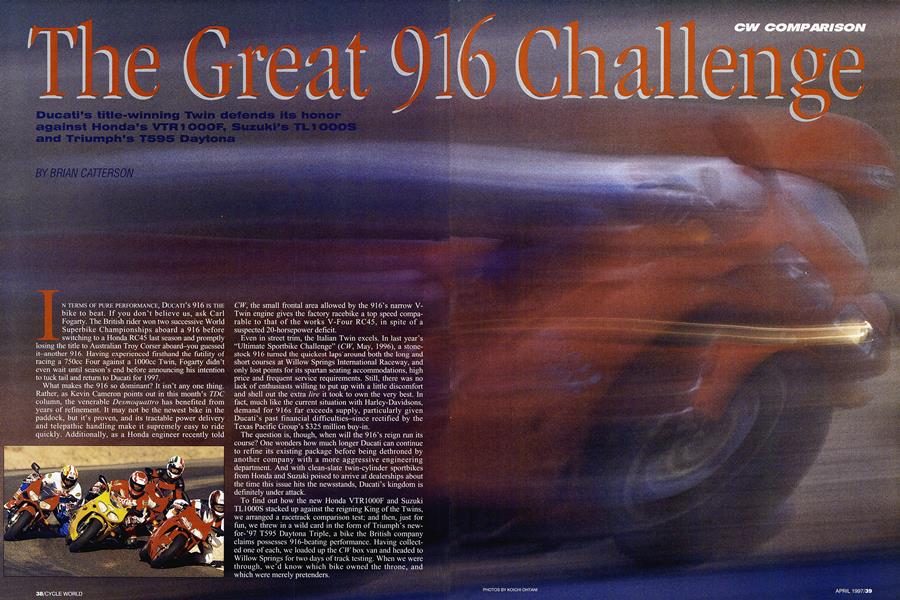

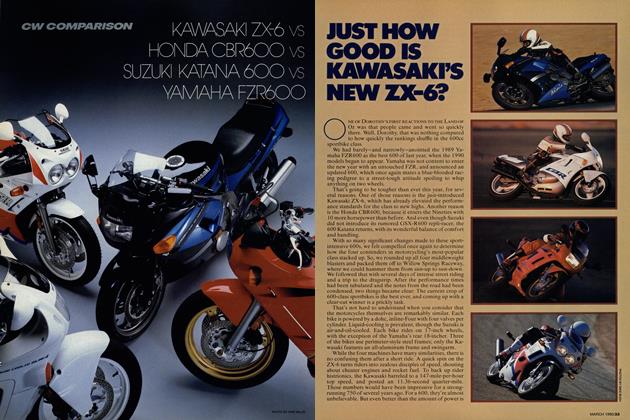

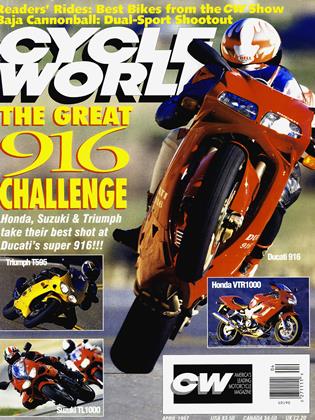

The Great 916 Challenge

Ducati's title-winning Twin defends its honor against Honda's VTR1000F, Suzuki's TL1000s and Triumph's T595 Daytona

BRIAN CATTERSON

IN TERMS OF PURE PERFORMANCE, DUCATI'S 916 IS THE bike to beat. If you don't believe us, ask Carl Fogarty. The British rider won two successive World Superbike Championships aboard a 916 before switching to a Honda RC45 last season and promptly losing the title to Australian Troy Corser aboard—you guessed it—another 916. Having experienced firsthand the futility of racing a 750cc Four against a 1000cc Twin, Fogarty didn't even wait until season's end before announcing his intention to tuck tail and return to Ducati for 1997.

What makes the 916 so dominant? It isn't any one thing. Rather, as Kevin Cameron points out in this month's TDC column, the venerable Desmoquattro has benefited from years of refinement. It may not be the newest bike in the paddock, but it's proven, and its tractable power delivery and telepathic handling make it supremely easy to ride quickly. Additionally, as a Honda engineer recently told

CW, the small frontal area allowed by the 916's narrow VTwin engine gives the factory racebike a top speed comparable to that of the works V-Four RC45, in spite of a suspected 20-horsepower deficit.

