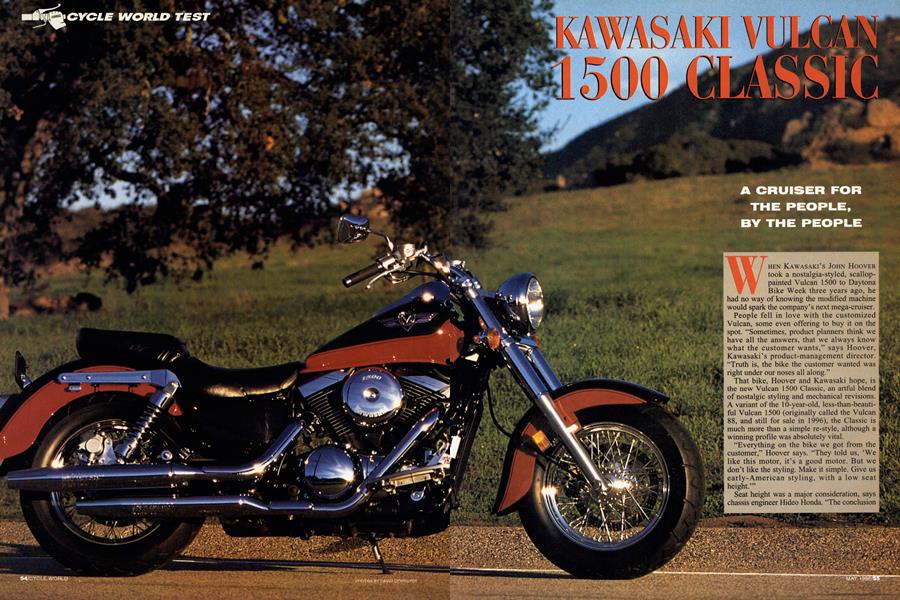

CYCLE WORLD TEST

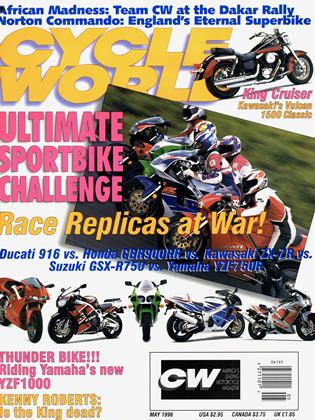

KAWASAKI VULCAN 1500 CLASSIC

A CRUISER FOR THE PEOPLE, BY THE PEOPLE

WHEN KAWASAKI'S JOHN HOOVER took a nostalgia-styled, scallop painted Vulcan 1500 to Daytona Bike Week three years ago, he

had no way of knowing the modified machine would spark the company’s next mega-cruiser.

People fell in love with the customized Vulcan, some even offering to buy it on the spot. “Sometimes, product planners think we have all the answers, that we always know what the customer wants,” says Hoover, Kawasaki’s product-management director. “Truth is, the bike the customer wanted was right under our noses all along.”

That bike, Hoover and Kawasaki hope, is the new Vulcan 1500 Classic, an artful blend of nostalgic styling and mechanical revisions. A variant of the 10-year-old, less-than-beautiful Vulcan 1500 (originally called the Vulcan 88, and still for sale in 1996), the Classic is much more than a simple re-style, although a winning profile was absolutely vital.

“Everything on the bike we got from the customer,” Hoover says. “They told us, ‘We like this motor, it’s a good motor. But we don’t like the styling. Make it simple. Give us early-American styling, with a low seat height.’”

Seat height was a major consideration, says chassis engineer Hideo Honda. “The conclusion of surveys conducted in the United States and Europe stated one common theme: The lower the seat height, the better.” “Seat height was a major thing,” concurs Hoover. But when you drop the seat height, it changes the chassis, the balance, a lot of things, so Kawasaki constructed an all-new, steel frame in which to house the Vulcan’s liquid-cooled, 50-degree V-Twin. The beefy, weldedand bolted-together

double-cradle frame, sprayed gloss black, is set off by the Classic’s deeply valanced, two-tone steel fenders,

4.2-gallon teardrop gas tank and gleaming front end. Black sidecovers complement both body and frame. The left one pops off using the ignition key, revealing space for a disc lock or a polishing cloth; opening a small trap door reveals the tool kit. The right cover is screwed in place and masks the coolant tank.

The frame is a functional platform for cruising and touring. An ultra-conservative 32 degrees of steering-head angle and 4.8 inches of trail mated with a rangy 65.4-inch wheelbase endow the Classic with rock-steady stability. Right up to its maximum speed, the bike runs straight as an arrow.

It’s a pleasant surprise, then, that the Classic reacts easily to steering inputs. This is payable, in part, to the bike’s low center of gravity and the 130-series, bias-ply Bridgestone Exedra front tire-the ultra-wide, 1-inch-diameter handlebar doesn’t hurt, either. The latter measures 33 inches tip to tip

and needs only a light nudge on the inside grip to initiate a turn or change lanes. One downside to this responsiveness is that at slower speeds-when negotiating a congested parking lot or idling through traffic, for example-steering may be a bit too light. Overall, though, it’s a very satisfying

handling package.

Fixed to the frame via a set of meaty triple-clamps is a 41mm conventional fork that delivers a claimed 5.9 inches of travel. Non-adjustable, the softly sprung assembly wears polished shrouds, Harley DuoGlide style. Leading the way is a spoked, 16-inch front wheel. A single cross-drilled brake rotor measuring 11.8 inches in diameter is squeezed

by a two-piston Tokico caliper. To accommodate various rider hand sizes, both brake and clutch levers are adjustable via four-position thumb wheels.