Even in street trim, the Italian Twin excels. In last year's "Ultimate Sportbike Challenge" (CW, May, 1996), a stonestock 916 turned the quickest laps'around both the long and short courses at Willow Springs International Raceway, and only lost points for its spartan seating accommodations, high price and frequent service requirements. Still, there was no lack of enthusiasts willing to put up with a little discomfort and shell out the extra lire it took to own the very best. In fact, much like the current situation with Harley-Davidsons, demand for 916s far exceeds supply, particularly given Ducati's past financial difficulties-since rectified by the Texas Pacific Group's $325 million buy-in.

The question is, though, when will the 916's reign run its course? One wonders how much longer Ducati can continue to refine its existing package before being dethroned by another company with a more aggressive engineering department. And with clean-slate twin-cylinder sportbikes from Honda and Suzuki poised to arrive at dealerships about the time this issue hits the newsstands, Ducati's kingdom is definitely under attack.

To find out how the new Honda VTR1000F and Suzuki TL1000S stacked up against the reigning King of the Twins, we arranged a racetrack comparison test; and then, just for fun, we threw in a wild card in the form of Triumph's newfor-'97 T595 Daytona Triple, a bike the British company claims possesses 916-beating performance. Having collected one of each, wc loaded up the CW box van and headed to Willow Springs for two days of track testing. When we were through, we'd know which bike owned the throne, and which were merely pretenders.

CW COMPARISON

Ducati 916

Now entering its fourth season, Ducati's 916 doesn't seem that high-tech anymore. True, its Weber fuel-injection system set the standard when it debuted on the 1990 851, but its desmodromic valvetrain and steel-trellis frame are quaint at best.

Positive valve actuation made sense when Dr. Fabio Taglioni introduced it to Ducati's works racers in the 1950s, because the

The 916's steel-trellis frame doesn't trace its roots back quite as far as its valvetrain, but it is remarkably similar to that of Ducati's 1981 TT2 racer. Aluminum has long since replaced steel as the sportbike frame material of choice, but the latter continues to work quite well-especially when used as sparingly as on the 916, which like all recent Ducatis pivots its swingarm in its engine cases, thus saving the weight of traditional pivot plates.

But while the 916's frame is made of good old-fashioned steel tubing, its swingarm is cast aluminum, in the interest of increased rigidity and reduced unsprung weight for better suspension compliance. Even better, that swingarm is single-sided, which simplifies tire changes because you don't have to disturb the drive chain to remove the rear wheel. Another neat touch is an adjustable steering head, the rake

unrefined metallurgy of the era meant that valve springs couldn't cope with high revs. The desmo system of opening and closing the valves via rocker arms gave those old Singles previously unheard-of redlines, with no possibility of valve float.

Given today's materials and multi-valve cylinder head technology, however, production motorcycle engines equipped with traditional coil valve springs regularly rev far beyond the 916's 10,000-rpm redline. Furthermore, rocker arms are largely a thing of the past, as most modern engines' cam lobes act directly on the valves via inverted buckets.

of which can be altered by 1 degree via concentric inserts.

Underlining the 916's sporting intent is a full complement of race-quality components, including a steering damper, a Showa inverted fork, an Öhlins shock, Brembo four-piston brakes, Marchesini wheels and Michelin Hi-Sport Radial tires.

This year, the 916 is available in two flavors-the standard single-seat model tested here and a Biposto model, which is identical save for its passenger accommodations, steel (rather than aluminum) subframe and Showa shock. Price for either is $15,995. And as the saying goes, you can have any color you want as long as it's red.

Honda VTR1000F

Finally! After nearly a decade of turning a deaf ear, Honda has answered the cries of w enthusiasts calling for a literclass V-Twin sportbike. The 1988 Hawk GT proved that Big Red could build a sporting Twin, but while that machine was praised for its avant-garde styling and precise handling, the paltry 38 horsepower produced by its 647cc engine severely limited its performance, and thus sales. The 100-horsepower VTR1000F redresses that shortcoming quite handily.

As far back as the early '80s, American Honda's R&D staff built a prototype sport-Twin that incorporated a ParisDakar Rally racer's motor in a VT500 Ascot chassis. Later, after witnessing the success of Two Brothers Racing's Kevin Erion in AMA Pro Twins competition, those same employees built a road-going replica of Erion's racebike, with an 800cc V-Twin engine from a European-model Africa dualpurpose bike shoehomed into a Hawk GT chassis.

Honda Japan was impressed by both prototypes, though it declined to produce such a machine. But as Ducati became more successful in Superbike racing-and, in turn, in the marketplace-Honda's European distributors began to echo America's cries for a big-bore sport-Twin, and the decision was made to proceed.

Known as the Fire Storm in Europe, the VTR 1 OOOF goes by the name Super Hawk in the U.S., in homage to the company's original sport-Twin, the 1961 305 Super Hawk-a machine that ironically was also inspired by the Italian motorcycles of its day. According to a proud R&D staffer, the VTR1000 project was so successful that his department started out testing the bike alongside a Ducati 900SS, but ended up comparing it to a 916.

In designing the Super Hawk, Honda's engineers examined those two Ducati models and set about improving their basic layouts. To keep the VTR's wheelbase at a short 56.3 inches, they tilted the forward cylinder back away from the front wheel, and duplicated Ducati's pivotless chassis design. The Japanese then went the Italians one better, giving the VTR an aluminum frame that combines rectangular upper spars with lower trellis sections made of D-shaped tubing. Somewhat disappointingly, however, the engineers opted to equip the VTR with a contemporary double-sided, box-section aluminum swingarm rather than a single-sided one, thus negating one of the most recognizable design features of the Hawk GT-or, for that matter, the 916.

One unique aspect of the Super Hawk's frame is its use of variable-stiffness motor mounts-the bolt closest to the swingarm is hollow, the next one less so, and the one closest to the steering head is solid-to allow a modicum of engine/swingarm movement. In recent years, engineers have learned that chassis flex isn't all bad; in fact, through racing, they've discovered that too-stiff frames tend to feel vague at the limit, and hinder handling by failing to absorb mid-corner bumps at severe lean angles.

So, drawing on the lessons learned in re-engineering the 1996 CBR900RR, Honda's engineers reduced the VTR's chassis stiffness to the point that it is 40 percent less rigid than the aforementioned '96 CBR-itself 5 percent less rigid than its predecessor! The VTR's original-fitment Dunlop D204 radiais were thus tailored accordingly, prompting the same Honda R&D staffer to warn us that fitting aftermarket tires could cause instability. More on that later.

Almost as unusual is the VTR's weight distribution, which biases 53 percent of its 452 pounds toward the rear wheel (a 50/50 balance is the established norm). The point of this exercise is said to be improved rear tire traction.

Unlike the other three motorcycles in this comparison, the VTR's 90-degree V-Twin is carbureted rather than fuelinjected, via a pair of slant-body Keihin flat-slide CVs. At 48mm, these are the largest ever fitted to a production motorcycle-so large, in fact, that Honda enlisted the aid of fuel-injection engineers who had experience with such gaping venturis.

Also worthy of discussion is the VTR's cooling system. Instead of fitting a single large radiator behind the front wheel, Honda's engineers opted for a pair of smaller sidemounted radiators turned at right angles to the airstream. The low pressure zone created by air passing over vents in the bodywork is then used to draw air through from behind the radiators. The dual benefits here are a smaller frontal area and airflow that isn't obstructed by the front tire and fender-the latter, like the rest of the $8999 machine, is painted red. Naturally.

Suzuki TL1000S

Suzuki's TL1000S will go down in his tory for a number •ofreasons. One is the fact that it's I the company's first-ever V-Twin sportbike; another is that it took Honda completely by surprise.

So well-kept a secret was the TL1000S project that not even the world's largest motorcycle manufacturer knew it existed. In fact, American Honda originally announced a tentative price of $9199 for the VTR1000F, before lowering that figure by $200 to match the TL's suggested retail.

As was the case at Honda, Suzuki's draftsmen took a long, hard look at the 916 before drawing up the TL. And in fas cinating fashion, they concocted a totally different set of solutions to the Ducati's "problems."

Like their counterparts at Honda, Suzuki's engineers tilted the 90-degree V-Twin's forward cylinder back from horizontal. But first, they shrunk the cylinder heads by forgoing the traditional camchain and sprockets in favor of a hybrid arrangement that uses chains from the bottom end to turn gears in the top end; intermediate reduction gears let the cams turn at the required half-crank speed.