Considering its mission, the front end works acceptably. Fork action is on par with most cruisers-soft initially, with adequate damping control. Small roadway imperfections go largely unnoticed, but bigger hits will definitely get your attention. Similarly, the spongy front brake is powerful enough to do the job, but a second caliper-anddisc combo would be appreciated when trying to haul the 663-pound Classic down from speed quickly. Fortunately, the rear stopper-a 10.6-inch, single-piston affair-provides good power and feel.

The rear suspension is also traditional, both in its appearance and performance. Chromed shock absorbers mount to either side of the blacked-out, box-section steel swingarm and, up top, to chrome fender rails. Adjustable only for spring preload, the shocks offer a mere 3.4 inches of travel, affording the bike its low, 28.0-inch seat height. Positioned in the softest of five-available settings with a 200-pound rider aboard, the shocks compress well into their stroke, resulting in a jarring ride over all but the smoothest surfaces; even relatively minor pavement seams are transmitted directly to the rider. Increasing preload helps but doesn’t compensate for the lack of damping. Aftermarket shocks are in order here.

When it was introduced in 1987, the Vulcan 88 took VTwin motorcycle engines to new displacement levels. At 147lee, or 89.8 cubic inches, the Classic pushes small-block Chevy-size pistons through a 3.54-inch stroke via a simple, single-throw crankshaft. Each cylinder head houses four valves and a single camshaft. To partially counteract the vibration created by the narrow V-angle, a single gear-driven counterbalancer sits in front of the crankshaft. Rubber engine mounts further reduce vibration to acceptable levels, particularly at highway speeds.

Cosmetic changes, such as recast cylinder finning, modified cam-box and case covers, and a relocated induction system, were mainly intended to give the four-plug V-Twin a new look. “We turned the rear cylinder head around so both pipes exit on the same side, but other than that, it’s pretty much the same mechanically,” says Hoover.

Revised transmission ratios-the between-gear spacing from first through fourth is wider than on previous models, and fourth gear itself is very, very tall-has had an adverse effect on acceleration and roll-on performance. When CW last tested the Vulcan 1500 in a comparison in the February, 1994, issue, we noted its predilection to “lurch forward with a happy urgency only available from heavy flywheels hung on a big, long-stroke motor.” Roll-on acceleration was good, very good: Try 3.4 seconds from 40-to-60 mph and 4.0 seconds from 60-to-80 mph. And in the standing quarter-mile, the old Vulcan raced through the lights in 13.39 seconds. Top speed was 109 mph.

In comparison, the re-geared Vulcan Classic doesn’t accelerate as briskly as its predecessor. Roll-on acceleration from 40-to-60 mph and 60-to-80 mph takes 1.2 and 2.9 seconds longer, the quarter-mile takes 1.21 seconds longer, and top speed is down by 5 mph.

What gives? Well, Kawasaki claims a stump-pulling 90 foot-pounds of torque at the output shaft, but the CW rearwheel dynamometer did not concur; there, the 1500 produced 47 horsepower and just 66.5 foot-pounds of torque. That’s down considerably from the 56 horsepower and 78 foot-pounds of torque our last Vulcan 1500 produced.

Unlike the original Vulcan, which has its keyed ignition mounted just forward of the right sidepanel, the Classic’s ignition is located on the left side, just below the gas tank and in front of the leading cylinder. To see it from the saddle, you have to lean to the left and crane your neck a bit—it’s even more awkward to actually insert or remove the key. Cold starts require full choke, which can be thumbed off completely within a couple of minutes.

At idle, the big V-Twin sounds as if it graduated summa cum laude from the School of Aural Delights. Though muted, it’s an appealing, almost mesmerizing, sound-a sort of piston-and-valvetrain concerto. Twist the throttle, and the sound travels downstream, spilling sweetly-if a little too quietly-from the dual mufflers. The chrome exhaust system is more than the simple, 2-into-2 setup that it appears to be. There’s a large, blacked-out pre-muffler housed below the swingarm. inboard of the headpipes.

The Classic’s best feature may be its ergonomics. The handlebar is a comfortable reach, angling the rider slightly forward into the oncoming windblast. Equally well placed, the floorboards are almost parallel to your thighs, placing knees in a comfortable, near 90-degree bend. Mildly dished, the seat is well padded, but “hot spots” develop toward the end of a tank of gas. Overall, though, a pretty decent riding position.

It’s no surprise, then, that Kawasaki is also considering a touring model based on the Classic. “The base unit is capable of touring right now, but there are some items-like saddlebags and a windscreen-that make it a better tourer,” says Hoover. “The progression toward an even more touring-oriented application is a. natural transition. I don’t think you invest this kind of money and sit back and say, ‘Well, that’s it. That’s the only one we’re going to make.’ You’ll see some other things coming in the future.”

The million-dollar question, of course, is, “How much does it cost?” The Vulcan 1500 Classic will retail for $10,499. That’s $2000 less than Honda’s Valkyrie and a whopping $3000 under Yamaha’s Royal Star. “We were fortunate that we could price the bike at $10,500 and still maintain a good margin,” says Hoover. “We think it’s a good buy.”

Kawasaki is hoping that for cruiser customers, that’s a message heard loud and clear. U

VULCAN 1500 CLASSIC

$10,499