Next, rather than pivoting the swingarm in the engine cases like the 916 and the VTR, Suzuki's decision-makers opted to retain a traditional frame-pivot setup and fit a space-saving Kayaba rotary damper in place of an ordinary coil-over shock. This works in conjunction with a separate spring located behind the bottom-most, right-side spar of the TL's aluminum-trellis frame, each suspension component working through its own linkage.

Fuel injection has been absent from Suzuki's motorcycle line since the ill-fated 1983 XN85 Turbo, but it's back on the TL1000. Feeding the single-injector system is a twostage ram-air intake that varies airbox intake volume to match rpm via an electronically controlled flapper valve. Other novel technical features include a reed-valve-style crankcase breather, an automatic compression release that eases starting, and a sprag clutch that eliminates wheel chatter during downshifts.

There's no denying that the TL's red, red bodywork (it's also available in dark green) resembles that of the 916. And it's interesting to note that, like the VTR, the TL shares the same cylinder dimensions (98mm bore/66mm stroke) as the 996cc works Ducati Superbikes. But perhaps the most incredulous item Suzuki "borrowed" from Ducati was the "TL" designation, which the Italian company used on its quarter-fairing Pantah models in the 1 980s.

Triumph 1595

Triumph's nextgeneration Daytona 900 isn't red, and it isn't powered by a V-Twin engine. But like the three sport-Twins, the mustard-yellow Triple is a viable alternative to the fourcylinder Japanese norm, thus we saw fit to include it here.

Truth be told, the Britbike has quite a lot in common with the other machines in this test. Like the VTR and TL, it features an aluminum-trellis frame with the engine employed as a stressed member. Like the 916, it is equipped with a single-sided swingarm. And like the 916 and the TL, it is fuel-injected, via a system made by an Anglo-Lrench company called Sagem, whose products grace Peugot's and Renault's F-l car racing engines.

More than mere EFI, the black box under the T595's seat in fact houses a sophisticated engine-management and diagnostics system, with functions such as ignition timing and fuel flow through the dual 41mm injectors easily adjustable by technicians with the aid of a hand-held computer (see "EFI at Last!" page 44). Feeding the EFI is a pressurized airbox, which inhales through slots beneath each of the twin ellipsoidal headlights.

Though it's tempting to say that the Daytona was given a facelift, it's more accurate to call it a brand-new motorcycle. Because in addition to its all-new frame and bodywork, its engine barely resembles the previous-generation lumps, thanks to a thorough redesign intended to trim weight and boost performance.

With the help of another noted F-l firm, Lotus Engineering, the T595's cylinder head was completely reworked. In addition to the usual hotter cams and bigger valves, the intake and exhaust ports were effectively extended beyond their tracts by carefully shaping the throttle body bores and the investment-cast stainless-steel header pipes.

Downstairs, the inline-Triple received new aluminum, slip-in wet liners, whose 79mm bores (3mm larger than last year) are coated to resist wear using a Nikasil-type process. Inside the new cylinders are new semi-forged pistons that are said to weigh the same as their smaller predecessors. The crankshaft wasn't neglected, either, as it was heat-treated, then plasma nitride-hardened, polished and balanced.

Capping off the T595's weight-loss program are reshaped aluminum engine cases that more closely follow the contours of the internals; magnesium clutch, cam and breather covers; and a plastic sprocket cover. According to Triumph, the sum total of these changes is a weight savings of more than 26 pounds-on the engine alone!

Rounding out the T595's high-quality package are a fully adjustable Showa fork and shock, Nissin brakes with steelbraided lines, and Brembo wheels shod with dual-compound Bridgestone tires. Available in yellow or black, the $10,695 Daytona comes with a two-year, unlimited-mileage warranty (twice as long as the other bikes'), plus a high-quality toolkit and an instructional video.

Gentlemen, start your engines

We've introduced the steeds, now meet the jockeys. To ensure that we were getting the most out of each bike at Willow Springs, we assembled four of the fastest test riders in U.S. motorcycle magazinedom: Cycle World's Road Test Editor Don Canet, 35, a former top-ranked WERA Endurance and Formula USA competitor and

g instructor at Dennis Pegelow's dp e ti e Safety School; CW's Testing Consultant Doug Toland, 34, a former World and National Endurance Champion and the current AMA SuperTeams number-one plate-holder with Erion Racing; Nick Ienatsch, 35, newly named editor of our Sportbike magazine, perennial AMA 250cc GP front runner, two-time Willow Springs track champion and instructor at Freddie Spencer's new High Performance Riding School; and Lance Hoist, 32, a former Ienatsch cohort at Sport Rider magazine, 1995 Willow Springs Motorcycle Club Champion and director of the Advanced Riding Tech School.

Clearly a talented group, with literally thousands of laps around Willow Springs between them. Individually, each is capable of pushing a bike to its limit, but we were curious what they could do together, while pushing one another. Might we see a new lap record for a production streetbike?

To find out, we arranged four five-lap sprint races, with each tester riding each bike once. But first, to make matters as fair as possible, we fit each bike with a set of Dunlop's new D207 Supersport racing radiais, and mounted on-board lap timers from Unipro (distributed by World Dynamics, 508/670-8900).

It didn't take long to determine that the Honda and the Triumph were out of their element at Willow, as the two bikes took turns finishing last. With the aforementioned warning about switching the VTR's tires ringing in our ears, we made sure our testers reeled off a bunch of laps on the stock skins, and it was Canet who set the quickest VTR time (1:30.25) before the tires turned greasy.

All were impressed by the Honda's comfortable seating position, mile-wide powerband, tractable delivery and flawless caburetion. And initially, all praised the bike's stability, light steering and front-end feedback-but those latter impres sions faded as soon as we spooned on the V-profile, racecompound Dunlops. Just like we'd been warned, the VTR's handling took a dramatic turn for the worse, making for a nervous, confidence-sapping ride. Even raising the forks 7mm in the triple-clamps (per Dunlop's specs) didn't help-especially since it let the footpegs and exhaust header touch down that little bit sooner. The VTR' s antics bothered Canet least, however, as he again posted the quickest VTR hin (1 2X~1 6~ c1urin~ the rnces~

The Triumph's handling wasn't adversely affected by the race tires, but it was not without its problems. The most seri ous handicap was a lack of cornering clearance that let the header pipe and fairing lower ground in right-hand turns. In fact, Holst-the heaviest of our four testers at 160 pounds-wore a hole through his right boot during his stint on the T595. The main culprits here were too-soft fork and shock springs; cranking up the spring preload didn't help, because it overwhelmed the shock's rebound damping capabilities.

Our testers also criticized the Triumph's wide handlebars, whose added leverage exaggerated steering inputs, making for a twitchy ride. And they didn't muáh care for the overly sensitive clutch, the sloppy gearbox, or the glitch in the fuel injection that gives the T595 a huge flat spot between 4500 and 6750 rpm. The big Triple has impressive low-end torque, and its peak horsepower figure (104 bhp at 9250 rpm) is the second highest in this test; it just needs to have its EFI fine tuned for smoother delivery.

g The Triumph's limitations make Toland's iii e performance on the bike that much more heroic, as he grabbed the holeshot at the start of race one and led for a lap before Canet and the Suzuki came by on the brakes to begin lap two. Toland continued to press hard for the remaining four laps, and his resultant best lap (1:27.95) aboard the T595 was never equaled.

The fact that the Honda and the Triumph got beat on the racetrack in no way means that they're worthless piles of junk. To the contrary, both are fine motorcycles that just hap pen to be better suited to street riding than to roadracing. This should come as no surprise, really, because both manufactur ers have said that their racing models are a generation away. Triumph, in fact, purposely made the T595's 955cc engine too big for Superbike racing, in order to give street riders the midrange power they demanded; and a Honda engineer recently told CWthat he's already seen 150 horsepower from a hot-rodded VTR motor. Stay tuned.

Much more at home onthe racetrack was the Suzuki, though it wasn't perfect, either. We lauded the TL's handling following its introduction at Miami's Homestead Motorsports Complex, but between the bumpy surface and the triangulat ed front Dunlop, it was a wobbler at Willow. As with the Honda, we pulled the fork tubes up in the triple-clamps, and while this improved matters significantly, the TL's chassis never felt entirely composed.

To its credit, the Suzuki has the strongest motor of this bunch (111 bhp at 8250 rpm), which gave it the highest top speed (143 mph) down Willow's front straight. No doubt, this contributed to the hot lap time (1:27.23) Toland turned on the TL, which may have gone even quicker had it not been for a confidence-sapping vibration caused by a slight tread separation in the rear tire. Willow's flat-out Turn 8 is notoriously tough on tires.

As impressive as the Suzuki is on the racetrack, however, its primary intent is sporting street riding. In fact, at the recent TL press intro, a company spokesman dismissed jour nalists' queries about a racing program, saying only that he believes the TL's engine has "great potential" for racing. Interpret that any way you wish.

LI1~L aiiy way yvu W1~11. Which leaves the Ducati. True to form, the 916 dominated at Willow. It won twice, finished a close second to the Suzuki once, and likely only finished third in the other out ing because Hoist lost time taking evasive action when Ienatsch nearly high-sided the Honda in front of him crest ing Turn 6. After that, the pair chilled out a bit, neither one wanting to toss a testbike in his CW debut.

Even so, three of our four testers not only went faster dur ing the races on the 916 than they did on any of the other bikes, they also lowered their personal-best lap times on pro duction streetbikes. And earlier in the proceedings, under less-windy conditions, two of our testers went even faster on the 916, with Hoist clocking a 1:28.80 and Toiand a smolder ing 1:25.83, the latter a new production-bike record, surpass-

ing the 1:28.05 he turned on a 916 during last year's test.

The Ducati's greatest strength is sensitivity. Even the smallest change in throttle setting causes a weight transfer that the rider can feel through the handlebars, and which he can use to make finite traction adjustments. Furthermore, the 916 is all but unaffected by mid-corner bumps, its sus pension remaining taut and its chassis stable at all times. And with its underseat mufflers, cornering clearance is vir tually limitless, meaning that it's almost always possible to tighten your line. You never run out of road on a 916.

Our Ducati made just 100 peak horsepower-same as the Honda, and the lowest in this test-on the CW rear-wheel dyno, yet it somehow posted the highest number (154.7 mph) on our radar gun during top-speed testing. Even more impressive, our testbike was literally uncrated at European Cycle Specialties on Thursday, broken-in during a photo shoot on Friday, and then, with nothing more than new tires and minimal suspension adjustments, proceeded to circulate Willow Springs faster than any production streetbike in his tory. If that doesn't earn it the right to the sportbike throne, what does?

The king ain't dead-in fact, he's not even breathing hard.~

HORSEPOWER & TORQUE

DUCATI 916

HONDA VTRI000F

SUZUKI TLI000S

TRIUMPH T595

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Oakland Rodders

April 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCheesy Circumstances

April 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDevelopment Power

April 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1997 -

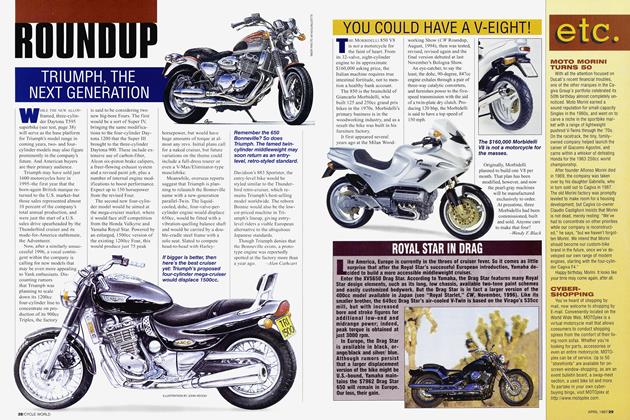

Roundup

RoundupTriumph, the Next Generation

April 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

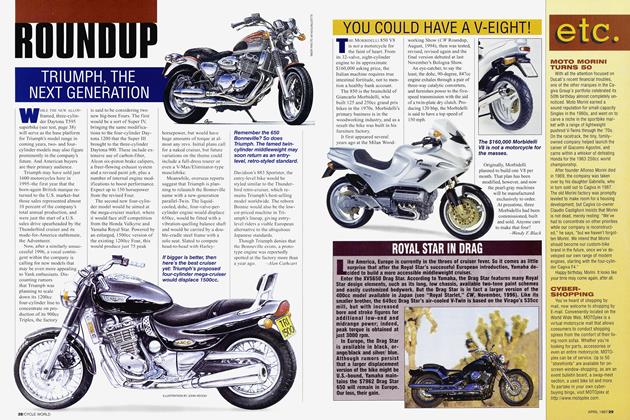

Roundup

RoundupYou Could Have A V-Eight!

April 1997 By Wendy F. Black